Alsop & Störmer’s Stirling Prize-winning library is given a rave review by Building’s impressed, if slightly confused, architecture critic

Few buildings in London are as baffling as Peckham library. Designed by Will Alsop and Jan Störmer, it actively set out to confound passersby with its playful and almost random assemblage of features. Its eccentric upside-down shape, its wonky columns and the charming red “beret” on its roof were designed, in the interests of promoting literature, to persuade locals to have a look inside, even if just out of curiosity.

When they did venture through its doors, the building was even more surprising. Three large “gourds” filled the library space, poking through the roof, while one wall was almost entirely covered in De Stijl-esque coloured window panels.

The building was an immediate hit with architecture critics, beating both Marks Barfield’s London Eye and Norman Foster’s Canary Wharf station to win the Stirling Prize in 2000.

Feature, 22 October 1999

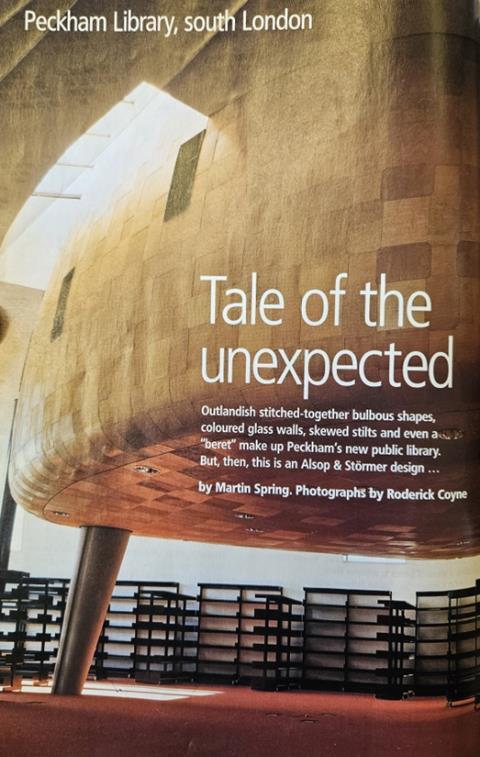

Tale of the unexpected, by Martin Spring

Outlandish stitched-together bublous shapes, coloured glass walls, skewed tilts and even a “beret” make up Peckham’s new public library. Bu, then, this is an Alsop & Störmer design…

For the new Peckham Library in south London, architect Alsop & Störmer has stood the traditional public library on its head. Quite literally so: the main library hall is perched four storeys above an empty void.

Venture inside the library hall and you are confronted by an even more unlibrary-like spectacle. The double-height space is dominated by three great gourd-like objects that are so large they burst through the roof. The gourds bring to mind vats in a brewery, although instead of copper, they are covered in a curious stitched patchwork of plywood.

These are not the only visual surprises awaiting unwary visitors to the library, which is due to open in January. In fact, the entire building, inside and out, is a heady mix of weird shapes, vivid colours, unorthodox materials and outlandish juxtapositions.

On one side, the library hall stands on seven gravity-defying stilts leaning at giddy angles. On the other, it rests on a narrow 7m wide building strip, so that the horizontal and vertical forms fuse together into an inverted L-shaped block five storeys high. And above the roofline peeks a vermilion-coloured flying saucer-shaped lid, nicknamed “the beret” by the architect.

Aside from its upside-down arrangement and rooftop hat, the building is faced in three unorthodox and quite unrelated cladding systems. Variously

opaque, translucent and transparent, they switch with unnerving abruptness at the corners. Three sides are sheathed in a patinated copper skin punctured by tiny windows. In contrast, the ceiling and flank wall to the void below the library hall are faced in an undulating diaphanous mesh of narrow stainless steel rods. And on the fourth side, the external face of the five-storey wing is clad in a sheer, transparent curtain wall, with large panels of yellow, magenta and turquoise glass that create a variegated pattern of colours across the entire wall.

Flouting architectural convention gives a particular thrill to Will Alsop, designer of the newly opened North Greenwich station on London’s Jubilee Line Extension and British architecture’s leading enfant terrible. Alsop rejects the neo-modernist mainstream practised by Wilkinson Eyre, Hodder Associates, Lifschutz Davidson and other former protégées of Lords Foster and Rogers.

“That is a polite, rigid modernism trapped by rationalism,” he says. “Our buildings are the real modern architecture.”

The element of surprise

For his redefined version of modern architecture, Alsop takes an unapologetically sensuous and emotive approach - one that is partly inspired by contemporary painting and sculpture and one where surprise plays a major role.

“We are always thinking about how to produce a pleasurable experience, such as the wash of daylight on vertical walls and the curved gourds in a rectangular building that pop through the roof in a cheeky way. We enjoyed designing this building. There’s a sense of joy about it and I’m absolutely confident this comes through to the users.”

