Building speaks to the project teams working under pressure to finish the Millennium Dome, the London Eye and the Jubillee Line extension in time for New Year’s Eve

How do you celebrate a once-in-a-thousand-year event? Build a giant dome was the solution proposed by politicians to mark the millennium, an idea which was seized upon by Tony Blair once he swept to power with New Labour in 1997.

The Richard Rogers-designed building was not universally loved, however. The Dome would be “a triumph of confidence over cynicism, boldness over blandness, excellence over mediocrity”, Blair claimed in late 1999, words which came back to haunt him as the attraction’s dismal visitor numbers became apparent – barely half of what had been projected.

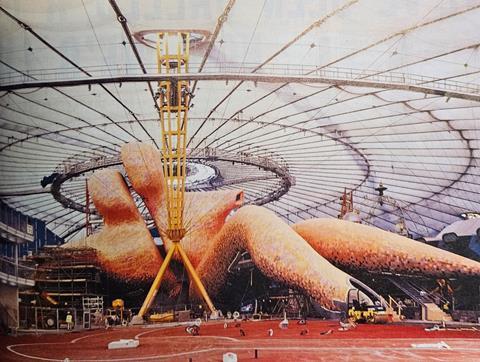

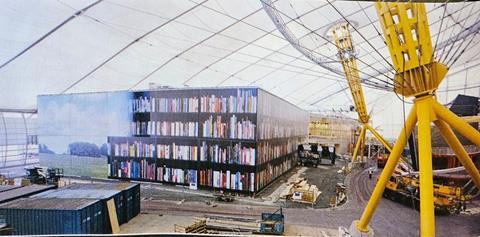

But the scheme’s scale and vision also summed up the era’s optimistic mood, and its construction was an impressive feat achieved in a limited timescale, although pictures published in Building just three weeks before opening, showing internal structures still surrounded by scaffolding, show how close a shave it was to meet its New Year’s Eve deadline.

The dome was the most high-profile of a group of so-called millennium projects including the London Eye and the Jubilee Line Extension, the latter being an unintentional addition only included because it had been delayed by 18 months by the time the big Y2K came around. Here is a series of short interviews published in Building in December 1999 with people working on the three schemes, revealing the pressures faced by the project teams working to get them finished in time.

Feature, 10 December 1999

“The day we failed to get the wheel up we went out and got blind drunk”

The men responsible for getting the London Eye, the Millennium Dome and the JLE open for New Year’s Eve talk about strikes, stress and their local watering holes.

Bernard Ainsworth The Millennium Dome

Regulars at the Pilot Inn, north Greenwich, have grown accustomed to bumping into Millennium Dome project director Bernard Ainsworth. It is here he finds refuge from the travails of running Britain’s most controversial, high-profile construction job.

As project director for joint-venture contractor McAlpine Laing, Ainsworth is responsible for delivering the £800m dome in time for its all-important New Year’s Eve opening extravaganza. Like most top-flight managers, he has his own formula for combating the stresses involved in meeting deadlines. He believes the best way to cope is to sit down and chat about problems over a drink.

“The Pilot is a well-used pub on the peninsula and, in a way, it’s the secret of the dome’s success,” he says.

Ainsworth believes the local has been central to fostering team spirit on the project – and preserving his sanity. He says it is a place where everyone involved in the dome, from client representative David Trench to ground workers, can enjoy a pint and socialise together.

“I often chat there in the evenings to subbies and workers and I find it helps relieve pressure on the project. Nearly everyone is on first-name terms with each other and the landlord.”

Despite being at the centre of the most talked-about construction project in the country, Ainsworth insists he has not felt any more pressure than he usually does when running a large construction project. “In some ways, there’s been less pressure,” he says.

“There’s been a willingness on the part of the contractors to share problems, and I think that’s partly because of the number of social activities we’ve organised at places like The Pilot.”

Ainsworth thinks that media coverage of the project also helped to make his job easier. “Adverse newspaper coverage caused the job to get a protective sheet. It wasn’t nice waking up in the morning and finding your project on the front pages, but whenever the project was attacked from outside, it pushed everyone involved closer together. There have been spats, but adverse press coverage forced us all to lean on one another to prove it wrong.”

