It’s hosting the 2014 World Cup, and the 2016 Olympics, and has emerged from the credit crunch with barely a scratch. So why aren’t more UK firms working there?

You’re on the beach in Rio. You’ve just knocked back your first caipirinha of the day at one of the beach-front drinks stands along Ipanema beach. Beautiful people strut up and down the road in front of you. Maybe you’ll have a quick game of beach volleyball, or maybe a late surf. You may order another drink. In the morning you wake up to go to work on some of the most exciting mega projects the planet has to offer - a World Cup stadium here, or an Olympic sports venue there. Or perhaps the world’s toughest high-speed rail link, which needs to conquer dizzying contours to reach it’s destination. Indeed, you have access to more than £350bn of work, and that’s just in the public sector. In fact, the opportunities in a country that is on course for 6% growth this year and barely noticed the credit crunch are almost unlimited. Interested? Of course. Why wouldn’t you be?

There is little doubt that Brazil is brimming with work for the right company. And it’s never going to be a hard sell to get staff to work there. But it is also beset with difficulties. As quickly as you can count the advantages, the problems present themselves: language, political bureaucracy, a protective regulatory regime and few historic ties to Britain all conspire to make this one hell of a difficult place to break into. The shocking truth is that, despite all the promise that Brazil offers, there is still not a single UK contractor or architect with independent offices there.

Perhaps the greatest problem of all is that the country that built an entire capital city, in Brasília, in the sixties and has probably constructed more large hydro dams than the rest of the world put together, has actually got a pretty mature construction industry of it’s own. The list of those, like Bovis, that have tried and failed to make it is an illustrious one. The firm tried to convert a job building Brazilian branches for its international client, HSBC, into a wider presence in the country in 1997. Fast-forward 13 years, and while technically it still has an office there, it hasn’t had any work in the country since 2005.

So like a medieval chivalric quest that promises riches beyond your wildest dreams if you can overcome obstacles and prove your commitment, only those with bravery and stamina will make it through. So, the question is not so much why not, but do you dare?

The opportunities

It’s worth spending a moment to quantify the potential in the Brazilian market. For a start, in March the government announced the second phase of its accelerated growth plan (PAC), under which it said it would spend 959bn Reais (£359bn) in just three years. The programme includes logistical and social infrastructure, with money to be invested in energy, highways, railways, sanitation, health, education, urban transport and housing, to name just a few. While many are quick to point out that the first 2007-10 phase delivered only half the investment promised, it still involved R257bn of spending.

If the latest phase, constructed around a central government pledge to increase “investment” spending to over 21.5% of GDP, does similarly well, we are still talking about R500bn (£182bn) of construction in three years. Presidential candidate Dilma Rousseff, architect of the PAC, says she wants nothing less than Brazil becoming a full part of the developed world within 10 years.

The first phase of the programme undoubtedly suffered from a degree of bureaucratic inertia, with a lack of hard deadlines to focus the mind. Now, with the World Cup planned for 2014 and the Olympics for 2016, the situation could not be more different. The government is acutely aware that the country’s infrastructure is not fit to host global events of this scale. Spectators will have to be able to get to the venues, media will need reliable communications infrastructure to report from the events, and tourists will need to get into the country using airports capable of handling the traffic. As Jose Bernasconi, director of Sinaenco, the country’s trade body for consultant architects and engineers, says, there is an enormous task to be undertaken. “These events are an unparalleled shop window on the world, a once-in-a-half-century opportunity. If we are not careful the window will be broken when people are looking.”

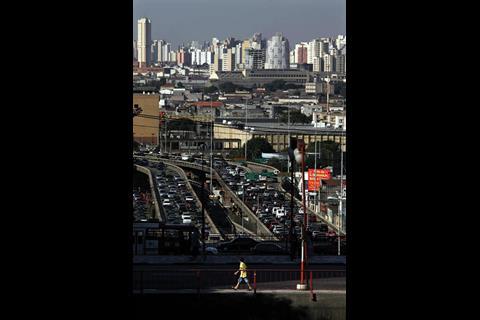

With Brazil’s economic growth showing no signs of abating, the infrastructure problem is approaching crisis levels. Eduardo Parente, chief executive of the country’s largest freight railway, MRS Logista, gives one telling example. “Because of the quality of existing infrastructure, the average speed for one of our rails is four miles per hour. My finance director said to me ’I wouldn’t buy any track if I could walk faster than it.’ It’s a fair point.” Similar stories are told with roads - 90% of Brazil’s roads are unpaved - ports and urban transport, as evidenced by São Paulo’s notorious traffic jams.

