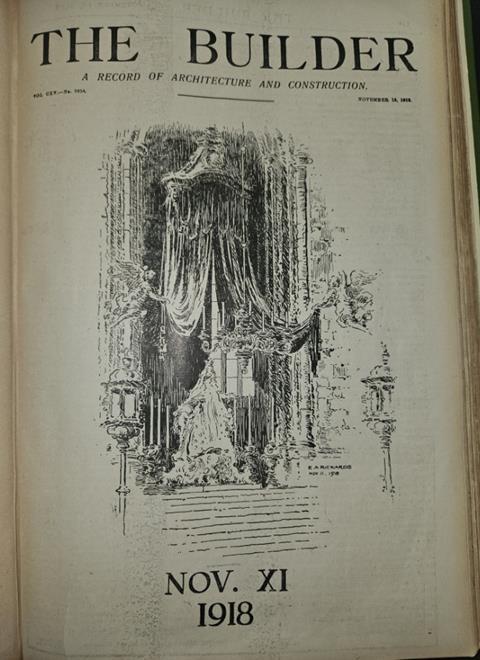

The Builder looks ahead to a new era for the industry as peace returns to Europe

At 11am on 11 November 1918, the war which had dominated the pages of The Builder for four and a half years finally came to an end.

The magazine published a special issue to mark the end of hostilities following the signing of the armistice between the allied powers and Germany. While the sense of relief was palpable, there was much uncertainty about what would come next. Large swathes of Europe lay in ruins, and a shortage of manpower in Great Britain had set the scene for the rise of the Labour movement in the 1920s.

Extract from leading editorial, 28 June 1918

RE-BUILDING IN FRANCE AND BELGIUM

From the shores of the North Sea to the borders of Switzerland lies a belt of land of varying breadth over which the armies of Germany and the Allies have passed, the former committing every conceivable act of wanton spoliation and destruction, while the allied forces have been forced in many cases to destroy buildings for reasons of military necessity. Not only churches and cathedrals, but farmsteads, villages and cottages have been converted into heaps of rubbish, and the destruction, which, in former wars, affected a comparatively small number of isolated towns and villages, has left its mark on several hundred miles of Europe.

The devastated area will remain for all time a colossal monument to the destructive forces of war, and will contain little or nothing which has come down from the past. East and west of it will be found the records of centuries, but the devastated regions will belong to the twentieth century alone.

Extract from leading editorial, 15 November 1918

THE FLOWERS OF VICTORY

So here is Victory; and with Victory, Peace. Victory such as we never knew, for the whole historic world never saw its like; and Peace, an old friend, but never recognised as we recognise her to-day.

There are people who may be said to have never known a day’s health, because they have never experienced a week’s illness. It was almost so with us. The wars of our generation had scarcely ruffled our peace. They had never brought home to hearts in England the chill fear which dare not speak aloud its inmost dread; they had never gnawed at our food nor clutched at our savings, never frozen our hearths or blackened our hopes as this war, in its darker hours, had done. Bitter and desolating as had been their mowing down of young life, their thrust into the happiness of homes, they none of them flung their sickle with such long-drawn cruelty into the growing corn of England’s manhood. But now the lifting of the veil of these four dreadful years has shown us the beauty, the joy, the abiding consolation of that dear companion Peace, who left us, in that August that seems so long ago, so little prized then because so steadfast and, it seemed, so sure.

And what shall we do with our treasure regained? First, with all strength of mind and voice, give thanks to the God of Battles and the Prince of Peace. No empty or formal thanksgiving will this be, but the outpoured gratitude of full hearts. All England, having given thanks where thanks are due, first to the overruling Power that sent to earth for a season not peace but a sword, and secondly, to those men - our brethren - who took the sword that Heaven had thus so strangely sent, may then set, nay, must set, her house in order. And what of our own corner of this world of triumph - the little household of architecture? What have we before us? On what vision of hope and duty have our eyes opened on this daybreak of victorious peace?

We are like, it seems, some poor relation who has inherited suddenly the money, the lands, the home, and the possessions of a distant kinsman of great wealth. Every glance shows us new vistas of the park and pleasaunce which has unexpectedly become our own; every search finds new beauties of garden and house. Every key turned in cupboard or cabinet reveals unsuspected jewelry, unimagined books, unthought of household goods, things of use, things of beauty, things of rarity to which our eyes, in the days of our straitened life, had been strangers. To catalogue these in the very moment of first blissful possession, to say which shall give us our first enjoyment among them, how we shall order them, how we shall set them forth, how we shall profit by them and ask others to hare in them - all this seems an impossible task for the first days of breathless surprise.

