Across the Atlantic lies a land of opportunity with £182bn to invest by 2013, the world’s biggest sporting events to host, and new-found oil. Luke McLeod-Roberts finds adventure - and adversity - in Brazil

Winning work in Brazil: White paper available now

When it comes to big construction opportunities for UK firms, Brazil is still the word on everyone’s lips. With a burgeoning economy, £182bn of public sector work available until 2013 and £34bn worth of stadiums and infrastructure to deliver over the next three years, it is confidently leading the BRIC pack to recession-busting levels of growth.

A year ago Building visited Brazil to find out how UK firms could best crack what is considered to be an exciting, but risky, market. As in any emerging economy, the Brazilian construction and development sectors have their share of hurdles, bureaucracy and a language barrier.

“Foreign companies going it alone will meet a lot of problems,” says Paulo Safady Simao, chief executive of the influential construction lobby group Camara Brasileira da Industria da Construcao (CBIC). “There are companies that have been based here for years and still don’t have any work.”

Twelve months since we visited, however, it is becoming increasingly apparent that it’s well worth getting past the pitfalls.

The Brazilian economy is booming. It grew 7.5% last year and is predicted to grow between 4% and 5% this year. Population growth and a rising middle class are fuelling consumer demand and the government is determined to invest heavily to realise what it believes to be the country’s destiny as a developed country.

In the latest stage of Brazil’s accelerated growth plan, the government pledged to increase investment to over 21.5% GDP - that’s £182bn between 2010 and 2013. Money is being pumped into everything from oil and gas to high-speed rail and, of course, there is the construction of the stadiums for the football World Cup, which the country will host in 2014, and the 2016 Olympic Games, which will take place in Rio de Janeiro.

Building returned to Brazil this year to check out what progress is being made and the latest opportunities for foreign firms.

The games

The World Cup and Olympics projects are undoubtedly Brazil’s most high profile schemes. Work on the two events is worth about £35bn, which should mean plenty of lucrative jobs - but the extent to which British companies can get involved varies.

On the World Cup, UK firms should not expect to pick up main contractor roles. Contracts on all but one of the 12 stadiums - Arena da Baixada in the southern city of Curitiba - have been let out. This doesn’t mean, however, that there’s no work going. Roofing, for example, is one area that may provide opportunities.

“Brazil has never had closed roofs on its football stadiums,” explains Rodrigo Prada, director of Portal da Copa 2014, an initiative of the architects and engineers’ trade association Sinaenco to monitor progress on the World Cup projects. “[Contractors] will all hire foreign companies to do it, if they haven’t already done so.

“It’s an absolutely new area for Brazil. In the case of the Maracana it’s almost half the value of the stadium.”

There may also be work in the product supply chain and in providing infrastructure. Prada says that the civil construction boom is putting constraints on supply. “As well as the World Cup you’ve got the Olympics, the oil, the real estate market, and there’s a problem in a lack of equipment for the sector,” he says.

“Brazil will probably have a lack of tractors, lighting, telecommunications and turf. Components of the turf are probably going to have to be imported from Belgium. Brazil didn’t have factories specialised in making seating for stadiums, so many businesses are buying them abroad.”

In terms of associated infrastructure, Prada explains that there is a need for security specialists and those operating in telecommunications: “Something that Brazil will need - an area in which many British companies specialise - is security. This is essential for a major event and there are immense opportunities because there aren’t businesses that have the know-how on a major event like this - from checking for bombs to identification of people that arrive, speeding up arrivals at the airports. Businesses that have experience in the automisation of security [are required].”

Another sector in which Brazil is a bit behind is telecommunications - in fibre-optic cabling and transmission of data. “It’s an area in which Brazil is importing material,” Prada adds.

However, firms planning to get involved should be aware of the problems affecting the World Cup build programme, which are are an example of the challenges of working in the country.

Costs have increased by R$300m (£116m) on Rio de Janeiro’s Maracana stadium. Elsewhere, disputes about who is going to foot the bill for the event is causing uncertainty.

