In part two of our our interview, RIBA president Muyiwa Oki explains why he wants to refocus architectural education on to a reuse agenda.

What is the purpose of architecture and what is the architect’s role in society? These are fundamental questions that each generation has to ask afresh.

RIBA president Muyiwa Oki was elected on a platform calling for a radical rethink of how we design and build. He wants the profession to help find solutions to the climate emergency, and to put a greater emphasis on how it serves ordinary communities across the UK.

“What I would like to see is every architect seeing themselves as an advocate for change,” says Oki. And he believes that a key focus for this new agenda must be the creative reuse of existing buildings.

He sees reuse as not only essential to reducing carbon emissions, but also as an effective way to engage society, and particularly young people, in a wider debate about the built environment. “What I would like to focus on is that public conversation around how architecture solves issues,” he says.

“I want the profession to help tell that story about how retrofit and reuse can have a positive impact on people’s lives, in terms of quality of place, energy demand and sustainability. That’s what motivates me – communicating what the value of architecture is.”

Oki also argues that good architecture is not something that should just be enjoyed by the affluent. And, because of the way it connects to the skills agenda, and efforts to support disadvantaged communities, he believes reuse offers the perfect narrative around which to communicate his wider message.

The first months in any leadership role provide an unparalleled opportunity to set the agenda and make an impact. That’s why Oki has organised a reuse panel discussion with The Prince’s Foundation on 20 September in Fleetwood, Lancashire.

“This idea is multipronged. It needs to permeate the national conversation”

The collaboration with The Prince’s Foundation is the outcome of what he describes as “a serendipitous moment of connection”, arising from a meeting with the organisation’s deputy director, Sarah Robinson. For Oki, the link-up was about identifying the most suitable collaborator to work on with the reuse agenda. “For me, it is all about how to push forward the idea that design should care about everyday life and everyday issues, and reaching out to different constituencies who are involved in that space. And The Prince’s Foundation has the existing relationships and shared agenda that can help us do that.”

>>See also: ‘I don’t seek permission, I ask for forgiveness’ – Muyiwa Oki on his plans for his RIBA presidency

With his emphasis on the power of storytelling, Oki was also impressed by the range of advocates that The Prince’s Foundation works with – what he calls “voices of the people who can speak the language of design to the public”. Among these voices is that of the architect and presenter George Clarke, who will be attending the first town hall along with key local stakeholders.

“This idea is multi-pronged. It needs to permeate the national conversation,” says Oki. “People like George Clarke need to talk about reuse and put it on their shows. We need to excite people.”

The meeting in Fleetwood will be centred on the coastal Lancashire town’s former hospital. What started in the 19th century as a cottage hospital grew over time into a large institution, including a three-storey block that was built in the 1980s. The NHS largely vacated the building in 2009. Since then, it has been mostly empty, standing as a forlorn reminder of the area’s declining fortunes.

In 2018 the Fleetwood Trust was created with the express purpose of buying the site and finding a new community use for the buildings. Twelve locally connected trustees, each with their own areas of specialist expertise, oversee the charity.

The purchase went through in the winter of 2018. Since then, The Prince’s Foundation has been advising the trust and helped to win planning for a new community hub, to include local services, education spaces and a café.

What is most striking about the building is that it is not a typical at-risk heritage asset, but a very ordinary redundant public building, of which there are thousands across the country. For Oki and The Prince’s Foundation, it is the ordinariness that makes the Fleetwood project important.

Rather than just working exclusively on glamorous new-builds, or high-value commercial retrofit schemes, Oki and Robinson believe that the next generation of architects will need to start addressing the ordinary underutilised buildings that surround us everywhere.

Fleetwood

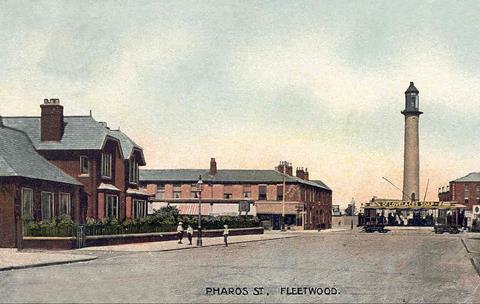

Modern Fleetwood is the creation of Sir Peter Hesketh, a 19th-century landowner and developer. His vision was for a Victorian coastal town with a railway connection. He entrusted the renowned architect Decimus Burton to design a new town layout and some of its key buildings.