But what, you may ask, have such musings to do with the building’s function as a library? Alsop’s answer is to quote the advice of his client, Southwark council’s chief librarian Adrian Olsen. He said the only way to get people to use a library was to attract children below the age of 10. The sense of joy and surprise in the building is intended to hook the child in us all.

Indeed, the council’s brief stated: “Local people must be able to relate to the architecture and design as well as to the services provided, and they should feel pride in, affection for, and ownership of the building.”

The council’s urban regeneration director, Fred Manson, planned the library to open on to a new landscaped pedestrian square and stand close to a new health and fitness centre, so that together the two buildings would service a healthy mind and a healthy body.

In its own contrary way, the new library building manages to address all these functional, social and practical issues.

Why is it upside-down?

In Alsop & Störmer’s scheme of things, the upside-down L-shape is not as arbitrary as it first seems. “We wanted to create another gateway to the new square,” says Christophe Egret, Alsop’s fellow director. “So, the building is formed as an arch between Peckham Hill Street and the square.

“We raised the library hall 12m above the ground so it doesn’t feel like a weight above your head, and we lined the ceiling and side wall with undulating stainless steel mesh to reflect the light and make the place feel safe. This creates a sheltered space in its own right that can be used for public events and a portico through which you enter the building.

The obvious challenge posed by the arch arrangement is how to siphon passers-by off the street and up four storeys to sample the books and services on offer in the overhead library hall. Alsop & Störmer’s solution was, first, to line both sides of the five-storey block with transparent glazing, so its contents - although not those of the library hall - are highly visible, and second, to make the vertical route up to the library hall as pleasurable as possible. The pleasure is generated by the coloured transparent glazing panels, which cast bold colour washes on walls and floors, and by more stainless steel, draped down the centre of the stairwell.

The three lowest floors of the narrow block contain a collection of neighbourhood, information and learning services. On the ground floor, a council one-stop shop directs local enquiries to the relevant departments. Above it are an adult learning centre, with 50 study places wired into the national libraries’ computerised learning system, and a children’s library.

Saving the best for last

On reaching the key fourth floor, visitors are treated to a double and quite unexpected spectacle. On the north side, a wide vista opens up over the rooftops to central London’s forest of towers. On the other, there is the library hall itself, filled with its three mysterious gourds.

“We elevated the library above the ground so that it would be a little bit apart from the normal humdrum life of Peckham,” explains Egret. “People would come out of the lift and into another world. We wanted to reveal views of the city that people wouldn’t have seen before, And we wanted the library to be like an attic, where people can concentrate without distractions.”

The library hall is a plain rectangular white box with tiny windows that frame the sky, and perimeter skylights through which even daylight spreads over on the walls below. The three gourds are raised on concrete legs above reading tables. Their rounded surfaces are faced in small squares of thin plywood stapled together like leather patchwork, a sensual, organic surface set off beautifully by the flat white walls of the enclosing hall.

The three gourds all contain meeting or activity rooms. The two outer gourds, which are fully enclosed, have an irresistible womb-like feel inside, making them inspiring settings for children’s group activities or intimate community meetings. The central gourd, in contrast, is cut away so that it is open to and visible from the library hall. It serves as an African-Caribbean study centre.

Patchwork and Brillo pads

The finishes of the patchworked gourds were inspired by the sculpture of Richard Deacon; their embellishments also have a sculptured appearance. The internal light fittings, devised and assembled by artist Joanna Turner and nicknamed “Brillo pads”, are soft cushions of aluminium chain mail that diffuse the light from point sources. The skylights to the two enclosed gourds are shaded “butterflies” - hinged pairs of curved plywood shutters. And the open central gourd is encircled by clerestory windows above the roof level and shaded by the large vermilion beret that is so eye-catchingly visible from neighbouring streets.

Alsop & Störmer’s new library building sports enough architectural surprises and delights to ensnare the most anti-literate inner-city dwellers. Whether they will continue to take the lift up to the fourth floor over the coming years will, however, depend on the services offered by the council’s library department.

How did they do that?

Will Alsop, seniuor partner of architect Alsop & Stormer, is keen to reassure British clients that his non-conformist designs do not entail greater risk than more conventional building forms. “None of our buildings has fallen down, they’re all built on budget, and they’ve all got good maintenance records,” he says.

Although the Peckham library’s technology is not its aesthetic centrepiece, as it is with the buildings of Richard Rogers Partnership and Nicholas Grimshaw & Partners, the design is backed by considerable technical expertise. It is also a sustainable, low-energy building, gaining an “excellent” rating under the Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method.

The three large pods in the main library hall were constructed on frameworks of timber carcassing. “At first we thought of using concrete because of its thermal mass,” explains project architect Andy Macfee. “But it would have been quite heavy and expensive. Metal construction was also expensive. We then thought we would try the craft of boat-building, but boat-builders imagined that the structure would have to survive force-eight winds.”

