Two options for the renewal of the crumbling Palace of Westminster have been presented to MPs. Both would be highly disruptive, costly and take a very long time – most likely several decades. Tom Lowe studies the latest report to find out what is being proposed for the UK’s most famous building

Looking at the latest proposals for the restoration of the Houses of Parliament, there is one detail that jumps off the page. Much has been said about the urgent need to modernise the building, but it is the extraordinary duration of the programme of works proposed – up to 61 years for the longest recommended option – that has caught the attention of the industry.

How can the refurbishment of one building – albeit a very large, grade I-listed building – take more than six decades to complete? The timescale is only 15 years off the time which has elapsed since the last renovation, completed in 1950, implying that, by the time the works are finished, the first parts of the job to complete would be almost ready for restoration again.

Even so, the 61-year option, called “enhanced maintenance and improvement plus” (EMI+) and costing up to £39.2bn, is not actually the longest on the table. Out of the four options under consideration, the longest is a simplified EMI programme which could take 84 years to finish, with a minimum duration of 52 years. It would also be the most expensive, potentially costing £56.3bn if adjusted for inflation, almost three times as much as the entire Crossrail programme.

In a report outlining the four options published this month, the client board overseeing the development of the restoration recommended to MPs that the EMI option should be discounted due to its excessive length and the risks it might pose to those working inside the building during the works. Nevertheless, the fact that an eight-decade-plus programme of works has been given serious consideration highlights the extreme level of complexity involved in restoring a crumbling heritage asset which continues to be the beating heart of the British state and a daily workplace for several thousand people.

The durations of the two EMI options are extended because they have been designed to allow the building’s operations and occupants to remain in place for the majority of the works. In the case of EMI, restoration of the Houses of Commons and Lords would only take place during parliamentary recess periods or outside of operating hours, significantly constricting the time available to carry out work.

Meanwhile, another of the four options, called “Continued Presence”, has also been discounted by the client board, despite its maximum duration coming in at a relatively speedy 45 years and a tempting price tag of just £22bn. This option was struck off in the client board’s February report partly because it would require the House of Lords to relocate to the nearby QEII Centre for up to 33 years.

The cost of further delay

- £1.5m is spent per week maintaining and repairing the Palace of Westminster.

- On average each month sees around 2,900 reactive maintenance jobs raised at the Palace of Westminster, together with around 380 minor works.

- Between 2021/22 and 2023/24 reactive maintenance tasks increased by 70%.

- In the month in which the client board’s report was drafted, issues in the palace included: failure of heating to a significant area of the House of Lords; significant problems with the sewerage system; ongoing loss of toilets in the areas that have reinforced autoclaved aerated concrete (RAAC) as well as four sets of toilets out of action; water leaks into the colonnade.

- Since 2016, there have been 36 fire incidents, 12 asbestos incidents, 19 stonemasonry incidents.

- It is estimated that the cost of delaying starting the delivery phase of the programme is around £70m per year at current prices in nugatory options development and additional reactive maintenance costs

- It is estimated that there would be a further £250m to £350m in the inflationary impact on construction costs across the whole of the programme for each year of delay.

According to the report, MPs had raised concerns that moving the house for this length of time risked breaking its link with Parliament and leading to “unintended changes in culture and procedure”.

In normal circumstances, it would be expected that the occupants of a building undergoing significant restoration would vacate while works are underway. This has been the case with Manchester City Council, which in 2020 moved to a neighbouring building at the start of Bovis’ restoration of the grade I-listed Manchester Town Hall, set to complete next year. With the Palace of Westminster, it is a little more complicated.

Embedded in the floorplan of the building are the day-to-day processes which go into running the country, making laws and scrutinising policy. This includes the size of the House of Commons and House of Lords chambers, the arrangement of division lobbies, the number of committee rooms and the level of access provided to the press.

Much of what Parliament does is interpreted through convention, tradition and the UK’s flexible unwritten constitution. Disrupting this delicate balance for a prolonged period of time has naturally made MPs and Lords, who will decide on what restoration option to take in 2030, jittery that it could open a Pandora’s box.

Their attachment to the long-established formula of Parliament, encapsulated over their fears of a three-decade-long relocation of the House of Lords proposed in the Continued Presence option, has hardly been helped by the recent sustained period of political turbulence which has produced five prime ministers in the past 10 years and the emergence of a new and unpredictable political force in Reform UK.

Which brings us to the fourth option for the restoration, one of only two – along with EMI+ – that has been recommended for further consideration by the client board. The £15.6bn “Full Decant” option is the cheapest and by far the quickest of the lot, taking between 19 and 24 years to complete.

