Exclusive: Blacklisting history of Crossrail’s industrial relations manager emerges in court papers

The scandal of blacklisting threatens to entangle the largest engineering project in Europe after it emerged that Crossrail’s industrial relations manager was an established blacklister in a former role.

Following recent parliamentary questions on alleged blacklisting on the £15bn London rail project, an investigation by Building has found that the manager, Ron Barron, was named by an employment tribunal two years ago as a blacklister at his former employer, the contractor CB&I.

The revelation that he went on to work in such a sensitive role at Crossrail is significant because it raises questions about how thoroughly Barron’s record was checked or acted upon by the Crossrail client team.

It will also be seized on because of ongoing claims by the union Unite that 28 workers were unfairly removed from the project over a dispute with a shop steward who claims to have raised serious health and safety concerns (see below).

Crossrail strongly denies any link between Barron and the contractual move which led to these workers losing their jobs.

Speaking from his desk at Crossrail’s Canary Wharf office on Tuesday (20 November), Barron said: “I can’t comment on anything.”

The tribunal, which took place in November 2010, awarded steel worker Philip Willis £18,000 compensation after finding that CB&I had unlawfully refused him work in 2007 because of his trade union activities.

Willis was on the construction industry blacklist held by the now defunct Consulting Association (CA).

In its judgment, the tribunal said that Barron - then a senior HR manager at CB&I - was responsible and had contributed information to the CA as well as consulting its database almost 1,000 times in a six-month period in 2007 to carry out checks on workers.

Labour’s shadow business secretary Chuka Umunna, the MP who raised parliamentary questions, said Building’s revelation raised further “serious questions” about what was known about Barron. “We need clear assurances that blacklisting is not in operation,” he said.

A spokesperson for Crossrail said Barron was “not a Crossrail employee” but was employed by its project delivery partner Bechtel.

He said: “Crossrail Ltd is responsible for employees directly employed by Crossrail Ltd. Crossrail requires all companies working on the project to comply with the law, including the prohibition on blacklisting.”

He added: “Crossrail is not aware of, and has seen no evidence of, blacklisting of any kind in connection with the Crossrail project.”

A Bechtel spokesperson said Barron “was engaged as a consultant before the decision of the industrial tribunal case … was published, and we were not aware of the case. We requested references and he came highly recommended.”

Barron is understood to be retiring from Crossrail next month.

CB&I was unavailable for comment.

Update: Bechtel has said that Barron is now “no longer engaged” on the Crossrail project.

Previously Barron had been due to leave the project next month.

Bechtel statement in full: “Bechtel does not tolerate any behaviour that is unfair or unethical. The individual concerned was engaged as a consultant before the decision of the industrial tribunal case against his previous employer was published, and we were not aware of the case.

“We requested references and he came highly recommended by independent bodies within the industry. The individual is no longer engaged on the project”.

What happened to the 28 workers?

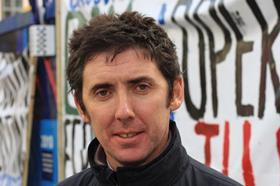

Every morning for the past eight weeks, Frank Morris, pictured, has mounted a street protest at various Crossrail sites across London.

Morris, an electrician with a young family, was working as a union shop steward at Crossrail’s Westbourne Park site for tunnelling specialist EIS, a subcontractor of Crossrail’s western tunnels contractor BFK – a JV comprising Bam Nuttall, Ferrovial and Kier.

He and his union, Unite, claim that he and others were victimised for raising concerns about the potential overloading of the escape chamber on the huge boring machine being used, which would provide a potential refuge for workers in the event of a major emergency such as a fire.

Building understands the dispute is now being negotiated through mediation service Acas.

Morris told Building: “The chamber was designed for 20 people but [the machine] regularly had 27 or 28 people on it.”

He claims that Crossrail reacted badly to this challenge and was so intent on removing him from the project that it terminated the entire EIS contract in September, resulting in himself and 27 other workers losing their jobs.

A spokesperson for Crossrail said this is “simply untrue”.

He said: “A contract between BFK and EIS ended in September as the work they were carrying out to commission the first two tunnel boring machines had been completed with tunnelling now under way. EIS subsequently made 28 workers redundant.”

EIS and BFK declined to comment.

No comments yet