The privately-owned Arena da Baixada has been perhaps the most striking example of this “overestimation”. Costs there inflated by 60% to R$220m (£85m) after Fifa made demands for structural changes. Its owner, Clube Atletico Paranaense, refused to pay the additional cost. The proposed introduction of changes to municipal laws to allow land title auctions to raise cash, has yet to resolve the issue.

Prada puts the nationwide delays down to a “lack of planning, a lack of centralisation and bureaucracy”. He says this lack of planning is endemic to the country’s public administration, as is the tendency of politicians to think only in terms of the four-year electoral terms.

The lack of centralisation, or as Eduardo Leite, commercial director at Brazil’s second-biggest contractor Camargo Correa puts it, “a centralisation of power and a decentralisation of responsibility”, is related to the country’s political system, which has three levels of government: federal, state and municipal.

The decision to host the World Cup across 12 cities - in order to spread the legacy - has also resulted in the worst aspects of this “decentralisation of responsibility” coming to the fore. Bureaucracy affects all aspects of public life in the country, and has given rise to the Brazilian idiom “dar um jeito” (or “finding a way round”).

As a result, engaging directly with the public sector can be a daunting task for international firms going it alone. “It’s a waste of money and energy that is not rational,” comments Leite. “It’s better for international companies to deal [directly] with the private sector.”

Prada, however, thinks that the World Cup could mark a turning point: “Brazil needs a change in planning and management [of projects]. The World Cup could be a catalyst for this.”

Fortunately for the country, there will be a trial run before the main event. “In 2013 Brazil will host the Confederations Cup [for which the previous World Cup winner and the champions of each continent come together for a play-off],” says Simao. “It will be a litmus test for 2014.”

The good news is, however, that all signs so far point to the Olympics being a more streamlined event. The fact that it’s taking place in one city rather than 12 eradicates some of the administrative difficulties.

Furthermore, it has a central body overseeing the project - the Autoridade Publica Olimpica (APO), which is seen as being modelled on London 2012’s Olympic Delivery Authority.

The appointment by Brazilian president Dilma Rousseff of former central bank governor Henrique Meirelles to run the body has generally been viewed as a wise move, given his apparent probity and apolitical approach in his previous role.

And while the construction contracts for the World Cup went to the largest five Brazilian contractors, the masterplan for the Olympic village will go out to global tender - a decision that can only be positive for international hopefuls.

As such, the first opportunity for UK firms will be getting in on the design of the village. Unlike some other public tenders, quality and technical specification will take precedence over cost. Thereafter, there will be jobs for project managers to integrate design and construction. Firms with specific experience on the London 2012 Olympics are expected to have a head start, particularly those with sustainability, legacy and security know-how.

Transport

The scale of investment in Brazil does not end with the world’s biggest sporting events.

“We’re not building Brazil because of the World Cup or the Olympics,” says Renato Giusti, a former director at the major Brazilian conglomerate Votorantim and chief executive of Associacao Brasileira de Cimento Portland, a cement industry trade association. “These projects fell in the middle of the path. We want a [better] Brazil for Brazilians.”

Ricardo Teixeira, president of the Brazilian football confederation, is quoted as saying that the “three major problems that Brazil has for the 2014 World Cup are airports, airports and airports”.

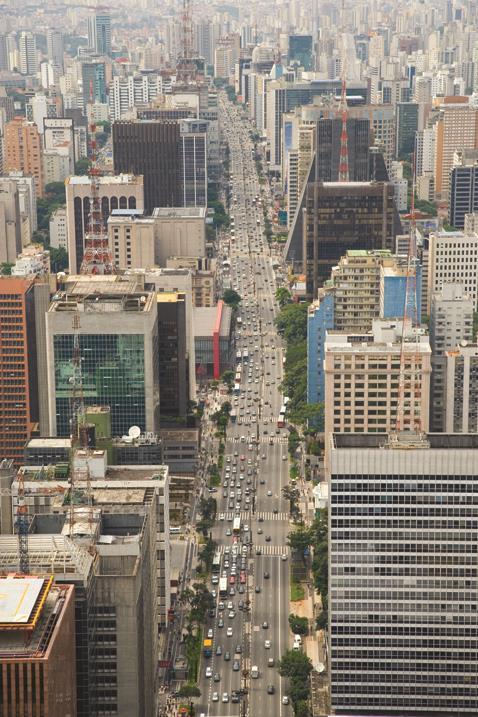

Indeed, Brazil’s struggling airports system may prove to be a major challenge to upgrade. Flying into Brazil’s biggest, Guarulhos on the edge of Sao Paulo, is already not a pleasant experience. The drab, seventies brown-toned interior may be tolerable if you prize function over form. But it is hard to excuse the lack of basic amenities, such as cafes or bookshops.

