District heating could hold the key for greening the UK’s existing homes. So why, when the technology exists and is used throughout Europe, do we still rely on individual systems?

The Scandinavians have long led the way in low-energy building design. They licked the problem of airtightness and thermal insulation years ago. Triple glazing is de rigueur and energy performance certificates were quick to take off.

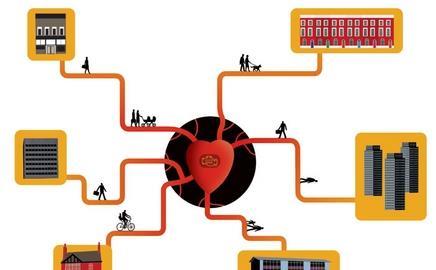

They have also been trailblazers in district heating. These are the systems that deliver waste heat from power stations or central combined heat and power (CHP) plants to buildings via a network of pipes buried in the ground. Compared with individual boilers in homes, this can be a lot more efficient as the heat produced when generating electricity can be made use of rather than being wasted through a cooling tower. Carbon savings can also be made when biomass is used or the district heating displaces more carbon-intensive electrical heating.

This, however, could be about to change. First, the government’s gradual unveiling of its definition for zero carbon, which will apply to all new houses by 2016, includes plans to offset further carbon emissions using on- and off-site solutions. One of the main off-site solutions is district heating.

Second, and perhaps more significantly, district heating might also hold the key for greening the existing housing stock. The main political parties have been making a lot of noise about how they plan to cut carbon emissions from the UK’s 25 million plus existing homes. There are proposals for making loans available so householders can improve their home’s insulation, for example. The problem with this, though, is that some homes are easier to improve than others and costs can rise rapidly for increasingly small improvements. A smarter way may be to make the changes that are most cost-effective and then simply plug the home into a low-carbon heat source – like district heating.

According to Phil Jones, energy consultant at Building Energy Solutions, who also chairs CIBSE’s combined heat and power group, the problem with existing housing stock is really heating. “You get to a point where making fabric improvements to the building becomes prohibitively expensive – either that or you live in a conservation area or a listed building where it’s often not possible to carry out the necessary changes. One of the solutions is just to supply low-carbon heat from a central source.”

Alasdair Young, senior engineer with Buro Happold, agrees that it’s one of a number of solutions but says district heating is only suitable where there is a high density of housing. “What you want to do is to try and limit the length of the network for the given amount of heat you are supplying.”

This is partly to reduce costs – the pipe network accounts for up to two-thirds of the price of the system. “It needs a higher density of housing such as a city centre, where it can also benefit from a mix of building types.” Having offices, schools and homes connected to the same network evens out the demand profile and provides a constant base load.

Such hurdles hardly explain why district heating has made such a small impression in the UK. Young says there is a stigma associated with badly installed systems from the sixties, which were poorly designed and maintained. This has led to a fear that tenants and homeowners will be unwilling to accept such systems.

However, a survey conducted by the UK Green Building Council in November last year revealed strong public support for “green utilities”, with 71% believing that a district heating system could be better than the current individual systems in their homes.

It needs a higher density of housing such as a city centre, where it can also benefit from a mix of building types

Alasdair Young, Buro Happold

The technology has also improved since the sixties, says Jones. “The latest plastic twin wall piping is extremely effective, with temperature drops of only 1ÞC/km, and the prices are coming down.” It’s not insurmountable, he says, but it needs the right incentives and organisations to pull it all together.

However, Jones adds, in the UK we do not seem particularly adept when it comes to digging up the roads and putting in new infrastructure, which would be needed to install the pipework. On top of this are the practicalities of taking supplies into homes, installing the metering and modifying or upgrading the home’s existing central heating so it can run off a district system.

Last October, the London Development Agency (LDA) published a prospectus to support the expansion of a decentralised energy market in the capital. The aim is to deliver 25% of energy from local sources by 2025, which it is claimed would cut 3.5 million tonnes of CO2 a year. Major decentralised energy projects are emerging across the capital, including the Elephant and Castle regeneration and the Thames Gateway heat network. London mayor Boris Johnson is encouraging boroughs to identify potential networks with the help of a new interactive heat map, which helps in assessing the feasibility of district heating by showing the heat load in any given area.

One of the critical things with any proposal is finding a building, or buildings, to anchor the scheme. “Often you can find a big block of flats run by a local authority and then you find these things have a life of their own and grow like tree roots,” says Jones. “The Pimlico District Heating Undertaking, the oldest district heating system in the UK, was set up in the fifties and has grown to supply over 3,000 homes and 46 commercial properties.”

The tricky bit is the funding. According to Young, who worked on the LDA plan, research shows that up to 14% of UK heat could be supplied from district heating but, with the economic incentives currently in place, it is likely to be considerably less than 1%. “These are infrastructure systems. They take a long time to plan and build out, so it is difficult to get private financing for them, but if you get government or local authority backing, you can get private investors interested”. This is the idea behind the London Green Fund, a £4m package launched by the Greater London Authority last year to kickstart eco innovation.

Currently, district heating systems are mostly being pushed through new build by planning policy. “This means you don’t get the benefits of scale – the savings of say a couple of hundred dwellings aren’t that great,” says Young. But a network to pick up large chunks of existing housing? That could be a different matter.

Next week: In the final part of our series on tackling existing homes, we take a look at how the energy use of one Victorian house has been slashed by 80%

Original print headline - The heart of the community

No comments yet