Plenty of young people across the UK are signing up for construction training - the real problem, according to a report out today, is that many are taking courses that simply don’t meet the industry’s needs.

There’s no doubt that construction skills are back on the agenda. After six years in which the industry lost 350,000 staff, 12 months of modest construction output growth means - surprise, surprise - that nobody can find enough qualified tradespeople to do the work. So it was no shock that business secretary Vince Cable made the industry “horror story” over skills the centrepiece of his speech to the Government Construction Summit last week, with the CITB also using the event to launch a high-powered commission to look into the apprenticeships system. This week, meanwhile, the Federation of Master Builders’ State of Trade survey highlighted major difficulties for small contractors recruiting plasterers, bricklayers and site supervisors.

The Greater Manchester economy is a prime example of how this gathering storm impacts projects in the real world. The pipeline of planned construction work in the city until 2017 includes £9.5bn of schemes, driven by the housing market and resurgent private commercial developers. Gary Wintersgill, northern managing director of Kier Construction and deputy chair of the Greater Manchester Chamber of Commerce’s (GMCC’s) contractor council, says: “The market is picking up, and we’re on a precipice. With the boom in London the talent is draining down south.”

In response to this growing threat, GMCC decided to commission a study, the latest version of which will be launched today (11 July), looking in detail at the skills needed to address this pipeline. And the report’s findings - seen exclusively in advance by Building - might not be what you would expect. Contrary to fears that not enough young people are embarking on a career in construction, the report finds ample evidence of interest. The problem is rather that most training being undertaken isn’t actually what is needed.

I speak to people who think they’ve got a vocational qualification but they haven’t. The employer engagement with colleges has not happened properly

Jocelyne Underwood, GMCC

Skills gap

The GMCC report, compiled by construction data firm Barbour ABI, compares Greater Manchester’s £9.5bn pipeline against the CITB’s Labour Forecasting Tool to predict that a total of 65,564 workers will be needed at peak in 2016, with an average of 55,742 staff over the period. This is over 70% higher than the average requirement of 31,796 staff in the previous four-year period (2010-2013), indicating the scale of new blood that must be brought into the sector. Christian Spence, head of business intelligence at GMCC, says: “Being able to recruit skilled staff is the single biggest issue that employers come to us with. It’s about having the right skills at the right time and it’s an overwhelming problem, and it’s a barrier to growth.”

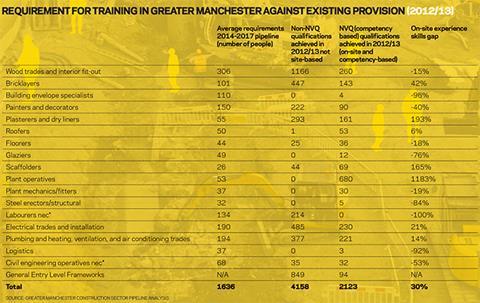

The most important findings of the analysis, however, are in the detail: which trades in particular are required by the city’s construction pipeline (2,243 bricklayers and 577 scaffolders in 2016, for example); what that equates to in terms of training requirements; and how that compares to the existing training provision.

In total, it finds an average of 2,788 people will need to be trained in construction skills per year over the period from 2014 to 2017, an increase of 75% on the previous four years. And rather than the traditional bricklaying and plastering trades, the analysis finds that the most acute shortages are in fields such as building envelopes, steel erection, glazing and civil engineering.But the most striking finding is that only just over a quarter of qualifications currently being undertaken actually include the on-site training element that is crucial to being able to get a job in the industry. These on-site “competency-based” courses deliver the NVQ qualification that is the principal part of construction apprenticeships. In some trades - such as electricians - it is a legal requirement for working; in many others it is simply a de facto minimum requirement for being let onto a site.

Despite this, the vast majority of qualifications taken are instead classroom-based construction “diplomas” which provide an introduction to skills but don’t actually qualify someone to work. So, for example, 312 people took qualifications in painting and decorating in Greater Manchester in 2012/13, against a requirement predicted by the pipeline of just 150. But only 90 of those 312 took a competency-based course, meaning there is a shortfall of 60 people.

And this story is repeated again and again (see the table showing the requirement for training, below) - with only a few exceptions such as plasterering, bricklaying and plant operation showing more people achieving NVQ-level qualifications than will be required.

