Ben Flatman examines how Gehry’s work evolved from local, materially driven invention into one of the most recognisable architectural vocabularies of his generation

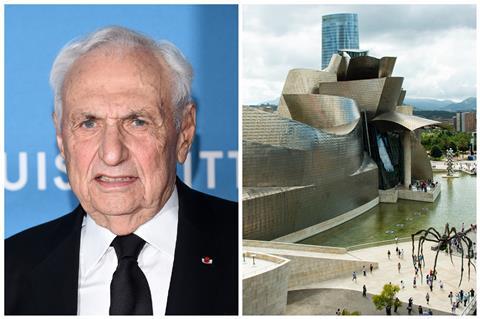

Frank Gehry, who has died aged 96, was one of the few architects whose buildings became part of global popular culture. From his own house in Santa Monica to the glinting upturned hulls of the Guggenheim Bilbao, his work reshaped expectations of what a building could look like and what it could do for a city. He turned architecture into spectacle and, for better and worse, into a brand.

Over time his language hardened into a repertoire that clients could order almost off the shelf. The architect who once wrapped a cheap timber house in chain link and corrugated metal would end up providing the global art market and luxury brands with ever more elaborate vessels for culture and consumption. Yet for all the fame and the titanium billows, Gehry’s most lasting legacy may lie in earlier, smaller projects where the work still feels close to the specifics of place.

Los Angeles beginnings

Frank Owen Goldberg was born in Toronto in 1929 to a Polish-Jewish mother, who had emigrated from Łódź, and an American father, Irving Goldberg, whose parents were Russian-Jewish immigrants. His childhood was shaped by his grandmother, Leah Caplan, who encouraged him to build small cities from the offcuts and scraps brought home from his grandfather’s hardware store. Hours spent assembling these improvised models on the living room floor formed his earliest experience of making spaces and imagining buildings.

In the 1950s he formally changed his surname from Goldberg to Gehry, a decision not uncommon among Jewish Americans at a time when antisemitism remained a barrier in professional life. He later said he regretted it, and in later years sought more actively to embrace his Jewish identity.

In Los Angeles he studied architecture at the University of Southern California, where the stripped modernism of figures such as Raphael Soriano left its mark, even if he later pulled hard away from modernist orthodoxies. A short spell studying planning at Harvard followed, after which he returned to California and went to work for Victor Gruen, the Austrian born pioneer of the American shopping mall (and another Jewish immigrant to the US who Anglicised his own surname). Here Gehry saw at first hand how architecture served the new suburban economy, packaging shopping and leisure as a managed interior world.

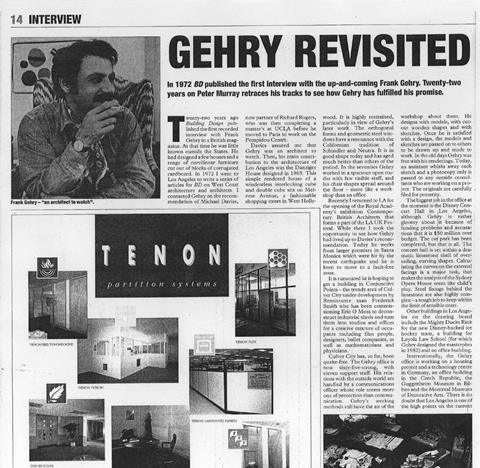

He opened his own office in Los Angeles in 1962. Early work such as the Danziger Studio on Melrose Avenue, completed in the mid 1960s, consisted of simple rendered cubed forms. The project that first drew serious attention in Britain, when Peter Murray interviewed him for BD in 1972, showed none of the later swoops and curls.

In these years Gehry moved in a circle of Los Angeles artists, among them Ron Davis, Ed Ruscha and Claes Oldenburg. Their work with collage, found materials and deliberate roughness fed directly into his architecture.

Santa Monica house and the artists’ city

The turning point was his own house in Santa Monica, bought in 1977 and reworked over the next year. Gehry took a modest timber bungalow and wrapped it in new layers of structure and skin: plywood, corrugated metal, exposed joists, tilted glass and lengths of chain link fencing more usually seen around car parks. Parts of the original house were left visible inside this new carapace, so that old and new jarred together. Neighbours were appalled, but for younger architects and critics the house became a manifesto for a more open, improvisatory way of building.