In the event, the contract for the gourds was awarded to Cowley Structural Timberwork of Lincoln, which has a track-record in church domes and worked on Branson Coates’ Oyster House, the star of last year’s Ideal Home Exhibition. The irregular double-curving form of each gourd was prefabricated as three horizontal slices measured off 3D computer models. The timber carcassing was craned into position and then stiffened with laminated veneer timber boarding to form a structural skin.

The “patchwork” cladding to the gourds takes the form of small squares of 1.5mm thick aeroplane plywood that were overlapped and carefully stapled to the underlying boarding, with the copper staples exposed like patchwork stitching. The interior surfaces were sprayed with a white, sound absorbent finish.

Building structure

Designed by structural engineer Adams Kara Taylor, three main elements make up the overall structure of the inverted L-shaped building.

The five-storey vertical block is supported on an in situ concrete frame that includes diagonal bracing and deep floor troughs. The frame is exposed, and its surface has been sand-blasted and finished in a light-grey Keim paint to give a soft, smooth appearance like foam rubber. The overhead library hall is supported on deep steel trusses at 3m centres. The seven spindly stilts that prop up the outer side of the library hall are 323 mm diameter steel columns filled with concrete.

Paradoxically, their raking arrangement provides additional structural stability to the library hall above.

Energy-efficient environment

Despite its deep-plan library hall and fully glazed vertical block the building is designed to rely on natural ventilating and daylighting for most of the year. Services engineer Battle McCarty reckons that annual energy consumption in the building will be as low as 182 kWh/m’, and cost only £17,065 a year.

Skylights and north-facing glazing are designed to distribute daylight evenly throughout the building.

The building is cross-ventilated through opening windows and vents, with additional mechanical extract ventilation required in summer. No artificial cooling is needed, as the exposed concrete frame absorbs excess heat. Added to that, little solar gain is expected in summer, as the five-storey window wall faces north and the south-facing glass facade is shaded by the projecting library hall. Not least, the library hall is ventilated and cooled by a natural stack effect that draws cool fresh air from the shaded void directly below and out through rooftop vents. The clerestory windows to the African-Caribbean pod are shaded by the rooftop beret with its peak projecting southwards towards the sun.

The vertical block’s extensive windows are of low-emissivity double glazing panels to provide good thermal insulation.

More from the archives:

>> Nelson’s Column runs out of money, 1843-44

>> The clearance of London’s worst slum, 1843-46

>> The construction of the Palace of Westminster, 1847

>> Benjamin Disraeli’s proposal to hang architects, 1847

>> The Crystal Palace’s leaking roof, 1851

>> Cleaning up the Great Stink, 1858

>> Setbacks on the world’s first underground railway, 1860

>> The opening of Clifton Suspension Bridge, 1864

>> Replacing Old Smithfield Market, 1864-68

>> Alternative designs for Manchester Town Hall, 1868

>> The construction of the Forth Bridge, 1873-90

>> The demolition of Northumberland House, 1874

>> Dodging falling bricks at the Natural History Museum construction site, 1876

>> An alternative proposal for Tower Bridge, 1878

>> The Tay Bridge disaster, 1879

>> Building in Bombay, 1879 - 1892

>> Cologne Cathedral’s topping out ceremony, 1880

>> Britain’s dim view of the Eiffel Tower, 1886-89

>> First proposals for the Glasgow Subway, 1887

>> The construction of Westminster Cathedral, 1895-1902

>> Westminster’s unbuilt gothic skyscraper 1904

>> The great San Francisco earthquake, 1906

>> The construction of New York’s Woolworth Building, 1911-13

>> The First World War breaks out, 1914

>> The Great War drags on, 1915-16

>> London’s first air raids, 1918

>> The Chrysler Building and the Empire State Building, 1930

>> The Daily Express Building, 1932

>> Outbreak of the Second World War, 1939

>> Britain celebrates victory in Europe, 1945

>> How buildings were affected by the atomic bombs dropped on Japan, 1946

>> Rebuilding the House of Commons chamber, 1945

>> Planning the postwar New Towns, 1945-46

>> The Festival of Britain, 1951

>> The world’s first nuclear power station, 1956-57

>> Building covers the 1964 election

>> Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral, 1967

>> The new London Bridge, 1973

>> Queen Elizabeth II opens the Barbican Centre, 1982

>> Trouble at the Lloyd’s building, 1986

>> How Broadgate was built at record speed, 1986

>> Planning Canary Wharf, 1982-88

>> The collapse of Olympia & York, 1992

>> The construction of Waterloo International, 1992

>> Aftermath of the Bishopsgate bombing, 1993

No comments yet