Then there are the endless queues, caused by the fact that the airport is operating at 57% overcapacity. The lines of people snaking through immigration, baggage collection and customs meant it took Building three hours to get from the plane to the taxi.

The influx of visitors during the football championship is expected temporarily to exacerbate this already serious problem, increasing the number of passengers by an additional 10%.

This situation is unsurprising. Increased competition on air fares and greater disposable incomes in the country - which is the fifth largest in the world by area - has created an annual average growth rate in passenger numbers of 10% each year over the past eight years. In 2010, the rise was 20%.

Last year, Building reported that plans by national airports operator Infraero to invest R$6.4bn (£2.5bn) by 2014 had been “gathering dust for years”. One year on, and you would now have to employ some pretty heavy plant to excavate the plans from the dust drifts.

In the lead up to 2014, it looks like Infraero may have to issue emergency contract awards and resort to short-term solutions such as the construction of prefabricated terminal structures in order to meet the immediate need.

This is not a proper solution, says Simao of CBIC. He believes that the government’s record on this front is its “big failure”. The privatisation of the publicly-owned airport operator Infraero has been mooted for some time, but it is thought that the previous government sidestepped the issue for fear of antagonising the unions.

“Under [former president] Lula da Silva the issue wasn’t resolved,” says infrastructure specialist Marcio Monteiro Reis, from law firm Siqueira Campos Advogados.”There’s a deficient capacity for the demand that exists and the lack of a regulatory framework.”

However, the arrival of new president Rousseff at the beginning of this year may herald some change on this front. One of the first initiatives her government took was to create the Secretariat of Civil Aviation - a department with ministerial status reporting directly to the president - to co-ordinate the various and often competing interests in the sector.

“Everything indicates that there has been a decision to privatise some airports,” says Monteiro.

A pilot project is also underway to build, operate and maintain a new airport on the outskirts of the city of Natal. As well as being a tourist centre and gateway to the palm-fringed beaches of the north-east, it is also situated at one of the eastern-most extremities of the country, so its relative proximity to Europe compared with Rio de Janeiro or Sao Paulo means it could act as a hub for passengers arriving from Europe.

Consultant Ernst & Young was part of a consortium that was charged with developing feasibility, economic and environmental studies for the scheme and to structure the concession agreement. A winner is expected to be announced in July.

As for Sao Paulo’s Guarulhos, construction of a third terminal is still at design phase.

If investments are not made in time to create a speedy connecting route between Brazil’s hub, Guarulhos, and its counterpart airport Galeao, in Rio de Janeiro, then there is another transport possibility to get you to the Games - high-speed rail.

This - in a country largely lacking in passenger rail services - could prove to be a major opportunity for foreign construction firms.

Halcrow is advising the government on technical aspects of the procurement process for a project to cut what is now a five-hour bus journey to a 94-minute train journey.

A year ago, this project hadn’t even got off the drawing board. And a contractor is still yet to be appointed - the project has been put back and will now not meet the original 2014 deadline. However, submission of tender documents is due this month. Furthermore, a company has been established to manage the process and public finance has been guaranteed for the project, although specific sums have not been announced.

Steve Lowry, director of project delivery for the Americas at Halcrow, says: “High-speed rail is being looked at in all Latin American countries, but there’s a greater commitment here than elsewhere. We feel more comfortable on the timing of high-speed rail here because of the speed and efficiency of Brazilian construction companies.”

That isn’t to say that overseas firms won’t get a look-in. In fact, the lack of previous domestic expertise in this area means that there is likely to be a role for companies from countries with a strong history of delivering high-speed rail to provide future technical advice and engineering expertise.

