This is the story of a man who gave a TrustMark-registered firm £22k to renovate his home. What he got for his money was two weeks’ worth of work, three years of hell and a wrecked house. But how did the builder keep its reassuring logo?

Even before Kevin Arrowsmith opens the front door of his house, it’s clear that something is badly wrong. He’s fumbling to put his key in the lock while shielding his eyes from the springtime Portsmouth sun. As he curses, I glance upwards and see why: the light is shining through a hole in the masonry. Arrowsmith shudders. “I hate this house. But this is nothing – wait until you see inside.”

We are at 184 Landguard Road, the address that should have been Arrowsmith’s home for the past three years. That was before a six-week renovation, begun in September 2006, turned into what Arrowsmith describes as a “living hell”. After spending five months in the house, Arrowsmith’s builders, Southampton-based Keystone Construction UK Ltd, were paid about £22,000, which Arrowsmith says was the price reached in the initial verbal agreement. In return, he received a wreck. The builders also took fittings that Arrowsmith had paid for, and as a finishing touch demanded more money for variations and extras.

So far, we have a familiar tale of the damage that cowboy tradesmen do to their customers’ financial and emotional wellbeing. Except that Arrowsmith’s builders weren’t cowboys: they were TrustMark-approved.

A brief history lesson

The TrustMark story begins in April 2000, when the government launched a different scheme: Quality Mark. This was the brainchild of Nick Raynsford, the then construction minister, and it quickly became the government’s main effort against rogue builders. Four years later, £10m of taxpayers’ money and much ministerial time had been spent on the scheme – and so few firms had signed up that the cost worked out at exactly £17,000 for each. After a period in denial, the government admitted defeat in 2004.

The following June, TrustMark was born. The DTI’s strategy was to bring existing accreditation schemes under one brand. It would have its own board, but would be operated by about 26 “scheme operators”: these were trade bodies, certification providers and commercial organisations; they handled accreditation and complaints. What they were looking for, in the words of a householder in a supplement published in 2005, were builders who “arrive at 7.30am every morning, make their own coffee and tea and don’t call me ‘love’”.

The main advantage of this plan for the DTI was that it couldn’t fail: firms that were part of existing schemes joined automatically, and others found it almost as easy to become members. Whereas Quality Mark required a financial audit and a day-long inspection, TrustMark required registered firms to meet relatively relaxed “core criteria”. So in place of an audit, there was a credit check and a search for county court judgments.

Then there was the cost: membership of Quality Mark was £500 a year for a £100,000-turnover firm, and required contractors to provide customers with a six-year insurance-backed warranty. TrustMark was pretty much free.

All of which raises the question of just how much of a guarantee TrustMark provides. The organisation says only a minuscule number of cases are unresolved (see TrustMark’s response below). But in this instance it took Arrowsmith 18 months, hundreds of letters and hours of phone calls to receive an offer of remedial work from the scheme operator that approved Keystone – but that was worth only a fraction of what was needed to rectify the damage and admitted no liability. What is clear to Arrowsmith is that the TrustMark system failed to provide him with a remedy.

And it may not just have been Arrowsmith who suffered. Despite the fact that TrustMark was aware that Keystone had turned 184 Landguard Road into a house of horror, it continued to endorse it as an approved trading company. It also indicated that it was in financial health for months after it had entered into an insolvency agreement. TrustMark did not break its own rules by doing this, as despite prominently advertising “checks on financial status” as a key benefit of using a TrustMark firm, the smallprint on its website says financial checks are made by scheme operators when vetting firms for membership, and may not be monitored continually.

Arrowsmith’s story

In the summer of 2006 Arrowsmith inherited £24,000. At the time he was 36 years old and living with his father, so he decided to use the money to renovate a house he owned in Landguard Road, after which he would move in with his girlfriend.

Arrowsmith’s nightmare began at a local networking event – he owns a signage business, and had gone to meet other local businessmen. Among them were some directors of Keystone Construction, and Arrowsmith was impressed enough by their credentials to ask them for a quote. “My father had been saying we should get local lads we knew to do it, but I said no because I wanted the whole lot done and I didn’t have time to watch over it. They were promoting themselves as good because they were registered with schemes like TrustMark and Corgi, so I said I’d get them to do it.”

Arrowsmith says Keystone quoted £22,000 for the complete renovation of the property. The job, it said, would take five to six weeks. Work started in late September, but after a month, Arrowsmith realised there were problems. “I knew it was going slow, but I was paying in instalments so I’d already given them a lot of money.”

The parties extended the deadline until Christmas, but by the second week of January, the house was still unfinished. Arrowsmith called Keystone’s three directors to a meeting in the house. “I said it wasn’t good enough, and they started shouting and calling me effing picky, saying they thought I was a mate. I said I wasn’t going to be intimidated in my own home, but to be honest I was frightened – they’re big blokes.”

Arrowsmith decided against taking legal action (“They had my money, so I didn’t want to go too heavy”) in favour of just hoping the work would get finished. On 9 February, he received a phone call from one of the directors, saying it was done. “I opened the door. And what I saw is what you see now.”

