David Higgins has to deliver the 2012 Olympics with a fraction of the money that China had to spend. Oh, and he has to regenerate a swath of east London at the same time. To kick off our countdown to the Games, Sarah Richardson asked him how he’s planning to do it

At the foot of Mount Kilimanjaro, a warning sign is nailed to the Marangu Gate. “If you have a sore throat, a cold or breathing problems do not attempt to go more than 3,000m above ground level. All climbers must be physically fit.”

Glacier-covered, despite being on the edge of the equator, Africa’s highest mountain tests the endurance of the most experienced climbers. About 20 to 30 people die on its slopes every year and almost 1,000 more are evacuated suffering from dehydration, altitude sickness or just sheer exhaustion.

David Higgins, the chief executive of the Olympic Delivery Authority (ODA), chose to scale this mountain after a training regime that consisted solely of taking his cappuccinos skinny and walking up the escalators on the tube.

He tried to conquer the 4,600m Kibo peak, the highest on the mountain, with his son. “We were horribly ill-prepared,” he says. “We just took bags of fruit and dried nuts, which are completely useless when you’re running out of energy. We should have brought chocolate and glucose but …” He collects himself. “Anyway, that was interesting. That interested me a lot.”

The story is hardly a glowing testament to the organisational credentials of a man in charge of delivering all the work required for the 2012 Olympics, along with the little matter of regeneration of London’s East End. Especially given that during his first 33 months in the job, the budget went from £2.4bn to £9.3bn and the housing market plunged into freefall. So is Higgins still the right man for the job?

One thing after another …

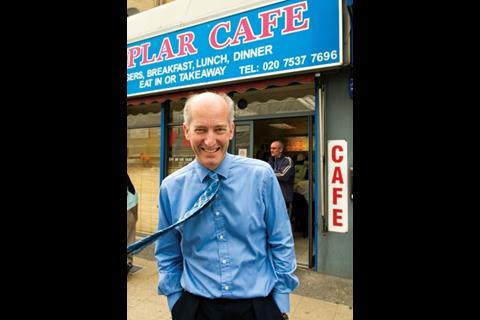

“This project has constant challenges … you could call them crises,” says Higgins, staring into his coffee (unskinny, this time) in Poplar high street on a gloomy August morning. The cafe is round the corner from the ODA’s Canary Wharf offices and in the heart of the area the Olympics is supposed to regenerate. “Two years ago, it was the land deals, and whether or not we could negotiate with people like the Reuben Brothers [who owned a 50% stake in Stratford City before they sold it to Westfield for £110m]. You had Ken Livingstone talking about it, and there was a lot of speculation in the press.

“Then there was the contaminated land.” Higgins says this one was a bit hairier: “We were a year behind schedule and we stopped building the tunnel for power cables for 12 weeks while we did decontamination work. The concern then was that if this was rolled forward, the project would be late.”

As the quiet Australian raises his voice slightly above the sound of sizzling bacon in the background, it is hard not to notice the irony of talking to Higgins in a setting with so many frying pans and, well, fires.

He recounts the nine months spent altering the stadium and aquatics centre designs to bring their budgets down to a manageable cost; at £303m, the aquatics centre is still more than three times its original price. “That was a hell of a lot of work. Now of course it’s the village, and in nine months it’ll be something else …”

A team with ‘tensions’ Higgins is quick to recognise his weaknesses. “I know areas I like to focus on and areas I don’t. I’m no lawyer or accountant, so I rely on experts, particularly regarding the public sector. The complexities of planning, the statutory process, these are difficult things.”

To run an operation on the scale of the ODA, he believes you need a team not only with complementary expertise, but with “tensions, where people get into disputes”. That may be so, but surely you can have too much of a good thing? Take Jack Lemley, the former ODA chair who left with a £388,000 payoff 11 months into his job amid reports of clashes with staff.

Higgins is cautious when talking about Lemley, but admits he has not spoken to him since he left. “I haven’t, no. But it’s a long time ago now – it feels like a long time ago.”

He is far happier to talk about John Armitt, the present incumbent. “It’s great to be able to tell stakeholders: here’s someone who’s done it before and knows what’s going on.”

Trouble in the village

The Olympic village looks like being his biggest challenge – you could call it crisis – to date. This year’s meltdown in the housing market has forced Higgins to scale back the number of apartments in the area from the 4,200 envisaged to about 3,000, the minimum needed to give every athlete a bed.

Developer Lend Lease has been unable to secure funding from its banks, which means the government may have to take on the risk of building the apartments. An interim arrangement, whereby Lend Lease acts as a contractor with no equity stake has now been signed, although Higgins is still adamant he will have a final solution in place by December.

The former chief executive of regeneration agency English Partnerships (EP), Higgins is convinced that the market will recover in time for the sale of apartments in four years time. Launching into an animated discussion of housing economics, he cheerfully predicts: “The number of houses that will be built in the next three or four years is going to be substantially down on all estimates. Household formation in the UK isn’t going to change substantially but supply will, so in five years time there will be a shortage. Supply and demand is going to correct with a vengeance.”