In the long term, the country hopes that high-speed rail could involve considerable transfer of knowledge, skills and technology.

“From a technical point of view, the Brazilian government thinks that the project could be a separation of the men from the boys for Brazilian engineers in terms of expertise,” says Augusto Sergio Guimaraes, Halcrow’s managing director for institutional development in Brazil.

Oil

Brazil is a net exporter of oil, but it is far from producing the kind of yields of, for example, the Middle East. The real game-changer, though, came in 2007 with the discovery of oil, about 300km off the coast of Rio de Janeiro, in a “pre-salt” layer of the sea bed.

Owing to the depth of these fields - in some cases they are up to 7km below the surface of the ocean - the oil contained in them is very expensive to extract, but it is also regarded as being extremely high quality. Plus, there is lots of it. The first field alone - Tupi - is expected to increase national oil production by 70%. Brazil’s left-of-centre federal government may well wish to use that money for the long-term benefit of the country.

“There’s a sense that the Brazilian government sees this as something that will make Brazil a superpower,” says Renato Cordeiro, commercial manager for oil and gas at UK Trade & Investment Brazil. New legislation has been created specifically for the pre-salt zones that gives a greater share of profits to the Brazilian government than on other fields. There are plans to create an education fund from the proceeds.

While the conditions for the private sector may be more onerous than in other oil fields, Cordeiro insists there are opportunities for UK firms to get added value: “In sub-sea technology, Aberdeen-based companies have a lot of expertise. [In] everything related to high pressure and low temperature, UK companies can compete,” he says.

Dealing with state oil company Petrobras can be challenging. To do so companies have to go through a lengthy registration process. But legislation requires its involvement in the pre-salt projects and between now and 2014 it has overall planned investments of US$224bn (£140bn), compared with less than a fifth of that for the private sector.

Housing

Drive in to Rio de Janeiro from the city’s international airport, Galeao, and the usual view of the extensive shanty towns, or “favelas”, lining the hills either side of the road is now obscured by hoardings, resembling the noise reduction barriers that line some European highways. Ricardo, a taxi driver, thinks there may be another reason: “I think the real reason is to hide the favelas.”

But money is also being spent improving security, basic sanitation and basic urbanisation within these communities. The federal government is also spending in the region of £27.5bn on the construction of new housing for the low-income sector via its national My House My Life programme.

While the construction work on this and other urbanisation and real estate projects tends to be carried out by domestic contractors, there are opportunities for project managers based overseas and there’s an increasing interest in developing the sustainable practices that have become de rigueur in the UK, France or the US.

The situation in the housing sector mirrors that in the sports, transport and oil and gas sectors - domestic contractors will take a lead but international contractors are welcome where they enter in partnership with their local counterparts and contribute specialised knowledge lacking locally. But in the long term, Brazil’s ambition to become a developed market means that it wants to source specialised expertise from within its own borders. There may not be much time left - get in there while you can.

How to crack Brazil

Building’s white paper on the Brazilian market is now available to download, provding need-to-know data on clients and projects, and exclusive inforamtion on attitudes to UK firms. Purchase the White Paper here

Brazil in numbers

Population: 193m

Population growth rate (1998-2010): 1.3%

GDP (2010 millions): $2,090

GDP per capita (2010): $10,813

GDP growth rate (2010): 7.5%

Forecast annual GDP growth rate (average 2010-2022): 5%

Value of construction sector (2008):

R$159bn (£62bn)

Forecast annual growth rate in construction sector (2009-2022): 6.1%

Sources: Central Bank of Brazil, FIESP, IBGE, CBIC

CONCRETE SHOW: 31 August to 2 September

The Concrete Show South America is an international meeting point of business and technology, exclusive for concrete supply chain and

its users.

The trade show will be attended by thousands of construction professionals from all over the world gathering in Sao Paulo to do business.

This year Concrete Show South America promises to be an even larger and better show with the best and new technologies in machineries, equipment, commercial construction products, services and constructive systems from leading industry suppliers.

For more information, visit www.concreteshow.com.br/en/

No comments yet