And there is similar demand for construction in the private sector. Consultants such as McBains Cooper are avoiding the competitive public programmes and instead focusing on what they see as major opportunities for the building of hotels and private healthcare facilities. According to Valor Economico, Brazil’s leading economic paper, the Brazilian development bank BNDES is to stimulate the market with R1bn (£390m) of loans, with hotel chain Accor alone working up a development pipeline of R1.4bn (£520m).

The catch …

And yet there are real questions for UK companies looking to participate. The first is obvious and unavoidable: the language. Many Brazilians speak a little English, but rarely enough to conduct business in the country. To be successful you will have to be able to converse in Portuguese - end of story.

If that can be overcome, formal bureaucracy is also an issue. To do any business in Brazil, you will have to have a local partner, or set up an office as a Brazilian business. Otherwise it is practically impossible to win work, and any development plans or designs have to be submitted from a Brazilian-registered business for ratification by the federal architecture bodies.

As there is no “double taxation” treaty between the UK and the country, non-locally registered businesses will be taxed both in Brazil (normally at 15%) and when profits are repatriated. So prepare to have to make your prices uncompetitive. As one interested consultant said: “Don’t expect to be able to go in and compete on price. You have to offer something extra.”

The bigger barrier is, however, cultural. Unlike some other fast developing nations, Brazil has no natural inclination to seek outside help, and no particular preference for UK firms (the only slight advantage is not being from the US, as some Brazilians show a traditional Latin American antipathy towards their overbearing northern neighbour).

Santiago Klein, managing director at McBains Cooper International, says: “In Mexico if you’re from the UK they assume you’re great, but in Brazil their attitude is, ’How dare you tell us how to do our job’.” Jon Coxeter-Smith, head of the global sports group at consultant Davis Langdon, which is exploring the possibility of working on Olympic and World Cup-related projects in the country, says: “Appointing a Brazilian firm is the default option. If you came in as some kind of insensitive, imperialist-sounding firm expecting to be appointed, you wouldn’t get far.”

Part of this comes from the fact that Brazil has a huge and sophisticated construction market of its own, as you would expect from a country with 200 million people and the eighth largest economy in the world.

Nigel Peters, project director of British Expertise, says: “You shouldn’t think it’s another Middle East where there’s lots of money but no expertise. There’s a good

self-contained industry there.”

Five key players dominate the market: four contractors - Odebrecht, Camargo Correa, OAS and Andrade Gutierrez - and engineer Concremat. To all intents and purposes the market is sown up between them. As well as presence and experience in Brazil, these players all have very close contacts with the public authorities, and a deep understanding of how the complex political system works. One or other of them are likely to be involved in pretty much every significant contract in the country: don’t expect to be able to go up against them and win.

This makes it very difficult for big contractors to make their mark in the country, as Bovis Lend Lease found to its cost. However, that doesn’t mean there are no opportunities working with those firms. They are aware that they don’t have all the skills or capacity needed to answer all of the demands from Brazil’s construction industry. Augusto Sergio, country manager for Halcrow in Brazil, which has designed the proposed Rio-São Paulo high-speed rail link, says: “Brazil has the most qualified contractors in the world for building dams, but the kind of precision construction, to the tenths of a millimetre, needed for high-speed rail is not yet available.”

Most public sector jobs are procured first by securing a design through a public competition, and then a public design-and-build tender through Brazil’s equivalent of the Official Journal. The ubiquity of design-and-build means that the contractors control the process, usually appointing the rest of the team, so it’s them you need to know. McBains, for example, is exploring the market in partnership with Concremat.

Valeria Martinez works for UK Trade & Investment in the country, and says there is space for UK players outside of straight contracting. For example there are no big Brazilian quantity surveyors, and few big engineering consultants, outside Concremat. “The idea is to find niche opportunities - for example in transport planning, low carbon technology or sustainable design,” she says. “And you should be speaking to the big contractors. Clearly there’s also an appetite for those with experience of working on the London Olympics.”

