Web exclusive: Will Jones returns to landmark sustainable building the Wessex Water operations centre near Bath and reveals the full post occupation data on the scheme

Overview

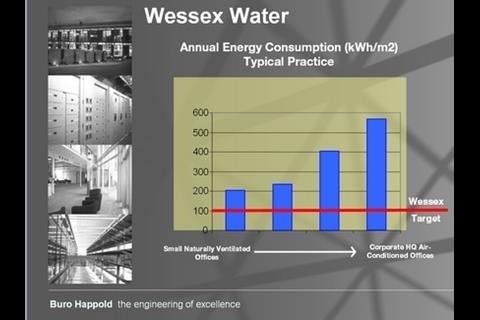

This building was dubbed as the UK’s greenest when it was completed in 2000. The building was an award winner on its completion, winning accolades such as Office of the Year and Project of the Year in 2001. It is largely naturally ventilated; rain water is recycled; hot water is solar heated; heat pump technology has been employed; and, the building was used as a test bed by the BRE for its BREEAM 98. But, the million dollar question is does it still deserve those plaudits? Is it still green? Does it still perform to the original design parameters?Holistic solutions

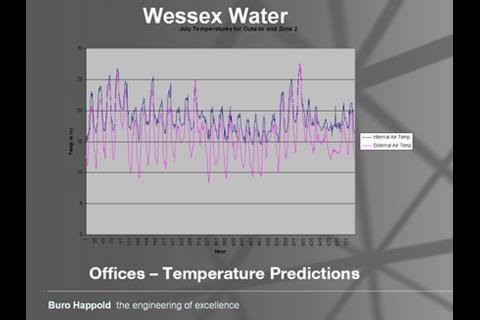

The initial portents on the success of the building are good. On arriving at the forecourt of the centre there’s a bus parked at the kerbside. It’s a free bus for use by staff and local people, ferrying them from the hilltop site into the heart of the city of Bath. This is the first evidence of what is billed as an all encompassing sustainable design.The view from the main reception looks out across meadows and rolling hillsides but wait, the foreground isn’t a meadow at all but a mature green roof over part of the west wing of the building. The atmosphere inside the 10,000 sqm building is pleasant, fresh and good to work in, even on a warm June day. Spaces are open plan, bright and new looking, even though the building was completed in 2000.

The Building

Designed by architect Bennetts Associates and engineer Buro Happold, the Operations Centre sits on a sloping site on the outskirts of Bath. Its east side comprises three two storey office wings, each linking with a wide double height internal ‘street’, which runs from the north to south of the building. To the west of this street are the executive suite, meeting rooms, plant rooms, a staff restaurant and kitchen, as well as outdoor relaxation areas.The two sides of the building are quite distinct from one another. Light steel frame construction with fully glazed facades and an outer layer of solar shading is the format for the easterly office spaces: while a much heavier stone clad approach with wide overhanging eaves is used to the west. “Each is in response to climatic conditions,” says Buro Happold associate Simon Wright. “The heavier west aspect screens the office wings, reducing solar gain, while the glazed east facades promote maximum daylight ingress.”

Monitoring and education

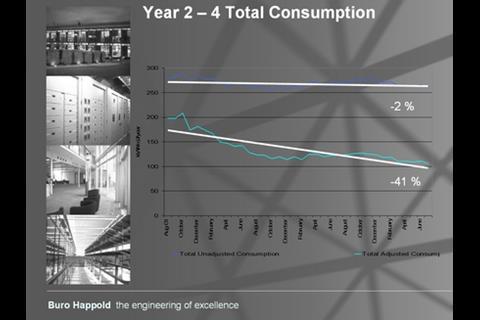

So how is it performing? Buro Happold has answers because ever since the Centre opened it has monitored the centre’s performance in a scheme part funded by the client. “The building needed 12 months to settle down, and for the handover to be properly completed. It takes time to translate the theory of how a building operates into practice,” says Wright. “During that time problem solving was required. In cold weather the building did get cold so we used thermal imaging and visual inspection to identify weaknesses in the building envelope.“As a team we dealt with the weaknesses quickly. Then at one year after completion we started a monthly process of collecting data on gas, electricity and water consumption and comparing it to the benchmarks we had originally set at the design stage.”

Initially, energy consumption at the centre was above target, so Buro Happold had to look at ways of reducing it. “On the heating side, initially we focused on the fabric to eradicate any leakage but we then also looked at reconfiguring the building management system (BMS) to try and improve the way that the heating systems responded to the heating demands,” explains Wright.

“Getting the users to understand and work with their building is of paramount importance"

Electricity and education

“Electrical energy is more difficult to deal with. A lot of the building’s energy use is from the server rooms,” he says. The Centre has a larger than average electrical requirement due to the hardware required to monitor all of Wessex Water’s pipelines and servicing activity – the control room looks like something NASA would approve of. “However, within the office areas, circulation spaces and meeting rooms, small power and lighting loads had to be addressed,” continues Wright. “There were two issues initially: the amount of energy consumption out of working hours in the offices – pcs and lights being left on – and the operation of the daylight and PIR sensors, which were not working as well as the could have done.”The answer was a company-wide education programme on how the building works and how staff should interact with it, as well as the installation of a raft of metering to each individual part of the building. The electrical plant room is now aglow with the red digits of meters recording each sub main, which Buro Happold uses to keep tabs on energy use. “Both aspects are invaluable,” says Wright. “Getting the users to understand and work with their building is of paramount importance. And, with the metering, we can see exactly the amount of electricity each area of the building is using and, if necessary, instruct the facilities manager or staff to act to alter it.”

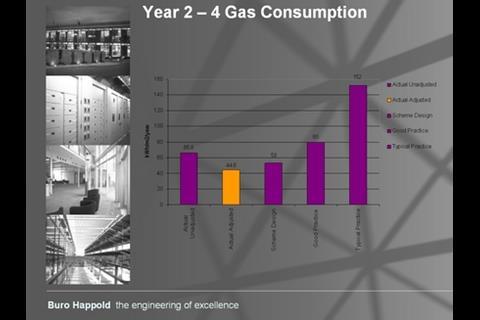

The centre is now operating within all of the design benchmarks laid down by the design team at the outset. Adjusted electricity consumption is slightly above the scheme design target but gas consumption is below and has shown a significant drop since recent BMS reconfigurations. Mains water consumption is well down on targets, too, taking the overall total energy consumption below the scheme design targets.

Lessons learned

What would Wright have done differently in hindsight? “The server rooms are a major power user – some 40-45% of total electrical energy used. You can’t do much about the power used by computer equipment but we could look at how we deal with the essential cooling of that equipment. Maybe we would use a borehole now, where as when we designed the building it wasn’t deemed viable.“Computer use is only going to rise in the future but technologies are more mature now: bore holes and wind turbines are becoming more economically viable. And, peoples’ motivation is now different. Energy consumption and also carbon emissions; both have to be considered. We were focused very much on energy consumption at the time. Now, we design more holistically and take into consideration carbon emissions and alternative energy sources.”

Get the basics right

The technologies used in the Operations Centre play a part in its efficient running. However, more importantly, the design of all aspects of the building make it a successful sustainable project. From its overall orientation on the site to holes cut in exposed steel beams to promote air flow; or, the positioning of heat producing electrical equipment such as printers and photocopiers out of the main office space, each adds to the building’s successful operation.“It is about understanding the physics of buildings and acting accordingly at the start of a project,” says Wright. “You can use all kinds of technology and innovations but make sure the basics are right and you are well on your way to realising your ambitions for the project.”

No comments yet