It would see both Houses of Parliament move out of the building for the majority of the works, with the Commons moving to Richmond House on Whitehall for around nine years and the Lords moving to the QEII Centre for 12 to 15 years. The client board has found it poses the least risk to the heritage of the listed building and would require a workforce around 15% smaller over the course of the programme compared to other options.

It might seem like an open and shut case, not least for the Treasury, which is going to have to find the funds for the work. But a full decant has long been the most controversial proposal available to MPs, with more details provided in the client board’s February report unlikely to change that.

The number of seats provided in the temporary House of Commons chamber at Richmond House would be 40 fewer than are in the existing 437-seat chamber, which is already far too small for Parliament’s 650 MPs. The two division lobbies, where MPs vote on proposed legislation, would be situated next to each other rather than on opposite sides of the chamber as currently, potentially changing the dynamics of last-minute changes of heart during knife-edge votes.

The number of committee rooms for scrutinising government would be reduced by 10, to just 12, consisting of eight for select committees and four for general committees. Perhaps most significantly, the capacity of the Commons chamber galleries for the press would be reduced by half, with more than 200 fewer seats.

Meanwhile, the ceremonial functions of Parliament will have to be reimagined. The spectacle of Black Rod knocking on the door of the House of Commons at the State Opening of Parliament would look markedly different for a decade, there would be no Robing Room – used by the monarch to don the crown before entering the House of Lords – and Westminster Hall could not be used for the lying-in-state of any monarch who dies during the period.

MPs and peers have repeatedly raised concerns about the full decant option in surveys, warning the client board that it “risks breaking an important link with parliamentary history” which could lead to “the loss of tradition or a reduced quality of parliamentary scrutiny and debates”. The temporary loss of support offices for the Commons while it is located on the Northern Estate was also flagged as a potential risk affecting parliamentary business.

But, even if full decant is the option which is eventually chosen, there remains the question of how the refurbishment of a near-empty building could take almost a quarter of a century to complete and cost the same as 14 Northern line extensions.

The programme has been in development since 2012, with the current scope of the work decided following a series of meetings held by the client board in 2023. The board considered a range of outcomes for the project from level zero, which would focus on priority areas only, to level five, which would deliver “transformative change”.

Level 0 was the first to be discounted after programme board members concluded it would be “unlikely to meet various statutory obligations”. Levels one and two were thrown out because board members argued they did “not sufficiently meet compliance standards”, while level three “did not allow for future proofing the works [and] provided less value for money”.

This left only the top two levels, with level four eventually chosen because it would deliver “significant improvements to the palace for all those who work in and visit it, while representing the best value for money for taxpayers”. Even so, the board admitted that part of the appeal of level four was “the potential to add additional improvements to the scope for [restoration and renewal] after costed proposals have been approved, should circumstances or the Houses’ priorities change”.

Palace of Westminster restoration and renewal programme timeline

- 2012: Planning for a major programme of works to restore and renew the Palace of Westminster starts

- 2018: The two houses agree full decant as the preferred way forward to deliver the programme

- 2022: The programme is reset, including a requirement to seek a new mandate from both houses and to look at a wider range of options to deliver the programme to ensure value for money

- 2023: Outcome level four is selected as the preferred scope of the works

- 2024: A strategic case is agreed for the programme which recommended the development of three options for programme delivery

- 2026: Preparatory work on a £3bn package of phase one works to start

- 2027: Strategic partner appointed to lead seven-year phase one programme

- 2030: MPs and Lords make decision on which delivery option to progress for phase two

- 2033: End of phase 1 works

Full decant

- 2032-39: Phased decant of the House of Commons to the Northern Estate

- 2032: House of Lords decants to the QEII Centre

- 2040-43: Phased return of the House of Commons

- 2044-49: Phased return of the House of Lords

EMI+

- 2034: House of Commons begins zone by zone decant to Northern Estate, each zone lasting several years

- 2034: Works start on the interior of the Victoria Tower

- 2036: House of Lords decants to QEII Centre for eight to 13 years

- 2040: House of Commons chamber decants to House of Lords for two years

- 2063-86: Works complete

Under the chosen outcome, the programme is targeting a 40% reduction in the building’s operational energy usage and at least 60% of its total floor area to be step-free, up from the current 12%. While both ambitions are laudable, questions remain over the value for money of spending billions saving operational carbon which will be partly negated by the embodied carbon emitted during the works.

Meanwhile, incremental upgrades have already provided step-free access in most of the building’s key public areas. In a comment piece in The Sunday Times last week, Create Streets founder Nicholas Boys Smith argued that “spending hundreds of millions to ensure full access to nearly every back corridor is a luxury this increasingly poor country can no longer afford”.

