Speed is everything in construction today, so concrete specialist John Doyle has devised a system that means the building core can be built at the rate of a floor a day. Thomas Lane found out more

Anyone who can come up with a way of constructing office buildings faster in the current market is going to be in demand. Developers are desperate to get their schemes finished and tenants in before the market dries up completely. Even in better times, quick delivery is a good thing because it means the money starts coming in earlier. The question is, how do you build faster? After all, smart contractors have already got office construction down to a fine art.

A good place to start is the building core, because it’s here that improvements in speed and quality can make a real difference. “It absolutely sets the pace of the project,” says Gareth Lewis, construction group board director at Mace. “It’s fundamentally important to get it right and get it up as quickly as possible, because it dictates the steel frame, which in turn dictates the cladding, which dictates the M&E and so on.”

Because of this, lots of time and energy have been expended on finding ways of building cores more quickly. One such technique is automatic self-climbing formwork, a system that is operated hydraulically rather than with a crane. More recently Corus devised the Corefast system, which involves prefabricated steel sandwich panels being filled with concrete after final positioning. Now, concrete specialist John Doyle Construction has developed a system it says is faster to construct, safer to build and is of better quality than insitu construction. It certainly impressed Lewis and the client enough to use it on a Mace project at 3 More London near Tower Bridge.

They may be elements that are completely covered up by the end of the project, but getting the core plumb straight and the interfaces with the steel frame in the right place is crucial. The interfaces are called “embed plates” which are large steel plates weighing half a tonne that have to be tied into the rebar of the core, then the concrete cast around these. Getting these in the right place is time-consuming and difficult. If the plates end up in the wrong place, it means lots of extra work for the steelwork specialist. “Quality is important as the last thing we want is to rework the floors,” says Lewis.

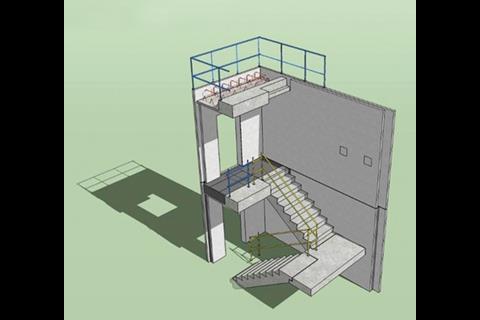

So how does the Doyle system speed up the well-honed process of office construction? Well, insitu concrete cores are built using either the slipform or jumpform method. Both are similar in that the formwork is placed at the top of the core, and the core walls are cast. The formwork is then moved up another level and the process is repeated all the way to the top. Once the main structure is up, the stairs and landings can go in.

Eric Roberts, John Doyle’s construction director at the More London job, says the fact contractors have to wait until the core is completed to get on with other work is what slows the project down. “The core is covered with formwork so you can’t get access to the inside easily,” he says. This means the crane can’t drop the stairs and landings in until the core structure is finished. The steelworkers want to get on with the frame too, but again limited access slows work down. If they work off cherry pickers, these get in the way of the substructure works and is also dangerous.

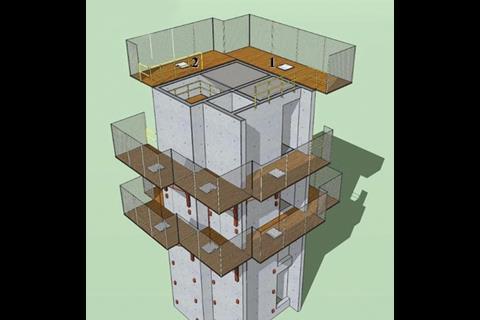

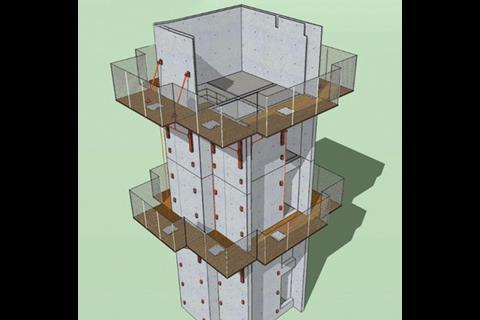

Doyle’s solution is to build the core from prefabricated panels. As with the Corus Corefast system, two panels are separated by a gap and are filled with concrete when positioned. The difference is that these panels, called “twin wall”, are made from concrete, and come complete with rebar in the middle which means they are cheaper than all-steel panels – Roberts says the Doyle system costs the same as traditional, insitu concrete construction.

The core sets the pace of the project. It’s important to get it right and get it up as quickly as possible, because it dictates the steel frame, cladding, the M&E and so on

Gareth Lewis, Mace

Another advantage is that the core walls, stairs and landings can all be built in one go at each level, with no formwork. Once the twin wall panels are in position, self-compacting concrete is poured into the gap. A prefabricated bottom landing and stairs are installed and the top landing cast with insitu concrete. The embed plates are fitted in the factory so these are in exactly the right place, making life much easier for the steel work team.

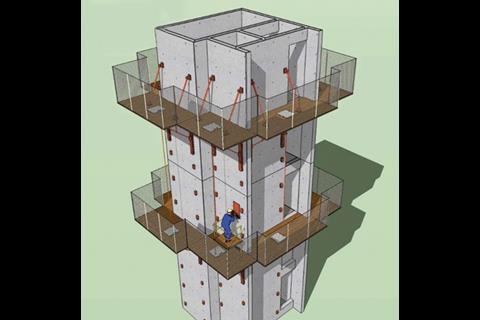

Having the stairs and landings in place also helps the steelworkers. A simple platform is all that is needed to build the core and this can be left in place as the core progresses so steelworkers can easily and safely weld the connecting plates for the frame to the embed plates. “Because we are putting the stairs and landings in as we go and we leave the working platform in place, we can give the welders really safe, fast access,” says Roberts.

Peter Emerson, the chief operations officer of steel specialist Severfield Reeve, who is doing the steel frame at More London, says: “In our opinion the cores are as good as we have ever seen. They are both plumb and there is no significant degree of twist, which is important to us as we have to connect our steel to them,” he says. “It makes the steelwork much more efficient as it has accurate, reliable connections with factory standards of quality.”

For John Doyle’s Roberts the More London job is the culmination of five years’ work. The firm initially used twin wall for basement and general structural wall construction, before trying it for core construction. The first standalone cores built with twin wall was at a Bovis Lend Lease job for developer Stanhope.

“They weren’t a blinding success but adequate,” says Roberts. “They were accurate, but hard work.” At More London Roberts felt he was getting into his stride. “With the last seven floors we’ve achieved a floor every day. That includes the stairs, the landings, embed plates, the lot. It’s never been done before.”

Roberts says the system is ideal for buildings up to 18 storeys high, as the maximum panel thickness of 450mm limits the system’s height. He says it is particularly suited to awkward situations such as building up against a party wall. Contractors like the system for its speed, quality – including surface finish – and safety, and Roberts says the firm is already getting lots of enquires, and that is particularly good news in today’s economic climate.

No comments yet