He says he is unaware of reports that Carillion, the media centre contractor, is not being held to the 30-day rule, but says that if this were the case it would not be tolerated

He sounds convincing, and his views are given weight by his experience of delivering Sydney’s Olympic village as head of Lend Lease. But with no funding agreement in sight he needs to be – the £1bn village is facing a shortfall of about £400m. He says it’s “highly unlikely” that his former employer Lend Lease will remain without an equity stake in the project – you hope his confidence is well placed, because without this, the regeneration of the East End will be an altogether tougher proposition.

Higgins says the opportunity to lead this regeneration was the main thing that attracted him to the ODA. He is more at home in Poplar’s rundown greasy spoon than you might think: when he joined EP, one of the first things he did was buy a travelcard and tour London’s most deprived areas, including many of those around Stratford.

“I remember spending some time in a cafe in Canning Town. There’s a market square there and a little cafe where I’d sit and watch people and try to understand their situation and the economic drivers.”

Even then, he was struck by London’s capacity for redevelopment. “I remember going to Catford and walking around the shopping centre and the old dog track, and thinking it’s 20 minutes to two major city centre rail stations on two different lines and yet there’s absolutely nothing here. If this was in Paris or Sydney, it would have been developed much earlier.”

The shadow of Wembley

The problems in the financial markets have not just hit the village. Pricewaterhouse Coopers recently revealed that the number of construction companies falling into insolvency had risen 35% since this time last year, adding extra pressure to Higgins’ management of the Olympic supply chain.

The runaway cost of British sport’s last national construction project, Wembley stadium, were caused in part by the high number of insolvencies in the supply chain, with the client effectively having to bail out or replace many of them. Higgins is, of course, alert to the comparison. He says the ODA is running its own credit checks on suppliers to attempt to ensure it is not left exposed. “We haven’t introduced any new criteria, but we’re monitoring closely our exposure to individual contractors,” he says.

He also counters reports that the ODA is taking a lax attitude to its commitment to only employ firms that pay within 30 days. “In the current market particularly, we don’t want our supply chain to delay cash payments – this doesn’t help the industry.”

He says he is unaware of reports that Carillion, the media centre contractor that employs 65-day payment terms on some contracts, is not being held to the 30-day rule, but says that if this were the case it would not be tolerated.

One inadvertent effect of the credit crunch is that it has increased the number of bidders wanting to win work, thereby strengthening Higgins’ hand. “Eighteen months or two years ago it was much harder to get people to tender,” he says.

Another development Higgins did not foresee when he took charge was that much of the industry would be accused of breaking competition law by the Office of Fair Trading (OFT). He is keeping an open mind on the outcome of that probe, but is determined that the ODA will not be caught up in the scandal. “Since the OFT inquiry, we’ve sent notes to all our procurement people and contractors. We make it clear such practices aren’t tolerated.”

With some of the Olympic build programme’s biggest names, including Balfour Beatty, under investigation, Higgins will not be drawn on what action, if any, the ODA will take against those found guilty. “Let’s not prejudge investigations, right? They are innocent until proven otherwise.”

Beating Beijing

Leaving the cafe to walk back to the ODA headquarters – the walking is Higgins’ idea, he seems prepared to brave the traffic to point out the infrastructure potential of the area – conversation turns to Beijing.

He is planning to return to watch the opening ceremony on a big screen with his staff, before flying out later to catch some of the Games themselves. Despite confessing that he has never really been one for “sitting and watching sport”, he’s particularly keen to see the handball venue. “What the hell is handball? I’ve got to build one of those?”

Handball aside, he says he’s not fazed by the prospect of following Beijing. “They had a huge number of permanent venues, and we don’t need to do that. London doesn’t have to beat Beijing, and nor should it try. You’ve got to be pragmatic and get 80% there. If you worry about perfection you’ll never get there. So many people just follow the yellow brick road and get lost in the process.”

With 75,000 contracts, dozens of buildings and 30 bridges to go, even 80% is a tough order. But then again, Higgins managed that climb to Uhuru Peak at Kibo in five hours – three fewer than the average. A few skinny cappuccinos and a programme of escalator exercises, and perhaps the next four years won’t be so tough after all.

Higgins’ olympics in one minute

Favourite moment of the Beijing Games?

Britain’s first gold – Nicole Cooke in the cycling

Best thing about the Beijing Games?

Being there

Most surprising thing?

The change in the city since I was last there 16 years ago

Hero of the Games?

Usain Bolt

Favourite Beijing venue?

The aquatics centre

All-time favourite Olympic moment?

Cathy Freeman becoming the first aboriginal to receive an Olympic gold medal in athletics, in Sydney in 2000

Postscript

Original print headline: ‘London doesn’t have to beat Beijing, nor should it try. You have to be pragmatic and get 80% there’

No comments yet