As laid back as Ainsworth is, he appreciates that his involvement on such a high-profile project has affected his family life. His home is in Yorkshire with his wife Rosemary and two teenage children, and over the three years, he has commuted there from London often as possible.

“It has been a bit unfair on my wife Rosemary” he concedes. “She’s been very supportive. Building the dome while commuting to Yorkshire at weekends hasn’t been easy.”

How much weight have you lost during the project? I haven’t. I’ve put it on instead. I’m afraid it stems from having a hostelry so close to site.

Low point? The beginning, when we thought the new government wouldn’t give the scheme the go-ahead.

High point? Erection of the first mast; the first sign that we were in business.

Where will you spend the millennium? I hope to be at the dome with my family, but I also intend to visit it later when it’s alive with 30 000 people.

********************

Chris Raven Jubilee Line Extension

In the three years during which he has had to endure wildcat strikes, questions in parliament and even a police raid, Jubilee Line Extension project director Chris Raven admits to having lost some sleep. “It’s true I’ve had one or two sleepless nights,” he says. “But like a lot of people in our industry, I tend to enjoy the stress. You couldn’t survive in construction if you didn’t.”

Raven, project director for M&E contractor Drake & Scull, is in charge of the complex M&E contract for the JLE, which includes dealing with construction’s most volatile workforce. The programme is tantalisingly close to completion, but one station, Westminster, is still under construction and Raven is anxious to complete it by New Year’s Eve.

He finds relief from the stress of presiding over more than 1000 M&E workers by pumping iron before work. A veteran of the Channel Tunnel project, Raven says regular workouts are crucial to help him cope with the pressure of delivering the £3.8bn JLE on time.

“Having a good general fitness level enables me to deal with stress better.”

Raven says the immovable deadline has been the cause of the odd sleepless night. “Everything that happens has to be got around – illness, access problems, whatever. On most projects you can agree with a client to move a deadline in exceptional circumstances, but the millennium can’t be turned back.”

He is clearly one of life’s optimists, however, and his positive attitude has even helped him put the sleepless nights to good use. I’ve taken to having a notebook by the bed so I can jot down ideas and implement them the next day,” he says.

Raven agrees that an understanding and supportive partner is a big help when working on all-consuming projects like the JLE. The Raven family is based in Folkestone and he commutes home at weekends to spend time with his wife and four children. “I miss not seeing my kids during the week,” he says. “On Sundays, I do half a day’s work at home,” he adds, “and, of course, the mobile is on 24 hours a day, seven days a week.”

Like everyone from the industry involved in millennium schemes, Raven has been taken aback by the amount of media attention his project has achieved. “It’s strange seeing your name in print, and some of the things attributed to me have made me question whether I should speak to the press at all. But what saddens me is what the press has ignored.

“On the Channel Tunnel project, several people were killed; that hasn’t happened here. A lot of effort has gone into that and it’s sad no one has seen fit to write about it.”

How much weight have you lost during the project? I’ve lost about half a stone, but that’s been down to working out at the gym.

Low point? The strike in October 1998. Before that, my father-in- law died; that was a real low point.

High point? Opening of phase one of the line in May. In fact, the opening of all the stations has given me a buzz.

Where will you spend the millennium? At home in Folkestone with family and friends.

********************

Tim Renwick London Eye

Tim Renwick, the man charged with getting the giant London Eye millennium wheel turning on new year’s eve, is not a disciple of modern

management mantras. For one thing, he doubts if there is a formula for dealing with the issues he has had to face since the £35m project started on site more than 12 months ago.

Renwick, project director for construction manager Mace, likes a challenge, but even he has come close to meeting his match getting the 135m diameter wheel upright. Problems he has encountered range from system failure to environmental protesters invading the site.

The project even fell prey to the laws of the sea when the wheel’s glass capsules, shipped to the site via the Thames, were held up midstream because of high tides. Renwick took all these hiccups philosophically, and, in true construction tradition, took his project team off site to the nearest pub for a drink:

“The day we failed to get the wheel up, we all went out and got blind drunk. The next day we just got on with it.”