Shoehorning lifts and ramps into every part of the labyrinthine complex is also not only contestable on heritage grounds, but, along with added measures to improve fire safety, would reduce the net usable space for office accommodation. Similar accessbility improvements would also be needed in the refurbishments to the QEII Centre and the Northern Estate prior to any decant to those locations.

But in a further complication, the client body has admitted to a “misalignment” between the restoration and renewal programme at the Palace of Westminster and the work to prepare the Northern Estate buildings on Whitehall, where the Commons would be relocated. Some parts of the estate are not expected to be ready for occupation until 2039, adding a significant delay to the programme before the restoration of parts of the House of Commons can even begin.

The client board has said it is exploring “mitigations” to minimise the delay, including phased occupation of the Northern Estate buildings, which could allow some restoration works in the palace to start in 2034.

The restoration work itself as proposed in both recommended options is highly complex, spanning four main areas – fire safety and protection, wholesale replacement of building services, removing asbestos and protecting historic building fabric. It will see new fresh air ventilation added to around 80% of habitable rooms, unsafe stonework and windows rebuilt, surface and rainwater systems renewed in line with 2070 climate models, reliable heating and lighting installed and enhanced security measures put in place.

Under EMI+, the building would be split into 14 zones, which would be worked on in stages, with no more than 30% of the building to be vacated at any one time. The House of Commons would move into the Lords for up to two years and the House of Lords would move to the QEII Centre for eight to 13 years, while committee rooms would be refurbished in batches.

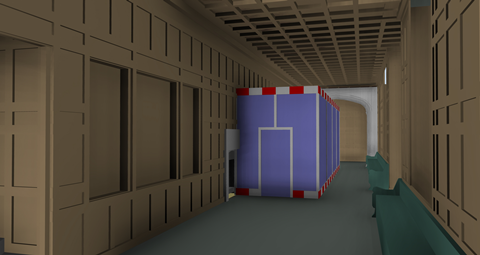

Continued occupation makes the work more complex and adds to the cost, with areas being worked to be surrounded with an acoustic buffer up to 10m thick to reduce noise and disruption to those still working in the building and large parts of the interior to be blocked off with hoarding.

Significant new additions to the palace are envisaged, including a proposed visitor space underneath Central Lobby, new public lifts and stairs leading from this space to the lobby above, a new visitor entrance and underground routes, a new education centre and a major new enclosure within State Officers’ Court for MPs to meet constituents. A new ramp and landings would also be added to the 929-year-old Westminster Hall as part of the wider programme of accessibility upgrades.

All of these interventions will take place within a site with the highest level of heritage protection, in arguably the UK’s most internationally famous landmark and in a building central to the functioning of the country.

All of these factors have contributed to the length and cost of the programme. A pattern of disastrous fires within buildings undergoing restoration – from the Notre Dame in 2019 to the Glasgow School of Art in 2018 and Windsor Castle in 1992 – means fire protection has been a major contributor to both delivery times and cost. While the project will be expensive, assessments have found it will only be slightly higher per square metre than the redevelopment of the Canadian parliament, the most similar parliament building to the Palace of Westminster in terms of building age, architectural design and operation.

The client board has also sought to minimise the programme duration by launching a £3bn first phase of enabling works set to start this year, comprising early underground works, preparations for the restoration of the site’s medieval Cloister Court and the construction of a river jetty for construction deliveries. A procurement process is expected to launch this year for the appointment of a strategic delivery partner or partners, which would then be in pole position to stay on board for the second phase of works when they start in the 2030s.

Regardless of the option chosen, the restoration will cause varying levels of disruption to the palace and the day-to-day operations of politics in the UK. With the less invasive EMI+, large parts of the building’s exterior will be covered in hoarding for decades to come. With the full decant option, the building will be almost entirely covered in hoardings for up to 24 years and the familiar green and red benches of the two houses will seem, by the time the restoration is complete and MPs and peers can move back from their temporary homes, like something from a previous era.

The question now facing the client board is how the public will react to the proposals when they are confronted with the costs and construction time of the delivery options chosen. When MPs and peers vote on the plan in 2030, it is likely to lead to a wider public debate about the best use of taxpayers’ money and the decision taken in 2023 to discount outcomes with a more limited scope is bound to come under greater scrutiny.

The client board described the publication of its latest report as ”marking significant progress towards securing the future of the home of the United Kingdom’s Parliament”. It may not prove to deliver as much progress as the board hopes.

2 Readers' comments