Fleetwood thrived as a bustling coastal centre, serving as both a transportation nexus, with ferries to the Isle of Man, and a popular seaside getaway, while also establishing itself as a prominent fishing port.

From its inception in 1831 until the 1970s, Fleetwood provided ample employment opportunities. However, over the past five decades, it has faced a steady decline.

This decline can be attributed to the closure of the railway station in the 1960s, the shuttering of the ICI plant, the decline of the fishing industry and the closure of the port, as well as the discontinuation of Isle of Man ferry crossings.

As a result, many areas within Fleetwood have experienced significant economic hardship. Notably, the immediate vicinity of Fleetwood Hospital ranks amongst the top 5% most-deprived areas in the UK.

Oki’s interest in this type of work goes back to his university days, studying in Sheffield. “I was very inspired by Lacaton & Vassal. I think I got the idea of deep retrofit from reading about their work.”

He references the practice’s social housing scheme in Bordeaux, where new balconies and outdoor space were added to an unprepossessing mid-century slab block. “Their style of architecture, it’s very forensic,” says Oki. “There is an elegance of style and economy and it’s kind of true and rough and ready.”

His time studying in Sheffield, and later working in Birmingham for Glenn Howells Architects, also helped to give him a perspective on life outside the capital that has significantly contributed to his world view. He talks of how the course in Sheffield prioritised community engagement, and how this exposed him to the needs and challenges faced by everyday communities.

“The teaching in Sheffield was always focused on human scale, community engagement and participatory learning. It really does get you up close with your community – the community that you study and live in,” he says of his time at university. “You really understand the depths of deprivation that exist and how people’s hands are tied.”

He believes that small architectural interventions can have an outsized impact on how communities perceive themselves – and are seen by others. “Just little interventions change outlooks,” he says.

“It was one of the key things I learnt. It’s just about showing up in different spaces and creating a buzz. Architects and the community can create something to look forward to in that area and then you hope that other people will feel that way too and follow suit.”

But, if Oki is a believer in the power of small-scale and local action, he is not losing sight of the systemic challenges communities face or the wider national and international context. He wants to challenge the way in which many architects aspire to work on what are often seen as more glamorous new-build projects.

“The profession needs a mindset shift in terms of what we do as practices,” he says. “What I want to do is bring reuse projects to the same level as new-build, so they have the same innovation and quality of design attached to them. I think, if we can do that, we will have a richer, more vibrant body of work.”

Another key objective of Oki’s campaign is to spread this same message to regional universities and schools of architecture. Oki’s own experience at Sheffield was of being encouraged to design new-build schemes, rather than think about reuse.

“Addressing reuse and energy demand is one of the biggest challenges facing the UK. We need to start using our creativity and research, housed in our universities, to help bridge the gap in policy,” he says.

“We need to start thinking about architectural education as actually helping solve some of the key issues facing the country. We want to get our universities to think about this work, so the next generation are advocates for reuse.”

As part of his drive to improve diversity and access to the profession, he also wants reuse to act as gateway to becoming an architect. “I hope that it excites young people and gets them to see that the profession is solving issues that they care about.

“One of the main issues that concerns the next generation is how we’re going to solve the climate emergency – and a career in architecture is one way that you can go about doing that.”

Oki believes new-build will still have an important role to play, but says: “It’s not that we shouldn’t do any new-builds anymore, just that we should consider reuse before we go for new-build. I think the conversation is starting up and down the country.”

And he is keen to make the case for reuse opening up new possibilities for the profession and individual architects. “It’s about the expansiveness of architectural practice,” he says.

“We all need to be able to chart a path that makes sense to us, but also come together on this commitment to ensure that architecture demonstrates that it cares about people and everyday issues.”

At this initial event at the former hospital building in Fleetwood, Oki wants to spark a discussion about the benefits of investment in underutilised buildings and “move the dial forward” on the national reuse agenda. “I think architects need to take ownership of this and move forward as a profession. At the crux of it is how the built environment shapes our lives.”

The Prince’s Foundation

Sarah Robinson is the associate director (UK) for architecture and heritage at The Prince’s Foundation, which she describes as “a placemaking and education charity”. Acknowledging what has sometimes been a strained relationship between their own President (Charles III) and the RIBA, Robinson believes that since the coronation there has been a growing appreciation of the common ground that exists between the King and most architects.