Those who do brave the move must be prepared to work in a business environment where personal relationships are all-important. This is not to say that Brazil is an unprofessional place to do business, but that friendship and camaraderie is an expected part of deal-making. Numerous meetings are required before a relationship is strong enough to allow a deal. Coxeter-Smith says: “The relationship thing is key, and the culture is very strong. On one side it’s formal and very bureaucratic, but there’s also the informal. Both need to be understood.” It’s important not to confuse the relationship building - which Brazilians are very keen on - with actual deal-making.

Alessandra Almeida-Jones, regional marketing director at Gensler, says: “Brazilians are very open and will share information. But just because you’ve had three meetings don’t think you’ve got a deal. It can take a while to make a decision.”

Having negotiated the regulatory, tax, economic and cultural barriers, there just remains the politics to get over. Getting public projects off the ground here is tremendously difficult. So far, for example, just three contracts for construction or refurbishment of the 12 stadiums needed for the 2014 World Cup have been let, leading to growing concern from Fifa over progress. (It is still possible certain host cities may be abandoned because of an inability to guarantee construction will be completed). The planned high-speed rail link between Rio de Janeiro and the country’s economic capital, São Paulo, remains on the drawing board despite Halcrow’s work to create the design. Partly the delay is caused by problems with the economic viability of the project, but partly it is caused by layers of bureaucracy, and an inability to take decisions in advance of the presidential elections scheduled for October.

Bureaucracy to the power of three

Brazil has three important tiers of government - federal, state and municipal - all of which have different responsibilities, but capital projects often require funding, and therefore decision-making, from all three. Nine of the World Cup stadiums, for example, are the responsibility of municipal governments as they are on city-owned land, but cannot be afforded without federal help. Industry sources said an offer by the government’s development bank, BNDES, to loan them money has not been taken up allegedly because it wanted the builders to guarantee the loan without any control of the asset. The impasse continues.

However, much of the slow progress is also down to concerns over privatisation. Brazil’s economic renaissance of the past decade, based on hard-won political stability, has occurred under a left-wing government run by the charismatic former shoe-shiner and street vendor, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, known as president Lula. The country’s huge poverty problems mean that, unsurprisingly, employment issues are very fraught, and the labour unions - who have been huge supporters of Lula, bitterly oppose anything that smacks of privatisation. So at the same time that the central government recognises there is no way it can hope to fund all of its ambitions without bringing in private capital, it is reluctant to do so, particularly in an election year. One UK engineer, which has just decided to open an office in the country, says: “You have to imagine it’s like the UK before Thatcher. People are very suspicious of private money.”

The example of the airport sector is the most obvious case in point. Infraero is the national agency which owns and runs the airports in Brazil, and the sector is recognised across the board as one that needs tackling urgently before the 2014 World Cup in Rio de Janeiro. (In the same year that BA is reporting record losses, Brazil this year is trying to cope with a 23.6% growth in airport traffic, according to the regulator, Anac - that equates to doubling traffic in just over three years, with facilities already inadequate for current passengers.) The body has plans to redevelop 22 airports and invest R6.5bn (£2.4bn) between 2011 and 2104, but these plans have been gathering dust for years waiting for a decision to be made of how to pay for them. The agency itself is a branch of the military, and hence has never had any interest in growth for commercial gain (hence UK airport architects such as 3D Reid and Pascal Watson are being courted by Infraero and the major contractors for their experience of designing airports to make money).

But there is little chance of getting any work soon. Infraero still says it is planning to market a number of major airport PFI concessions, but all the potential players have been told no decisions will be made until after the election, because such a move would be so controversial. Otavio de Azevedo, chair of contractor Andrade Gutierrez, says: “Something has to be done about airports. The regulation is very precarious and doesn’t allow investment. The government debates what to do but never gets to an end. The demands are huge.”

The airport sector is just one example. Presidential candidate Rousseff admits some culpability of government, but overall says the failure to secure private investment is

not down to bureaucracy. “The Brazilian state will have to be agile, and it isn’t. But Brazil lost the culture of investment. So when we started the PAC people thought it was the

job of the government to provide the money. But government money is not enough; we will have to structure a way to bring in private funds.”

Sinaenco’s Jose Bernasconi sums up the problem for the nation: “Brazil is not a teenager anymore, but sometimes still we daydream. We still have many things to do.”