The house crystallised ideas he had been testing in small projects across southern California. It drew on the makeshift character of Los Angeles itself: a city of fragments, signage, service yards and provisional structures. It also owed a debt to the west coast funk art scene, treating cheap materials as a legitimate starting point for serious work rather than as something to be hidden.

Gehry always rejected the neat theoretical labels that others tried to pin on him, but by the late 1980s his work was inevitably folded into the narrative of deconstructivism. The 1988 Deconstructivist Architecture exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, curated by Philip Johnson and Mark Wigley, grouped him with Peter Eisenman, Zaha Hadid, Rem Koolhaas and Daniel Libeskind as part of a loose tendency towards fragmentation and controlled disorder. Gehry insisted he was simply following the logic of his models, while Johnson and Wigley saw the show less as defining a style than as a deliberate provocation, intended to unsettle a discipline they believed had drifted into predictability and caution.

Vitra, Prague and the European turn

Gehry’s first European project was the Vitra Design Museum at Weil am Rhein, completed in 1989. The campus had begun with Nicholas Grimshaw’s crisp factory shed; Gehry’s addition was something else entirely. White rendered forms twist and collide under zinc roofs, a small museum that reads as frozen movement. It was his first European building and signalled a shift from the raw bricolage of Los Angeles towards a more sculptural, self-conscious language.

A series of projects followed in the early 1990s that showed him testing how far this approach could stretch. In Venice, Los Angeles, the Chiat Day offices, completed in 1991, incorporated a huge binoculars sculpture by Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen on the street front, the everyday office floors slipping in behind. The building, now part of Google’s campus, was a wry fusion of art and commerce.

In Prague he produced one of his most persuasive European works. The so called Dancing House, designed in collaboration with Vlado Milunić for the Dutch insurer Nationale Nederlanden and completed in 1996, sets a swaying glazed tower against a more solid rendered block. It acknowledges the party walls and cornice line of the riverside, picking up something of the city’s baroque idiom while developing its own, more contemporary rhythm. In a newly post communist city, the building’s humour and lightness felt politically as well as architecturally pointed.

Bilbao, Disney and the age of digital form

The Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, opened in 1997, changed not only Gehry’s career but also the political economy of architecture. The museum’s billowing titanium surfaces and looping internal promenades were developed from handmade cardboard and paper models, which were then digitised using advanced aerospace software. Gehry was among the first architects to understand how such tools could turn complex curves into buildable form, and through Gehry Technologies he helped bring that capability into mainstream practice.

Bilbao did more than show off a new geometry. It became the emblem of a wider shift in which cities sought salvation in cultural flagships and global tourism. The so called Bilbao effect, in which a single spectacular building was expected to relaunch a moribund city, turned architects into key players in the global competition for attention, investment and visitors. Gehry found himself at the centre of this new economy, whether he liked it or not.

More than any other building of its era, the Guggenheim Bilbao became a kind of visual shorthand for the city itself. Long before social media turned architecture into global currency, its titanium folds circulated through newspapers, guidebooks and travel supplements as a ready-made symbol of reinvention. The building’s image travelled faster and further than the art it contained, fixing Bilbao in the public imagination and demonstrating how a single work of architecture could stand in for an entire place.

The Walt Disney Concert Hall in downtown Los Angeles, conceived in the late 1980s and completed in 2003 after a long and difficult gestation, is often read as a twin to Bilbao, though in fact it was designed first. The two buildings share a common language of flowing metal surfaces and tightly choreographed interiors, but at Disney this vocabulary is tied back to the city that shaped him, with curling stainless steel volumes wrapped around a warm, timber lined auditorium. Here the approach finds one of its most convincing expressions, rooted in a place he understood intimately.

Maggie’s and the quieter projects

If Bilbao and Disney defined Gehry for the wider public, the small Maggie’s Centre he designed at Ninewells Hospital in Dundee, opened in 2003, shows another side of his work. Influenced by the traditional Scottish ‘but and ben’ cottage, it resembles a small white house under a folded metal roof, opening to generous views over the Tay. It is domestic and precise, a rare moment when his sculptural impulses sit comfortably within a small building shaped by landscape and use. A decade later he followed it with another Maggie’s in Hong Kong, a pavilion inspired by traditional Chinese architecture and arranged around gardens and terraces.