“I think a lot of architects are realising that they have more in common with him than they have differences, particularly around the value of community and sustainability in its broadest sense,” she says.

Robinson is keen to stress the urgency of the climate crisis and highlights that the speed at which society must deliver reuse projects necessitates a pragmatic and proactive way of working. She sees Fleetwood as an exemplar of this approach, and hopes the forthcoming event will help ignite a wider discussion about these issues.

Although the RIBA and the former Prince of Wales have not always seen eye to eye, it is easy to see how Muyiwa Oki has found common ground with The Prince’s Foundation and Robinson’s team. “I think in terms of Muyiwa the inclusivity, openness and access to education in architecture is a really key thing that has enabled this partnership with the Foundation,” she observes.

Robinson also believes that the organisation’s focus on traditional construction skills is a natural fit with the reuse agenda. “People often think craft skills are just about conservation”, she says.

“My view is that local craftspeople have the inherent knowledge of natural local materials and building typologies that is actually what we need to help us reuse many buildings.”

There is also clearly common ground around a commitment to grassroots action and community engagement. “I think in terms of the alignment with Muyiwa’s principles, we are also thinking about community-driven action, local skills and engendering a sense of getting people interested in architecture. I think they are really the key things for us that we wanted to address together.”

Robinson says the organisation very often gets involved in projects like Fleetwood at an early stage and then helps with small amounts of seed funding that can be used to help write a business plan or submit funding applications. She sees the project to turn Fleetwood’s former hospital into a community hub as typical of the challenges faced by many communities.

“I think a building like Fleetwood is what a lot of people are struggling with – older civic buildings that don’t necessarily tick the box for heritage or arts council funding can be found in towns across the country.”

The ward in which Fleetwood Hospital sits is amongst the top 5% of most deprived areas in the UK, but the proximity of adjacent more affluent areas mean that it has not qualified for levelling up funding. Robinson says the community has a great attachment to the building because many people were either born or treated there. “This site has huge social and embodied carbon significance. For the community it’s a focal point.”

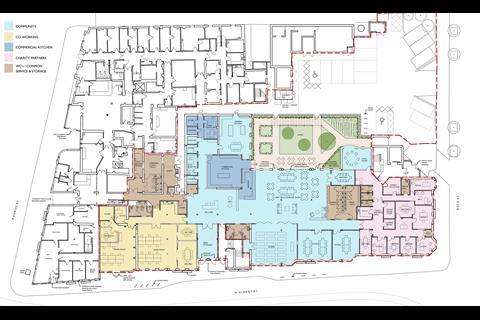

A small part of the building has been leased back to the NHS for outpatient services and the remainder is going to become a mixed-use community hub. When finished it will include a youth club, an outpost of Blackpool and The Fylde College, a launderette, clothes exchange, Macmillan Cancer Support centre, foodbank, community café, counselling and support spaces, and offices for a housing association. “We’re working with the local trust to do what we can when we’ve got the money,” says Robinson.

The Prince’s Foundation’s support to date includes providing architectural services up to planning and acting as post-planning client adviser. As a key aim of the project is to build local capacity, the next stage of the design work has been handed over to an architect from nearby Lancaster, Lee Donner of Mason Gillibrand.

The event on 20 September has been designed to “link with regional architecture schools and get them into the audience”, she says. The head of Manchester School of Architecture, Kevin Singh, is expected to attend along with some of his students, plus students from Lancaster University and Oxford Brookes.

Robinson is herself an associate lecturer at Oxford Brookes, where she recently invited her students to come up with their own proposals for the Fleetwood Hospital site. The students visited Fleetwood, met stakeholders and came up with what Robinson describes as “14 really cracking proposals”. Their designs will be on display during the townhall meeting on 20 September.

“It comes back to education,” says Robinson. “I think so many more of our architectural schools should be teaching this as a central part of their curriculum, because those students are going to have to come out and deal with these types of buildings.”

Like Oki, she believes that working on reuse projects offers a lot of professional rewards for those who approach them in the right way. “Just because you’re working within a lot of constraints doesn’t mean it’s not going to be an interesting challenge with a beautiful outcome,” she says.

>> Also read: All architects need to be agents of change

>> Also read: Muyiwa Oki on his plans for his RIBA presidency

No comments yet