It won the Stirling prize, but many doubted whether it would ever win over the locals. Nine years on, Martin Spring went back to Will Alsop’s Peckham library to find out

Peckham library in south London can be read as a textbook case of signature architecture mobilised in the cause of urban and social regeneration. In the nineties, Southwark was the second most deprived council area in England, and Peckham was one of its worst areas. Housing was poor, unemployment high and the GCSE pass rate was a third of the national average.

So, the £6.75m library was commissioned by the Labour-run council as part of a £265m regeneration package for Peckham. The 2,500m2 building, designed by Will Alsop, was completed in 2000 and was greeted as an architectural wonder – albeit a bizarre one. It went on to win that year’s Stirling prize and a Civic Trust award two years later.

Now, nine years after completion, is the building fulfilling the goal set for it? Does it attract people from deprived backgrounds to the world of books, learning and education? Has it launched a generation of IT-orientated libraries? And has it acted as a catalyst for the regeneration of this rundown borough?

Well, we’ll come back to those questions. The first thing to say about it is that the building’s strangest and most in-your-face feature is also a fundamental handicap. By perching the library hall high up on the fourth floor, Alsop overturned the golden rule of retailing: display your wares as prominently as you can to pull in passers-by. In an area not noted for its love of scholarship, this could be a serious defect.

That said, this handicap has not prevented Peckham from becoming the most popular of Southwark’s 13 branch libraries. Over the past year, it has attracted 35,000 visits a month, more than its counterpart in the leafy suburb of Dulwich and 9% above the target set by the council.

Membership of the library is higher than the borough average for all age groups up to 44, and this popularity reaches its peak for teenagers, who record a 14% membership within the population of 15-to-19 year olds – twice the average in Southwark. This partly fulfils the vision of Daniel Olsen, the former borough librarian and building client, who argued that the only way to hook people as library users was to attract the under-10s.

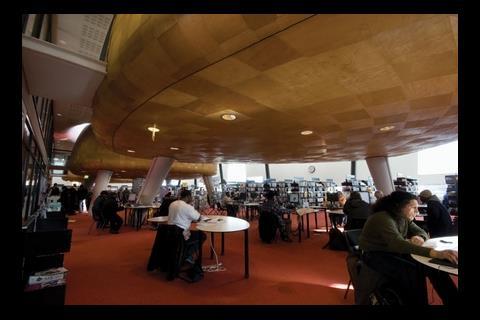

The main library hall on the fourth floor is an expansive, double-height space punctuated by three of Alsop’s trademark pods: large gourd-shaped enclosures floating in the upper void. This weird arrangement combines 60 secluded study spaces below the three pods with light and airy areas for shelving and circulation.

From 9am, when the library opens on weekdays, the desks fill up rapidly with students and others looking for quiet study space with or without an internet-connected terminal. According to librarian Linda Foster, the 25 PC terminals record a 94% usage. Beyond that, she notes that a wireless broadband network was installed in 2006, and this has attracted a group of internet users who bring their own laptops.

“It’s calm, quiet and a big space,” says student John Salmon. He adds that the library is well stocked and staff are “very helpful”. Fellow student Cathy Asante also likes the spaciousness. But she also points to a deficiency: “Sometimes I’m here all day and I’d like something to eat, but there’s no cafe.”

As for the pods, these are not living up to their promise, even though their external patchwork coats of paper-thin plywood shingles remain fascinating and unblemished. The central one is an open mezzanine floor that floats like a dinghy over the library shelving below. It had been fitted out as an Afro-Caribbean library, but Foster says: “Books looked incongruous there, and people didn’t go up to visit it.” Accordingly, she brought the collection downstairs and refurnished the pod with four-square study desks, which also look incongruous.

Peckham has become the most popular library in Southwark. Over the past year, it has attracted 35,000 visits a month

One of the two enclosed pods had been designated as a toddlers’ den reached from the children’s library by a narrow spiral staircase. But Foster keeps most toddlers’ activities in the lower library, which is, in any case, a more attractive space. The other pod is a slightly forlorn, bare, windowless meeting room lined in wood-chip wallpaper.

By far the most entertaining pods are a couple of study carrels just large enough to accommodate a brace of hobbits. They are housed in the compact local history library on the second floor, but history librarian Bob Askew finds them annoying as they get in the way of shelving and circulation.

As to the mystery of why the library hall should have been hoisted five storeys above pavement level, the answer is only revealed when you step out of the lift. Continuous windows stretch along its north and south sides, and these display breathtaking panoramas of London.

It is the children’s library on the north side that exploits the views to most exhilarating effect. From here, the London Eye, St Paul’s Cathedral, the Gherkin and the whole skyline of central London are on display. The clear-glazed double-height window wall also frames a vast amount of sky, and a random pattern of large panes tinted pale yellow, pink or blue add to the spectacle. Little wonder that Foster has all but abandoned the enclosed children’s pod.

