The Building Awards 2018 Refurbishment Winner is a radical build-to-rent scheme that retranslates derelict Victorian terraces for 21st-century living in a way that encourages community, creates space for family living – and provides a blueprint for developers all around the country to copy. Ike Ijeh reviews Welsh Streets

The Housing Market Renewal Initiative may not be one of the more memorable examples of Blairite domestic policy but it remains one of the most controversial. Between 2002 and 2011, what was more commonly known as the Pathfinder programme resulted in the demolition of nearly 20,000 homes in the Midlands and northern England at a public cost of almost £2bn.

The idea was to “renew failing housing markets” in selected deprived areas by demolishing substandard accommodation and replacing it with modern housing that would boost local property values, stimulate economic investment and drive urban regeneration.

The reality all too often became a bizarre dystopian stalemate of half-demolished neighbourhoods severed by a Kafkaesque government policy where homes were essentially being destroyed because they were too cheap. Even worse, we can now tell, albeit with hindsight, that prevailing economic trends over the last decade probably would have seen house prices rise even in deprived areas thereby propelling the kind of market-driven regeneration the government was seeking but with significantly lower recourse to the public purse.

One of the most controversial elements of Pathfinders was the demolition of thousands of Victorian terraced houses, which Pathfinder frequently deemed “unfit for human habitation” but heritage bodies such as Save Britain’s Heritage insisted could be refurbished.

Now, 16 years after Pathfinder was initiated, Save Britain’s Heritage’s claim would appear to have been vindicated by the inspirational refurbishment of a neighbourhood that escaped the Pathfinder axe at the eleventh hour and has now won last week’s Building Awards 2018 refurbishment category. Welsh Streets is the informal collective name given to a series of parallel residential terraced streets in Toxteth, Liverpool. Built in the 1870s by Welsh architect Richard Owens, they were named after and built for some of the estimated 20,000 Welsh builders who helped build booming Victorian Liverpool’s expanding network of public buildings in the 19th century.

But by the late 20th century, Toxteth and its eponymous 1981 riots had become a byword for catastrophic levels of urban deprivation and decline. With its crumbling terraces and acute poverty levels, the neighbourhood became a natural Pathfinder target in the 2000s. Welsh Streets, along with scores of other districts in and around Toxteth were earmarked for demolition.

Brought back to life

In 2010, enthusiasm for Pathfinder had waned and the election of a coalition government more minded to refurbishment than demolition saw the scheme scrapped for good, earning Welsh Streets and its 400 empty homes a reprieve.

Now its Victorian terraces have been lovingly restored and converted back into 299 homes, with further conversions planned in future phases. The redevelopment model is unique. Placefirst is a lettings agency that also acts as a developer and contractor. It purchased the homes, refurbished them and now offers them for short- and long-term let in a rare example of the build-to-rent (BTR) model being applied to existing houses rather than new-build flats.

BTR occupies a relatively small portion of the UK housing market. According to Martin Ellerby, Placefirst’s head of new business and innovation, the BTR rent model is central to the scheme.

“None of this would have been possible without the BTR model. It’s a long-term investment model that doesn’t require the quick return of an immediate sale,” he says. “If we’d bought these houses to refurbish them and sell them on, there’s no way it would have been cost-effective because in that time the land values wouldn’t have increased by a sufficient margin for us to earn our money back.

“The only way private sales could have worked would have been if we’d reduced quality or if we’d been subsidised with government grants, which we definitely weren’t.”

Who lives in Welsh Streets?

Phase one of Welsh Streets was fully let within 24 hours of its market release in August 2017 and almost half of the phase two tenancies have already been reserved off-plan. So what is the secret to Welsh Streets’ success? James and Jess are a young photographer couple who moved into a converted two-bedroom house in Welsh Streets after renting elsewhere in the city. Like many, they are priced out of home ownership for now, but for them, a big attraction of Welsh Streets was the community feel.

“We’ve only been living here a month, but it already feels like home. The communal garden spaces really sold it for us; they are blank spaces which you can really make your own. At our last property the alleyway at the back became a communal dumping ground, but here you have a combination of private and shared space which really encourages you to get to know your neighbours.”

So much so that Jess and James admit to “not having noticed” the removal of the narrow “defensible” strips of front garden that originally lined the terraces, and confirm the wider pavements that now extend to their facade haven’t given them “a problem with privacy at all”.

The development’s heritage was also a big sell. “We were really attracted to the historic detailing and features such as the arched doorways. We also love having a bay window. But the combination with more modern spaces inside worked really well for us, too”. Of these interior spaces, the couple admit being “drawn to the open plan and generous amount of natural light” and maintain that the house is a “perfect size for a couple”.

Size emerges as a key issue and the couple feel reassured that the variety of bedroom sizes offered by Welsh Street properties would enable them to stay in the area even if they need more space in the future. Their final assessments may chime with the aspirations of many young people who often have to choose between affordability and location. “It’s reasonably priced, close to town and in an up-and-coming area. Plus we’re allowed to keep our dog, which is virtually unheard of with tenancy contracts!”

Remodelled for modern life

The quality Ellerby refers to is immediately evident when viewing the refurbished terraces. The restoration is modest yet beautifully executed, with cleaned brickwork, new windows, re-tiled roofs and carefully reconstructed heritage details such as patterned and decorative lintels, staggered corbels, recessed arches. These simple buildings have been treated to a stunning revamp.