But we must draw ourselves to the work. These possessions - to carry on the metaphor - must at least be “valued for probate”; somebody must go through these rarities one by one. The possessor, in this case, is the best steward of his own possessions, and if he does not take reckoning of them himself there are others, just critics of his indifference, who will call him to account and tell the world of his neglected trust. So let us give our account. Longer acquaintance with our acquisitions will, it is true, bring fresh hoards to light; we cannot at first sight be sure how much we possess, but we must begin at once with what we see - truly, a good pile - and so order ourselves and our time as to make the finest use of it all.

We must face bravely and broadly, our new opportunities. The pent-up dam of war’s restrictions in architecture is about to burst

First of all, to look where pleasant duty lies, we recognize what we owe to the men of our own Art who have taken actual part in the war. We must make sure that, as far as in us lies, not one of those men shall suffer any avoidable loss by his period of soldier life. Their welcome back to England must be a hospitable welcome, which bids them share to the full the opportunities of our craft. What is too good for those men? What is too much to ask of us?

Many of these warrior architects left England at the moment when their feet were just planted in full hope on the lower steps of the stairway of art. No crowd of our making, no jostling, no unwillingness of the helping hand, must hinder their attempts to start again at least on the step where they left off. The suggestion that this might be so need only be made to be repudiated, but it will be worth while to remember that the opportunities of helping these younger artists who have done so much for us and at so great a risk to their own careers, are opportunities of gold.

Others - older men - young enough to fight, but not too young to have reached that success which shines on brilliant workers in very early middle age, may have made even greater sacrifices. In their case, our opportunities may be more difficult and all the more golden. Let none of use lose this treasure.

Again, there are the men - the boys, shall we say? - with whom architecture had been little more than an act of dedication, whose very training had scarcely begun. What shall we do for them? They will surely, as part of their welcome home, have their share in that improved education which we hope will be one of the glories of the new era of architecture.

The education of the architect, the amelioration of which is no new idea born of this present moment of excitement, but the dream of many men who have this matter at heart, will go forward, we are sure, with new hope and new force under the energy of England’s reconstruction. It is too big a theme for enlargement here; but it is at least the subject of strenuous study to many of our leading men, and it is not too much to say or to hope that the time is near when the keenest effort will be made, not merely to add value to the young architect’s training, but to aim in that training at the production of designers who shall be, as men and architects, wiser, abler, more learned, more imaginative than their predecessors.

Next, we must face bravely and broadly, our new opportunities. The pent-up dam of war’s restrictions in architecture is about to burst. At first, no doubt, the stream will merely trickle, but the torrent will come. How shall we swim with it? Borne helplessly along or thrusting boldly through the current? We have no doubt of England in this matter. Her architecture of the great post-war period will be known in centuries to come as a marked epoch. But - and here we may differ from some whose aspirations are set upon some great break from the traditions of the past, or at least upon some bold casting aside of the bondage of style - we do not believe that those men who set forth with the primary idea of producing work unlike the work of bygone years will be the most successful in the verdict of posterity. It is enough to say this: England will have new needs, England will have new materials. Probably the best and the most original work will be produced by the men who, trained in historic architecture, yet fix their minds wholly and primarily on faithful fulfilment of the new needs and faithful use of the new materials. Such a man’s sincerity to his practical problem aided rather than hindered by his academic knowledge, will produce, whether he consciously aims at it or not, original work.

More from the archives:

>> Nelson’s Column runs out of money, 1843-44

>> The clearance of London’s worst slum, 1843-46

>> The construction of the Palace of Westminster, 1847

>> Benjamin Disraeli’s proposal to hang architects, 1847

>> The Crystal Palace’s leaking roof, 1851

>> Cleaning up the Great Stink, 1858

>> Setbacks on the world’s first underground railway, 1860

>> The opening of Clifton Suspension Bridge, 1864

>> Replacing Old Smithfield Market, 1864-68

>> Alternative designs for Manchester Town Hall, 1868

>> The construction of the Forth Bridge, 1873-90

>> The demolition of Northumberland House, 1874

>> Dodging falling bricks at the Natural History Museum construction site, 1876

>> An alternative proposal for Tower Bridge, 1878

>> The Tay Bridge disaster, 1879

>> Building in Bombay, 1879 - 1892

>> Cologne Cathedral’s topping out ceremony, 1880

>> Britain’s dim view of the Eiffel Tower, 1886-89

>> First proposals for the Glasgow Subway, 1887

>> The First World War breaks out, 1914

>> The Great War drags on, 1915 - 1916

>> London’s first air raids, 1918

No comments yet