West End pubs aside, Renwick believes old-fashioned competition has been key to the project’s success. “All the normal management stuff goes out the window on a project like this. Peer pressure is what works - no one wants to let the team down.

“We’ve been ruthless to drag this project in on schedule – don’t forget, this is a two-and-a-half-year programme condensed into 14 months.”

Like others involved in millennium projects, he cites the immovable deadline as the most significant factor causing on-site stress. “Obviously, you can’t move the millennium, so you’re eating, sleeping and drinking the project 24 hours a day. People aren’t getting holidays. They’re working long hours and we’re pushing the team almost to breaking point. But we’re on target to deliver it.”

Renwick has found himself thrust into the media spotlight. Client British Airways sent him on a course to learn to handle his newfound fame, but no amount of media training could have prepared him for the day he arrived at work to discover the wheel had been occupied by environmental protesters.

“I said at the time there couldn’t be anything else that could hit us, and Monday morning the protesters were at the top of the wheel. They were probably protesting for a good cause but I wish they’d gone somewhere else.”

Like many people in the industry, Renwick seems to enjoy some degree of stress, but he admits the project has had an impact on his wife Patricia and his children:

“I have had a few restless nights. The moment people find out I’m working on the wheel, it’s all they want to talk about, and that’s been hard on my family. My son is constantly talking about Daddy’s big wheel. It’s been a great project; it’s London’s Eiffel Tower. But I’m knackered; I wouldn’t want to do another like this for a while yet.”

How much weight have you lost during the project? My weight has gone up and down during the project. But at the moment it’s about where it was when the job started.

Low point? On the jokey side, I suppose when The Sunday Times described me as having a none-too-pretty face. On a more serious note, when the first lift failed.

High point? When the last capsule was fitted to the wheel.

Where will you spend the millennium? On site. Celebrating, not building

More from the archives:

>> Nelson’s Column runs out of money, 1843-44

>> The clearance of London’s worst slum, 1843-46

>> The construction of the Palace of Westminster, 1847

>> Benjamin Disraeli’s proposal to hang architects, 1847

>> The Crystal Palace’s leaking roof, 1851

>> Cleaning up the Great Stink, 1858

>> Setbacks on the world’s first underground railway, 1860

>> The opening of Clifton Suspension Bridge, 1864

>> Replacing Old Smithfield Market, 1864-68

>> Alternative designs for Manchester Town Hall, 1868

>> The construction of the Forth Bridge, 1873-90

>> The demolition of Northumberland House, 1874

>> Dodging falling bricks at the Natural History Museum construction site, 1876

>> An alternative proposal for Tower Bridge, 1878

>> The Tay Bridge disaster, 1879

>> Building in Bombay, 1879 - 1892

>> Cologne Cathedral’s topping out ceremony, 1880

>> Britain’s dim view of the Eiffel Tower, 1886-89

>> First proposals for the Glasgow Subway, 1887

>> The construction of Westminster Cathedral, 1895-1902

>> Westminster’s unbuilt gothic skyscraper 1904

>> The great San Francisco earthquake, 1906

>> The construction of New York’s Woolworth Building, 1911-13

>> The First World War breaks out, 1914

>> The Great War drags on, 1915-16

>> London’s first air raids, 1918

>> The Chrysler Building and the Empire State Building, 1930

>> The Daily Express Building, 1932

>> Outbreak of the Second World War, 1939

>> Britain celebrates victory in Europe, 1945

>> How buildings were affected by the atomic bombs dropped on Japan, 1946

>> Rebuilding the House of Commons chamber, 1945

>> Planning the postwar New Towns, 1945-46

>> The Festival of Britain, 1951

>> The world’s first nuclear power station, 1956-57

>> Building covers the 1964 election

>> Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral, 1967

>> The new London Bridge, 1973

>> Queen Elizabeth II opens the Barbican Centre, 1982

>> Trouble at the Lloyd’s building, 1986

>> How Broadgate was built at record speed, 1986

>> Planning Canary Wharf, 1982-88

>> The collapse of Olympia & York, 1992

>> The construction of Waterloo International, 1992

No comments yet