For anyone looking to enter the market, these words are worth heeding. Brazil: frustrating, bureaucratic, difficult; but marvellous, unparalleled in opportunity and desperately wanting to change. The choice is yours …

If you want to find out more about working in Brazil, key contacts include Valeria Martinez, sector manager for Brazil at UK Trade & Investment, and Nigel Peters, project director for British Expertise.

Valeria.Martinez@fco.gov.uk np@britishexpertise.org

Brazil’s economic miracle

The country has been growing strongly for most of the last decade, on the back of an extended period of political stability, and growing confidence in the country’s future. While growth was flat in 2009, it is predicted to return to boom-time levels of 6% this year and remain at that levels until 2014. Even in the “flat” year of 2009, the economy still created 900,000 jobs, when unemployment rose in most western economies. Indeed the country is so confident that earlier this year it removed measures on tax and interest brought in to stimulate the economy, in order to prevent the economy over-heating.

Much of the growth in the country is on the back of the mining of oil off the coast of Rio, which is being slowly but surely exploited by the giant state/private venture that is Petrobras. Other economic indicators, such as debt, also look very favourable - Brazil’s borrowing this year is 1.5% of GDP compared with 13.5% in the UK. In part it avoided much of the problems of the credit crunch, because so little of the economy was based on credit.

Guido Mantegna, Treasury minister, says: “We are looking now for sustainable economic growth that doesn’t produce debt or inflation. Brazil can now be considered a construction site. It’s a miracle we can meet demand.”

However, there is an elephant in the room: high interest rates. One of the reasons borrowing is so low in the country is because it has always been so expensive. Potential investors need to factor this in to development plans.

Castro Mello’s replay

The opening game of the 2014 World Cup could be an unexpectedly sweet moment for the Castro Mello family.

In 1970 Castro Mello Architects won a commission to design a 110,000-seat national stadium for the country in the gleaming new modernist capital, Brasília. The design, sleek and restrained, yet with echoes of Roman grandeur, was to complement Oscar Niemeyer’s modernist vision for a new type of city.

It was created by the founder of the firm, Brazilian Olympic high jumper Icaro Castro Mello, and his son, Eduardo. However, the vision was never realised. Instead, a limited portion of the stadium was constructed, giving room for just 40,000 people.

But now Eduardo, who has run the practice since the death of his father in 1986, has been recomissioned 40 years later to complete his vision. He is now working with his son, Vincente to make the R900m (£336m) stadium fit for the World Cup in 2014, albeit shy of the original 110,000-seater estimate.

Eduardo says: “It is so exciting the possibility that this will now be complete after all this time.”

The 70,000 seat stadium is also one of the few of the 12 that is going ahead, despite a hiatus recently when the national auditor questioned the cost of the stadium. UK transport consultant Steer Davis Gleave is working on the spectator modelling for the plans. A decision on the contractor is expected on 7 June.

And now, with the São Paulo stadium, which was to be the site for the opening of the Games, experiencing difficulties owing to late Fifa changes to the design regulations, Eduardo is eyeing another opportunity. “I am convinced the opening match will be in Brasília,” he says. “We’re the only place that will have light rail transport and extra facilities, and we are the capital. We can say “this is Brasília” in front of millions of eyes.”

The Rio olympics six years to the starter’s gun

Last month President Lula inaugurated the APO - Brazil’s equivalent of the ODA, which is charged with the $14bn programme to build the venues and infrastructure for the Olympics.

He has put the communist sports minister Orlando Silva in charge of it, and also set up a body to look after sporting legacy. Built across four parts of the city, the government is already talking to the International Olympic Committee about changing its bid, by moving some venues and the media centre to revitalise rundown former dock area of the city.

Brits in brazil

Familiar names who’ve committed to Brazilian offices …

Aecom, Arup, Bovis Lend Lease, Buro Happold, Davis Langdon, Halcrow, McBains Cooper, Steer Davis Gleave

… and others who are dipping their toe in the water

3D Reid, BRE, Foster + Partners, Gensler, Mace, Pascall + Watson, PRP Architects, Space Syntax, Vinci

Downloads

Map showing the key venues for the 2016 Rio Olympics [PDF]

Other, Size 0.28 mbThe World Cup: Four years to kick off [PDF]

Other, Size 0.47 mb

No comments yet