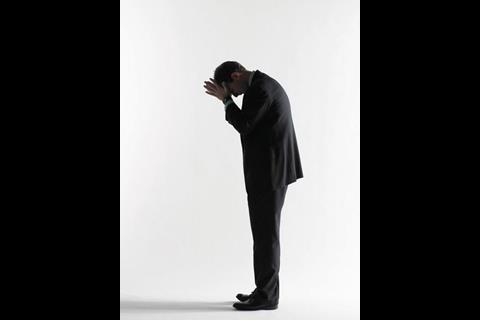

The financial damage suffered by the industry is reflected in the emotional damage suffered by its workers. But big boys don’t cry, and they don’t seek help when they need it

Mark had been in the construction industry for 18 years when he was made redundant from his job as a senior executive in September.

But nothing in that time had prepared him for what was to follow. “As a senior executive in a major construction firm, you think you have a pretty good idea of what’s going on,” he says. “You don’t. I was devastated. I had been in the industry since I left university, and worked my way up to a position I was proud of. I’m in my 40s, responsible for incredibly large contracts and suddenly I’m just put to one side; thrown on the scrap heap.”

The emotional toll of redundancy soon began to take its toll on Mark’s personal life, causing him to argue with his family more and more bitterly as his sense of self-worth plummeted. “I was argumentative, erratic, deflated. I was at a loss. I was stuck in a mindset of depression and a never-ending black-hole. I was in a spiral, and I was going further down.”

In the end, Mark contacted a counsellor, and it was that decision that saved him. He pulled his life around and got a top post in another construction business. But his is one story among many. There were 48,000 redundancies in the past quarter alone, and countless more executives and workers are living in fear that they may be next. At the same time, site workers in particular are coping with the increasingly pressurised work practices of the modern industry. As a result, the problem of emotional stress is hitting the industry harder than ever before. Here we examine the scale of a problem often hidden behind construction’s macho image, and look at what can be done to to stop its destructive impact.

The hidden problem

The impact of recession on the mental health of the construction industry’s staff at every level is dramatised by the rise in the number of suicides in the early nineties recession. Figures from the Office of National Statistics show that between 1982 and 1987, 157 building and civil engineering manual workers committed suicide; this rose to 183 in the period from 1991 to 1996, as the recession took its toll. The problem also grew at the professional level: 24 managers in building and contracting took their own lives between 1991 and 1996, up from 18 between 1982 and 1987.

Mental health charities are now warning that, unless enough help is made available to those who need it, the problem will get worse in this recession. Mind says it has seen a 60% increase in calls to its MindinfoLine about money issues from callers struggling with the impact of the recession. American psychologists this month coined the phrase, “econocide” to describe a growing trend of suicides they say are linked to the global economic crisis.

There have also been two high-profile cases of managerial suicides linked to the construction sector this year – Adolf Merckle, a billionaire who owned large parts of HeidelbergCement, was “broken” by the financial crisis after losing £1bn in the downturn. Two weeks later, millionaire Irish property mogul Patrick Rocca was found dead in a suspected suicide after the downturn lost him a fortune as well.

Why is it happening?

Paul Farmer, chief executive of Mind, says a big risk factor for suicide in the current economic climate is simply being a man, as one in seven of them develop depression within six months of losing their job. “The construction industry, which has an 85% male workforce, has been hard hit by the recession, making its workers more at risk than most,” he adds.

For site workers, there are added pressures. Between 2001 and 2005, 979 men involved in construction trades committed suicide, according to the British Journal of Psychiatry. Although no comparative data was available for earlier years, this number is higher than would be expected from national trends (the sector has a proportional mortality rate of 103, compared with the benchmark of 100) and means that the sector is one of the highest 10 groups affected by suicide in the UK.

Steve Acheson, a Unite branch official, has been in the industry for 40 years. He blames the rise in suicides in part on the continual drive for projects to be completed quickly.

“Everything is about time,” he says. “The men are being pushed and pushed to get the work done in record time. Twelve-month schemes are now done in five months. You can see the stress this causes on site with project managers ranting and raving, and workers losing their morale. Lunch breaks used to be a laugh. We were often friends with the project manager and you’d end the day in the pub with them. Now, workers are frightened of employers because they feel bullied by them.”

