For too long, designers have been able to get top BREEAM ratings by adding recycling space and bike racks. Now the green assessment tool is toughening up its act with mandatory levels for energy and water use – and a new rank above ‘excellent’.

For 18 years, the environmental assessment method BREEAM has been considered a soft touch. It has faced criticism for its weak and bizarrely weighted ratings criteria and has looked insipid beside newer systems such as the American LEED. But from 1 May that is set to change. The tool’s operator, BRE, has undertaken the most dramatic overhaul in the system’s history. And for architects, that means working harder than ever to provide genuinely sustainable designs, especially those working on government buildings, which will require an “excellent” rating.

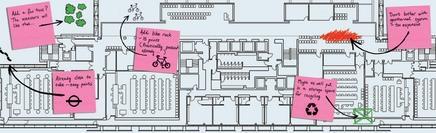

Under the current scheme, architects and engineers have been able to attain “excellence” while paying lip service to low-energy design. For example, they gain credits simply by installing lighting that meets current best practice guidance. Furthermore, factors unrelated to design, such as being close to a public transport hub, or quick fixes such as introducing bike racks or recycling systems, also secure high credits.

More stringent

The revamped tool is set to address this by introducing more stringent requirements for factors such as energy and water consumption, as well as post-construction certification to show whether or not the building lives up to design expectations. On top of this, rewards will be offered for environmental innovations and an “outstanding” category will be introduced (see box, below).It is not just clients and design teams that will be affected by the revamp. It will also be crucial to the future of BREEAM itself as it comes under increasing attack from competitor assessment tools such as LEED, which has stolen a march on the international stage and is well placed to become the international measurement tool of choice.

BRE is also keen for BREEAM to be on the front line when a Code for Sustainable Non-dwellings is developed, particularly after the version of BREEAM for housing – Ecohomes – was adopted as the Code for Sustainable Homes.

“We’re very conscious it could be seen as that,” says Alan Yates, technical director of BREEAM. “The government recognises that BREEAM is there as an internationally leading methodology and it doesn’t make sense to tear that up and start again.”

For many in the industry, BREEAM has been long overdue a revamp. As Clare Howe, sustainability director of environmental consultant Corporation Green, says. “You can get an ‘excellent’ or ‘very good’ rating without going too deeply into issues such as energy. If a site has a location close to transport links it will automatically do quite well.”

It’s a view echoed by Anthony Coumidis, director of environmental and sustainable solutions at McBains Cooper. “The current version isn’t robust enough and doesn’t give the right incentives to do certain things.”

Elements of BREEAM are nonsensical. Unnecessary weighting is given to things such as cycle racks, where you get excessive numbers of points

Tony Defries, Savills

Skewed points

The present system awards points from one to 100 based on environmental criteria. For a building to pass, it must gain 25 points, while an “excellent” rating requires 70. Coumidis points to a recent scheme he worked on where a geothermal system was installed to reduce energy demand at a cost of about £1m. “That got us three points. We then put in measures for the refuse collection and that got us 15. The weighting is disproportionate to the actual benefit to the site,” he says.Others have similar complaints. “There are elements of BREEAM that are nonsensical. Unnecessary weighting is given to things such as cycle racks, where you get excessive numbers of points, which I think devalues the merits of BREEAM,” says Tony Defries, director of Savills Building Consultancy.

BREEAM received a further setback last year when the influential UK Green Building Council (UKGBC), which has the ear of the communities department, debated whether or not to support the outdated system. Last month, a year after the UKGBC was formed, it finally gave its backing to the scheme.

UKGC backing

Paul King, the council’s chief executive, admits that this hesitation was a result of concerns over the current scheme, but says these will be addressed in the new version. Indeed, following last month’s announcement, the UKGBC will work with BRE in its development and promotion.Fundamentally, the changes pick up on the issues that have been adopted in the Code for Sustainable Homes, including targets for waste and materials selection, as well as energy use and water. Pilot projects will begin imminently to finalise what these will be.

Meanwhile, the introduction of post-construction certification aims to answer accusations that the current system is open to abuse by making sure what was promised in the design makes it through to the finished building. “The post-construction review adds that extra element and will make it more credible,” says Corporation Green’s Howe. “In terms of cost, it’s another assessment that has to be carried out.”

The changes to BREEAM are due for launch in May and will come into force in August. Only then will it be known if the upgrades will help it regain some credibility. “It’s tougher but it’s tougher for a good reason,” says Howe. “We certainly need to move forward and the bar needs to be raised.”

The key changes

- The setting of minimum requirements for energy and water consumption

- The introduction of an “outstanding” rating. Currently an “excellent” rating is achieved when a building scores 70% of the potentially available score. “Outstanding” designs will need to achieve 85%

- Post-construction certification. This has previously been an option but it will now be compulsory for every rating

- Innovation. Design teams and clients will be invited to put forward project innovations that will earn them extra credits. The ideas will be vetted at the design stage by a committee to see if it will achieve an environmental benefit. Clients must commit to monitoring the performance of whatever they are innovating and make this public, whether it works or not

- Materials selection. Minimum requirements will be put in place. For example four of the seven key building materials must be rated

A+ to D in the, as yet, unpublished fourth edition of the Green Guide to Building Materials

Downloads

BREEAM rating ideas

Other, Size 0 kb

Postscript

This article was headlined Excellent isn't good enough in Building Magazine on 14/03/2008

For more comment on BREEAM go to blogger Mel Starrs' website

3 Readers' comments