The impact is already being felt. Anthony Dillon, northern MD for Willmott Dixon, says that specialists are already turning work down on the basis of not having enough staff to fulfil orders. “They’re saying their order books are full and they won’t even look at it.”

Ultimately the concern is that tightening supply will see prices shoot up. GMCC’s Spence says: “Businesses always find a way to get things done, albeit work might be slowed down. But this will drive up costs. For some skills you can already pretty much name your price.”

Bums on seats

The question is, why are trainees taking courses that don’t qualify them? The most obvious place to look for an answer is the colleges and schools. They are given money by the Skills Funding Agency to run these classroom-based diplomas, and some careers advisers seem simply unaware the courses are not vocational qualifications. According to CITB research, 44% of teachers admit they give ill-informed careers advice and 60% do not base advice on available work.

Jocelyne Underwood, construction sector lead at GMCC, says: “A lot of the time I speak to people who think they’ve got a vocational qualification but they haven’t. The employer engagement with colleges has not happened properly.”

This is not to say these courses are useless - they often give pupils who would otherwise leave school and potentially be unemployed, a taster of a construction career. But if the colleges aren’t aware of their low status, it doesn’t necessarily pay them to wise up. Underwood says: “There’s an element of colleges getting bums on seats because it enables them to draw down funding.”

However, contractors can’t just grumble about provision by colleges as the principal cause of this mis-match. The reality is that the number of apprenticeship places - which do give people on-site skills - have fallen by a third nationally in recent years because employers themselves have cut programmes during the recession. Because apprenticeships take up to three years (for a level 3 version) many employers have not had the security of workload necessary to take them on. At the same time the fragmented nature of the industry means apprenticeships are best delivered by specialist subcontractors, firms who have the least clarity of workload and have suffered significant cash-flow problems.

Businesses always find a way to get things done, albeit work might be slowed. But this will drive up costs. For some skills you can already pretty much name your price.

Christian Spence, GMCC

Into this mix the CITB, which recycles the training levy collected from contractors, is supposed to support construction firms who want to take apprentices on. However, GMCC’s Underwood says the funding system, which requires employers to create training plans for apprentices, has been so complex as to put all but the largest contractors off. Adrian Belton, the CITB’s chief executive, last week promised to simplify this system, but it will take a while to change the rules. “It was great to hear him say that,” says Underwood, “because something’s going wrong at the moment.”

Do the maths

What’s the solution? A big step, says GMCC’s Spence, is doing the pipeline analysis to find out where the real gaps in skills are, in order to get the message across to the schools, colleges and funding bodies. This is the second year that GMCC has undertaken this research, and Spence says last year’s study, by identifying the demand, has already resulted in a new provision for steel fixing and formwork joinery apprentices, through civil engineering firm Heyrod Construction. Thirty apprentices joined the scheme in March, and eight other Manchester firms are now supporting the programme, the only apprenticeship scheme for steel fixers outside of London. The Cabinet Office is looking at rolling out this pipeline analysis as best practice to other parts of the country.

Nevertheless problems remain. One example is the shared apprenticeship scheme run by GMCC with contractors in the area, where it underwrites apprentices’ employment in order that firms are not left in the lurch by having to pay an apprentice if work dries up. Of the 120 people to have completed the course, 80% are in permanent employment. However, despite this success it doesn’t qualify for CITB funding, because GMCC gets local colleges to manage the on-site assessment rather than the CITB itself. That means contractors have to pay extra for the service on top of the levy they pay the CITB.

Reviewing the CITB’s funding model for shared apprenticeships scheme is therefore one of three key recommendations GMCC makes in the report. In addition it calls for central funding to be made available more widely on the basis of this type of analysis, and for funding to be allocated to support a specified training provision on public sector contracts.

But the biggest lesson from the analysis is that all parties - including government and the Skills Funding Agency, but particularly colleges and the industry - need to talk more to ensure that the training provision matches the economy’s requirement. As Kier’s Wintersgill says: “The key thing is to get the two sides talking to each other. I’m hoping that colleges will see the opportunity here and set up courses to respond. But it will take time to change their curriculum.”

2 Readers' comments