Acheson adds that the increased use of labour agencies, under which workers are employed on a temporary basis on any given site, means relationships are harder to form. “There’s a casualisation of labour now. Ten years ago, you would have had 50 electricians on a job from start to finish. Now you might see 700 passing through.” Working for an agency can also mean a worker is not entitled to paid holiday because they are classed as “self-employed”. Acheson says he knows several men who will not take holiday as a result, and sometimes work 365 days a year.

His colleagues, says Acheson, are all stressed, worried by the financial climate and lack of jobs, and are prone to mood swings. But he doesn’t believe any of them will seek professional help. “We’ve all had sleepless nights worrying about getting work in this climate, and being able to support our families. But we’re stubborn,” he says, “we won’t seek help.”

This desire to maintain a macho facade is one reason why mental health experts fear men are most at risk. Farmer says: “The image of the tough male who doesn’t show emotion is so widespread that often men are unwilling to seek support.” One in three men say they would be embarrassed to see a GP about feelings of depression. As Celia Richardson, from the Mental Health Foundation, says: “The big thing for men is asking for help.” Acheson adds: “As the man of the family, and the breadwinner, being out of work makes you feel like you’ve failed your family. It can be a huge burden to carry.” Mark felt this pressure when he lost his job. “People fail to understand that, when you’re made redundant, it involves your family too,” he says. “They suffered terribly.”

What can be done?

The government is clearly worried: in March, the Department of Health announced that it was investing £13m in a series of packages to help unemployed people experiencing depression. Measures include a credit crunch phone line, run by NHS Direct, with health advisers trained to spot people who might be experiencing depression as a result of the recession.

Psychological help is also being offered, with the government advancing its roll-out of talking therapy services across the country in 2009. Annual funding for these services will have risen to £173m by 2010-11, and 3,600 extra therapists will be trained in order to treat 900,000 more people over three years.

Several construction firms have taken matters into their own hands and have sought the help of a counsellor to help staff cope with redundancies and financial difficulties in the downturn. Counsellors have already noted a huge rise in the number of concerned firms seeking advice on employees’ mental health. Corporate psychologist Kathy Curnan, the counsellor who treated Mark, says the numbers of enquiries she has received from this sector is “unprecedented”.

Contractor BAM has also been trialling drop-in nurse visits at two of its sites: Newcastle-under-Lyme College, and Mann Island, Liverpool. Workers seem to be taking advantage of these services, albeit slowly. The occupational nurse at the Mann Island development says there has been a rise in drop-in visits in recent months, with more signs of stress and anxiety as well as more requests for general advice.

But will it work? Cunan believes therapy can definitely help people cope with the uncertainty after losing their job. “It’s about re-conditioning the mind,” she says. “When a person has made redundant they can feel like they’ve lost control. It’s about showing them how to regain that control.” Mark would certainly recommend seeking professional help, and admits he doesn’t know what would have happened to him if he hadn’t had counselling.

“It gave me my confidence back; made me look at life in a totally new light, which enabled me to apply for jobs and be taken seriously on the job market.

“I can truthfully say, if I hadn’t received therapy, I wouldn’t be in the fortunate position I am in now.” That position is a more senior role than his previous job.

“I was absolutely devastated when this happened, the whole family were,” he says. “Now I’m in an even better position. I feel like luck has shone on me. I’m not sure it would have done if I hadn’t sought the help I so desperately needed.”

Mark’s name has been changed at his request.

Original print headline - Stress relief: The story of one man who almost left it too late

The warning signs

Mark says that, after losing his job, he became argumentative, and suffered from anxiety attacks, symptoms that Celia Richardson of the Mental Health Foundation says are the first warning signs of depression. “Everyone is bound to feel down if they’ve been made redundant. But when this state of mind continues for weeks on end, it becomes worrying,” she says.

Other key indicators include a change in eating and sleeping habits, loss of libido and an inability to concentrate.

“You may feel devastated,” Richardson says. “People often take redundancy very personally, and it can erode one’s self esteem, but you should remember, in a global recession, there are countless others going through the same thing. And there is help out there.”

Postscript

The “Get if off your chest for Mind” week, aimed directly at men, runs from 9 May: www.mind.org.uk

You can contact the MindinfoLine on 0845-766 0163

Topics

Survival Special

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

Stress relief: coping with the psychological impact of recession

No comments yet