Down at the building’s main entrance, the scene is glaringly different. The small door is cut out of a continuous, prison-like facade of wire mesh. The entrance lobby is cramped and municipal and offers visitors no enticement to view the splendours a short lift ride away. Even the award plaques from the RIBA and the Civic Trust have been hidden away.

These awards have spread the fame of Peckham library across the world. In recent months, Foster has received groups of visitors from Croatia, Nebraska and South Korea, and has even presented a paper at a conference in Singapore.

So is the library better known and more admired overseas than in its home neighbourhood? This is stretching things too far. In Building’s straw poll of visitors, most were attracted by architectural as well as practical matters. “It’s a building that draws young people like myself,” says Salmon, who adds: “It makes me less bored when I’m here.” Fodaay Kamara says: “It looks very wonderful from the outside, and it’s the same inside.” The strongest praise come from assistant librarian Lesley Palmer, who says: “I absolutely love it here. It’s like a spaceship and it’s always busy. I’ve been here four years and I don’t want to move to another library.”

After nine years of operation, what has been the impact of the library on the social well-being of Peckham? “The library is a beacon that pulls people towards it,” says its literary development officer, Sandra Agard, who reels off a series of the bookish events that helps this process. “Children and adults are proud to use this world-famous building, so it shapes the community.”

Southwark council is now ruled by a Lib Dem–Tory coalition, but it has not dismissed the library as the weird indulgence of a previous regime. Just the opposite: it intends to develop another library building as the centrepiece of regeneration of nearby Surrey Quays. An “iconic” building stands near the top of its published wishlist for this proposed library, Piers Gough has been appointed architect, and his design is shaped like an inverted concrete pyramid. So the free-thinking, rule-breaking spirit of Peckham Library lives on in inner-city Southwark.

Will Alsop vs the vandals of Peckham

How does Will Alsop’s outlandish chunk of look-at-me designer architecture stand up to the wear and tear and vandalism of the tough, gritty, inner-city district it stands in? The answer is not too badly on the whole, although with one glaring exception. A more intractable problem is that, being a special architect-designed building using non-standard products, it is difficult, costly and time-consuming to repair. The exceptional vandal damage and the repair problems are both exemplified in the window wall covering the entire north face of the building. In a savage act of vandalism, six of the storey-height double-glazed panels at ground-floor level were smashed, three of them by air-gun pellets. Putting a brave face on the incident, librarian Linda Foster says: “I’ve worked in buildings in leafy suburbs, where you find broken windows every Monday morning. Here it’s only happened once, but it’s going to be a big job to put right.” She then explains that glazed panels were no longer produced by the original supplier and instead had to be procured from France, while the tinted film had to be supplied by the original architect. Meanwhile the repair costs had risen to £48,000, and the unsightly smashed panels have remained untouched and open to view for several months. Alsop decided to protect the main entrance side of the building much more securely with a strong chain-mail of metal mesh (pictured). The side walls are clad above first storey height in green patinated copper panels, a few of which are blotchy after graffiti was removed by sandblaster. Another irritating maintenance problem concerns the recessed ceiling lights in the library hall. As the hall is a double-height space and access is restricted to a pair of passenger lifts and a narrow staircase, scaffolding must be laboriously erected to replace the light bulbs, and since the library is open seven days a week, this means overnight. But in its first year of operation, the library was closed for a week just for this single routine activity. These days, bulbs are replaced out of opening hours, but on the day of Building’s visit several bulbs had failed and were waiting for this occasion. Last year, Southwark council outsourced all maintenance and repair work to several private firms. Since then, even day-to-day maintenance and repairs are lackadaisical. Assistant librarian Lesley Palmer says the heating system is often out of action, and library user Birger Lindberg from Sweden is annoyed by lift breakdowns. “Every second week they don’t work,” he says. On the plus side, it is a relatively low-energy building with no air-conditioning, though librarian Foster concedes: “It is true that the library does get quite stuffy in the summer months.” Accordingly, standalone air-conditioning units were retrofitted in the two enclosed pods and the main staff office.

Changing rooms

The building’s innate adaptability is demonstrated by the One Stop Shop (above), which lies next to the lift lobby on the ground floor and dispenses all council services including Homesearch for people on its housing waiting list. The One Stop Shop is intensively used, dealing with 300 inquiries a day, according to manager Carla Walker. Accordingly, it was expanded in 2006 by 70% in floor area by adding a mezzanine floor, compact fit-out and air-conditioning designed by Alexei Marmot Associates. The building’s double-height space was able to accommodate the extra mezzanine floor, its robust reinforced-concrete frame designed by Adams Kara Taylor took the additional load without needing new foundations, and dead space below its escape-stair landing housed the new air-handling unit. Only the air-conditioning chillers could not be fitted into the original building and have instead been installed in a 2m high black box a few paces away.

Downloads

Plan

Other, Size 0 kb

Postscript

Original print headline: ‘Peckham turns over a new leaf’

2 Readers' comments