It’s difficult to imagine the appalling state of the terraces when work began, until you look at the streets that have yet to be restored. Ellerby recalls their condition. “We faced every kind of problem you could imagine. Damage from water ingress, foundations that needed underpinning, fire damage, subsidence, crumbling chimneys, rot and even bats. When we began, some of these properties had already been empty for 15 years – before Pathfinder.”

Internally, the results are as impressive as outside. All the houses have been renovated to EPC level B or C and reveal neutrally but robustly decorated rooms that are hardwearing enough for the rental market but finished to a standard that would attract both families and the lucrative young professionals market. A key selling point is Toxteth’s close proximity to Liverpool city centre.

Rooms are often surprisingly generous sizes, aided by the general open-plan reconfiguration of the ground floor. While the houses were originally built for low-income families, they still reveal the late-Victorian preoccupation with daylight and ventilation and thereby benefit from bay windows and high ceilings.

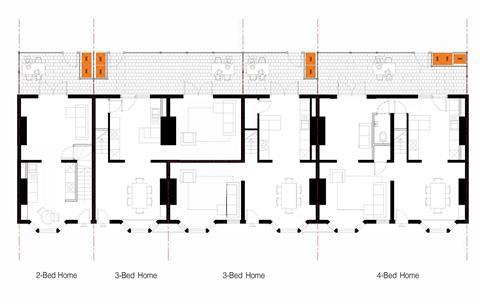

A key feature is the redevelopment’s ingenuity with internal layout. Two-, three- and four-bedroom properties have been created, a variety that has called for some imaginative reconfiguration of building footprints. Some party walls have been knocked through to allow certain rooms to extend into neighbouring plots and create a “scissor plan” of overlapping houses. The alternative would have been a straight refurb of the original houses, which would not have provided the diversity of mix that local demand required, particularly for larger family homes. “It’s much more a remodelling than a refurbishment,” says Ellerby.

While the fronts of the houses remain largely unaltered, the rear facades have been changed radically. The “outrigger” sections of the houses – the narrower rear sections that gave the original houses their L-shaped plans – have been demolished, for two reasons. First, many of the houses were poorly built from the start, which had accelerated their advancing decrepitude over the years. The worst sections of many houses were the outriggers, so the decision was made to demolish them in their entirety. The second reason was to provide vital amenity space for gardens to the rear, where previously there had only been a narrow and wholly inhospitable alleyway snaking between the rows of terraces. Removing the outriggers has allowed for shallow private gardens and, crucially, communal areas for shared use by the residents.

Prioritising community

These rear communal areas are joined by an excellent external works strategy that also sees narrow strips of functionally redundant front gardens removed to widen pavements. The laying of new fibre-optic cabling under the streets and the poor condition of many of the neighbourhood’s trees means that many trees have been removed, but the widened, smoothly landscaped pavements provide the feeling of traversing a boulevard – indicative of the transformative care given to communal areas as well as private ones.

Again, Ellerby says this is symptomatic of the BTR model. “We’re here for the long term. We’re not private developers who sell on and leave; we’re landlords with an active interest in creating an attractive, communal environment where, as well as providing ongoing maintenance, we’re also able to attract tenants who want to be part of a community.”

The concept of community is critical to Welsh Streets’ success. One of the issues regularly ignored when deprived areas are redeveloped is that deprived areas can often foster the most tightly knit communities – something that was previously evident in Toxteth – as elsewhere. A new sense of community cannot be created overnight, but Welsh Streets has provided strong framework for one to flourish.

Accordingly, while Ellerby is happy to admit the project came with its challenges, he maintains that the BTR approach of remodelling rather than demolishing the original terraces “offered a unique blend of old and new that provided the best conditions for a new, 21st-century community to flourish.”

Such is the success of Welsh Streets (see “Who lives in Welsh Streets”, previous page) that it is impossible not to reflect on how close it came to never seeing the light of day if Pathfinder had had its way. By as early as 2007, Pathfinder’s days were numbered, with the Commons Public Accounts Committee savaging the programme as “a disastrous piece of social engineering in which £2.2bn has been spent and 10,000 homes demolished that should have been refurbished. And there is no evidence that anything has been achieved in terms of higher house prices or quality of life for the communities involved.

“We have wasted more than £2bn for nothing.”

Unexpected debt of gratitude

But was it for nothing? While it is easy to look at Welsh Streets as a survivor of the Pathfinder axe that proves the programme was fatally misguided, in an ironic way these homes owe their very existence to the government initiative that set out to destroy them.

“None of this would have been possible without Pathfinder,” says Ellerby. “The long-term investment model of build-to-rent means you need a blank canvas; you can’t deliver it within individual homes or pepperpot BTR units in a meaningful way within an existing fabric.

“Pathfinder gave us that blank canvas because the compulsory relocation of residents it required for demolition ensured all the homes were already empty right from the start.”

If Welsh Streets does owe anything to Pathfinder, it is clearly more by accident than design. But the lessons of Welsh Streets extend far beyond Pathfinder or even the BTR sector. For in developing a simple yet ingenious formula for providing new much-needed rented residential units in derelict buildings, Welsh Streets has set a truly creative, celebratory and inspirational precedent for how affordable, high-quality housing can be delivered as Britain grapples with the housing crisis.

The fact these results have also been achieved in a way that reconnects with local heritage and revitalises struggling communities – conditions widely prevalent elsewhere – means the Welsh Streets formula has triumphed where many have failed and should be urgently prescribed across the entire country.

Project Team

Contractor and cost consultant: Placefirst Construction

Architect: MCAU (homes) / BDP (public realm and landscape)

Structural engineer: Renaissance

Local authority: Liverpool City council

No comments yet