These quieter works are reminders that Gehry could still pare back when the brief demanded, a side of his output sometimes overshadowed by the otherwise growing sense of spectacle.

The 2008 Serpentine Pavilion translated Gehry’s familiar interest in layered surfaces and improvised structure into a temporary timber and glass shelter in Kensington Gardens. Its translucent canopy and timber-clad supports framed a central gathering space, providing a brief London outing for the processes that shaped his larger work.

Brand Gehry and the problem of repetition

As digital tools improved and global capital sought icons, Gehry’s language spread across the world. Residential towers in New York, brick folds in Sydney, a museum of pop culture in Seattle and a neurological centre in Las Vegas each took the familiar ingredients and recombined them. The results were energetic and at times exhilarating, but there was also a growing sense of déjà vu.

The Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris, opened in 2014 for Bernard Arnault’s LVMH group, is in many ways the emblem of this late phase. A solid concrete core, the so called iceberg, is wrapped in vast glass sails that rise above the Bois de Boulogne, a literal vessel for luxury. Technically it is highly complex, with double curved panels and a forest of engineered timber and steel. Yet the visual effect feels like a reworking of known moves, this time in the direct service of a global brand whose own logo incorporates Gehry’s squiggle.

The LUMA tower in Arles, completed in 2021 for the LUMA arts foundation, compounds this unease. A jagged stainless steel shaft rising above the low roofs of the city, it is justified by reference to Van Gogh’s paintings and local geology. It reads more as an assertion of authorship than a response to brief and site. It is hard to escape the sense that at this late stage, the Gehry studio had become detached from place and programme and begun to produce work that was a commodity in its own right.

In this Gehry was far from alone. His generation helped define the architecture of globalisation, as cultural institutions and tech companies alike sought distinctive silhouettes to mark their presence in the world’s cities. Gehry’s early insistence on the specificities of Los Angeles sat uneasily with a later career in which similar formal vocabularies appeared in widely different contexts, often at the service of luxury, finance and cultural tourism.

Rage, rigour and legacy

Gehry was acutely aware of the charge that his buildings were about spectacle. At a press conference in Spain in 2014, asked what he would say to those who dismissed his work as showy, he snapped. He told reporters that 98% of what was built in the world was, in his view, “pure shit”, accused the question of being stupid, and raised his middle finger before explaining that only a small number of people were trying to do something worthwhile. He later apologised and blamed jetlag, having just flown in from the opening of his Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris, but the episode revealed how sharply he felt such criticism.

Behind the response was a real sense of grievance. He saw himself as working painstakingly with models, collaborators and clients who cared, and he bristled at any suggestion that he was simply chasing attention.

However, the longer his career went on, the harder it became to separate the architect from the brand. He appeared in the Simpsons and lent his now familiar curves to ever more far flung commissions. Yet the story is not simply one of self-parody. Across six decades of work he showed that architecture could be both tough and playful, and technically exacting.

For younger architects, the most inspiring part of Gehry’s legacy may not be the crystallised brand of Fondation Louis Vuitton or LUMA, but the restless figure in a modest Los Angeles office, cutting and taping scraps of card, asking what more might be made from ordinary materials and an awkward corner site.

>> Also read: LVMH Foundation for Creation by Frank Gehry

>> Also read: Gehry’s Serpentine Pavilion raises deeper questions

>> Also read: Frank Gehry and Norman Foster celebrate opening of Luma Arles

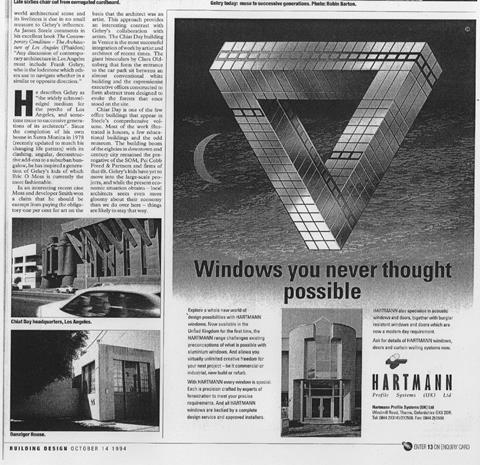

Pictured below, BD’s Peter Murray’s 1994 article recalling his 1972 interview with Frank Gehry

Postscript

Ben Flatman is a contributing editor at BD

No comments yet