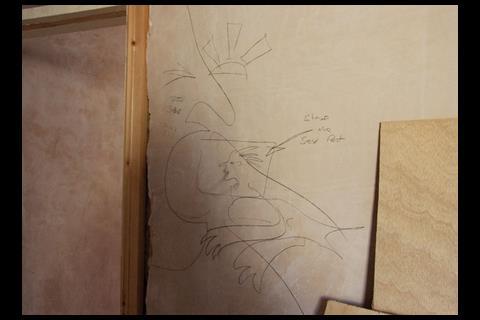

The house is a wreck. The workmen may not have called Arrowsmith “love”, but the kitchen wall features a pencil drawing of “Steve the sex pest”. Plastering has been left undone in random places, and where it has been done often stops well short of doorframes. The plug sockets in the living room have been installed at jaunty angles. There are three places where holes in the structure go through to the outside – usually where walls do not properly meet the floor or ceiling. The wiring in the utility room is exposed. In the kitchen, perhaps the worst affected room, there is a 10cm-diameter hole through the wall to the outside. The main plug socket – intended for the cooker – is set in a gouged-out section of broken plaster, with a sawn-off diagonal gas flow pipe left as testament to the builder’s later remedial work to replace it with a vertical connection in compliance with gas regulations.

The standard of workmanship is summarised in a report from chartered surveyor Chandler Hawkins, which Arrowsmith later hired to inspect the property. Dated 17 September 2007, the report says: “The amount of work undertaken could in my opinion have been completed within two weeks … If the matter is to be resolved by mediation, I would recommend the mediator be invited to inspect the work. It will become immediately apparent that much of the workmanship falls well below the level expected of a competent builder.”

TrustMark steps in

Arrowsmith’s first step was to contact the NICEIC, the electrical contractors’ trade body that had handled Keystone’s accreditation. Arrowsmith first contacted the NICEIC on 10 December 2007 but was told that his complaint fell outside its procedures as Keystone had told it that the work was incomplete and had not been energised – so did not represent a safety breach.

This was untrue: the lights were switched on back in February 2007 when Arrowsmith was showing a visitor around the property. After repeated correspondence, a NICEIC inspector called in April 2008 – four months after Arrowsmith contacted them – and ordered the builder back to make it safe.

Keystone’s response was to sort out some of the kitchen wiring and claim the matter was resolved. When it left for the last time, it took the fittings for the kitchen and bathroom it had installed. Arrowsmith says he paid for these, but Keystone maintained it was owed money for them. It also said it was due £13,411 for extra works.

Gary Smith, a former director of Keystone, says the faults Chandler Hawkins identified reflected the fact that the building was a “job in progress” when Keystone left following a payment dispute. He said: “With any job in progress, even two weeks from the end, you’ll look around and think ‘Cor blimey!’” He added: “We’d only just started up the company and we felt we’d been misled over the amount of work. The lesson we’ve learned is: always get a written contract.”

If the Quality Mark had been in force, Arrowsmith could have now begun proceedings to trigger the warranty that Keystone would have been obliged to carry. TrustMark’s core criteria state that customers should be offered an extended warranty for work done, but Arrowsmith says he never was. In the absence of any enforcement procedure or way of verifying whether he had been offered the cover, his only recourse was to go back to the NICEIC, where he was told that as the remedial work had been completed, the matter was closed.

He continued to petition them, as well as writing to his MP, Mark Hoban, and to the business and enterprise department. Eventually, NICEIC were persuaded to send another inspector. Arrowsmith says he found him trying to fix the wiring around the cooker plug himself: “I told him he couldn’t do that, it wasn’t right. He said he didn’t understand my problem.”

NICEIC maintained that as it only covered the electrical sector, the structural defects in the house were not its problem. Arrowsmith feels misled over this, as the TrustMark logo looks at first glance as though it covers all work. He then began to focus more on complaining to the TrustMark board. A mountain of correspondence between the two ensued, during which TrustMark, which was provided with a copy of the surveyor’s report, acknowledged that there were problems with the house.

In one letter, dated 6 January 2009, Ray Ferris, TrustMark’s head of quality and regulatory affairs, wrote: “The NICEIC agreed that work carried out by Keystone Construction was deficient in several areas.” In particular, the body had certified that it did not meet safety standard BS 7671, which is the basic standard for electrical wiring. TrustMark and the NICEIC held internal meetings over the matter, but these failed to come up with a remedy. One statement that Arrowsmith found particularly galling came in a letter from Ferris dated 6 January this year. In it he says he has been “made aware” that Arrowsmith chose Keystone because he had used them before, rather than because they were registered with TrustMark.

I said it wasn’t good enough, and they started shouting and calling me effing picky and saying they thought I was a mate. I said I wasn’t going to be intimidated in my own home, but to be honest I was frightened – they’re big blokes

At this point, it is easy to see why Arrowsmith has been so angry for so long. Even if the statement were true, what use is a consumer protection scheme that allows the watchdog to use telepathy to evade its responsibilities? And if it were true, why would that mean that the TrustMark guarantee was no longer in force?

In another letter, Arrowsmith is told TrustMark does not become involved if there is a legal dispute between the parties. Although Arrowsmith had received a letter demanding payment from Keystone’s solicitors, he does not believe this should have stopped him seeking redress.

TrustMark was acting within the letter of its law on this point, but the final straw for Arrowsmith came after Keystone entered into voluntary insolvency in October 2008. When Arrowsmith went to the TrustMark website he found that it was still being promoted. The firm’s details have since been removed, but a screen grab from 22 February shows that it was there then. Under TrustMark’s criteria, firms are promoted as being financially sound – however, smallprint on its website advises that data may not be up to date.

Between then and now, Arrowsmith has written hundreds of letters to those involved. Finally last month, the NIECEC offered to appoint a contractor to complete the electrical work at its expense, or replace it if necessary. The “goodwill gesture” was made without any admission of liability. However, Arrowsmith has been told that the cost of repairing the whole property will be £24,874, which he says he cannot afford.

A statement from NICEIC says it investigates every complaint it receives. It continues: “NICEIC did all it could within its operating procedures to resolve Mr Arrowsmith’s dispute – specifically with regard to the electrical work, as is our remit. NICEIC ensured that the electrical installation was safe and set up a mediation procedure. TrustMark were satisfied that NICEIC had done considerably more than is required of a scheme operator. However, we do have some sympathy for Mr Arrowsmith and we have said that once his structural work is ready, NICEIC will ensure his electrical installation is safely completed at our cost.”

Arrowsmith’s experience may well be atypical, but he is furious that Keystone could present itself as TrustMark-registered while his ordeal was taking place. “Other people would have been totally unaware of what they were getting into,” he says. “This experience has been the worst of my life.”

TrustMark’s response

How many complaints does TrustMark receive?

We presently have about 12,000 firms approved and registered and some of these are licensed for one or two trades. This gives us a coverage across the UK of 17,179 registered trades. As an estimate, if we assume each firm does three jobs a week for 48 weeks a year, this means there are 1.72 million jobs done a year by TrustMark firms.

In many cases the consumer complains directly to the tradesmen or to their scheme operator and the complaint is easily and quickly resolved but within TrustMark we receive an average of three unresolved complaints a week, or one for every 10,000 jobs completed by a registered firm.

We accept that no scheme is perfect and there will always be misunderstandings or unresolved complaints between tradesmen and clients and regrettably we will also come up against rogue tradesmen or consumers.

NICEIC said it only covers electrical work, so the structural defects were not its responsibility. Is there a problem that the TrustMark logo can be used by the builders without saying it is only for one area of their work?

All registered firms use a logo that gives details of the scheme operator through which it has joined, and an indication of the trade covered. This can also be confirmed by using our website search facility, so Keystone Construction, does not appear under “general builders” but as an “electrician”.

In a letter from TrustMark to Mr Arrowsmith it says “your choice of contractor was not because of their TrustMark status” but because “you have used them previously”. Why would this make any difference?

I refer you to our five-step complaints process (www.trustmark.org.uk/if-things-go-wrong), which was applied in this case. TrustMark becomes involved in complaints only if the operator fails to follow procedures.

Mr Arrowsmith says he was never offered a warranty for the work done; he should have been under the TrustMark core criteria. Do you have any comment on this?

TrustMark cannot prove this as true or false. It is unfortunately one party’s word against the other. All a TrustMark-registered firm can do is offer an additional warranty under Financial Services Authority regulations.

Mr Arrowsmith may well have been offered one and decided not to pay for it. We have no way of knowing for certain.

When Keystone entered into voluntary insolvency in October, TrustMark continued to promote it on its site. This is despite one of the points in the core criteria relating to financial stability.

TrustMark has no direct contact with registered firms. All communication is via our scheme operators, who are in the best position to make decisions about registered firms. Many firms enter into voluntary insolvency to try to protect all parties and keep the business going rather than just going to the wall. Would it be right to cut routes to trade and so survival because a business is trying to act responsibly?

The reference to financial probity made within the TrustMark core criteria refers to the scheme operator, not the registered firm. That said, the operator will always reference-check all registered firms on entry into TrustMark and monitor their status afterwards.

Did you offer Arrowsmith redress, and if so can you give details of this? Most of the letters say as you cannot find fault with procedures the matter is closed.

TrustMark is not in a position to offer redress and has never done so directly. We can only investigate whether a complaint has been handled correctly by the scheme operator. TrustMark was satisfied that NICEIC had done considerably more than was required of them, and so the matter as far as TrustMark is concerned IS closed. Mr Arrowsmith can pursue the builder through the courts if he is still not satisfied.

TrustMark said once legal action had been started between Arrowsmith and Keystone it would not get involved. Why is this?

The complaints process stops if either party starts legal action. A complaint cannot be handled in two places, and legal jurisdiction will always take precedence over decisions made by our scheme operator.

Have you had any experience, good or bad, with TrustMark?

Original print headline - Betrayal of trust

1 Readers' comment