Marks Barfield’s Michael Tippett school – London’s first Building Schools for the Future project – succeeds by ignoring many of the guidelines on both design and procurement. There’s probably a lesson in that, reckons Martin Spring

This is such an improvement on the mean-spirited, mean-windowed schools built under PFI. Walk into the double-height entrance lobby of the new Michael Tippett school in Lambeth, south London, and a wall of glass immediately beckons you, moth-like, to a light, spacious park on the other side. You almost drift past the reception desk in your hurry to get there. Is going to school supposed to feel like this?

The Michael Tippett school is the first school in London to be completed under the government’s Building Schools for the Future (BSF) programme. Designed by London Eye architect Marks Barfield, the £7m building is a secondary school for 80 special needs students, several of them severely autistic. But all schools should heed its lesson.

To achieve the effect for the entrance lobby, the architect had to interpret the school building guidelines rather broadly. It’s supposed to be a library. When I ask where all the books are, architect Julia Barfield says: “We were creative with the brief. The library designation gives us the double-height space.”

Really it’s a social hub, casually furnished with tables and comfy chairs. The school’s head, Jan Stogdon, chips in that in the digital age, traditional libraries are no longer necessary.

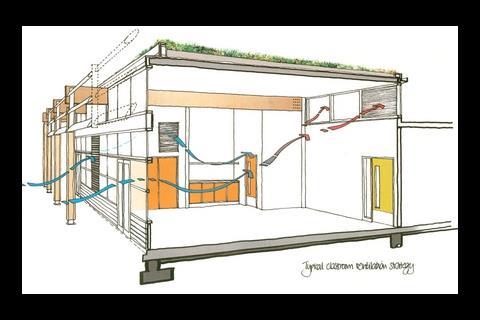

The classrooms are even airier and lighter. Instead of the standard ceiling at a height of 2.7m, each one opens up into an airy void lit by clerestory windows front and back. The glazing continues across the entire external wall and down to a low sill, giving unrestricted views.

Stogdon is clearly relieved: “We were absolutely determined not to have low ceilings like our previous school.”

Visibility is the main idea here. The views out are uplifting, but internal lines of vision are essential too so staff can see what’s going on. “The previous school was full of nooks and crannies which was a nightmare to supervise,” Stogdon says.

People can also look in. The two-storey wing building comes hard up against the pavement on one side and ends in a sharp corner at the road intersection. “We wanted the school to be prominent,” says Stogdon. “Many students like uttering shrieks and wails, and if they are hidden behind a school wall, passers-by wonder what’s going on.”

To achieve the effect for the lobby, the architect had to interpret the school building guidelines rather broadly. It’s supposed to be a library

The building is easy to navigate as well. The main wayfinding ploy was the most basic in the book – colour-coding the doors to denote toilets, classrooms and staff rooms. “Everyone finds their way to the loo,” Stogdon says. Students are also encouraged to use staircases rather than lifts, even though it’s tougher for some. “We want students to become adapted to real adult life and look after themselves without high-tech remote control devices,” she says.

The form of the mainly two-storey school is not in itself compelling: your basic strip of rooms either side of a corridor, with a couple of kinks along its length. After considering 21 options, the kinked layout was selected because of the useful external spaces it created (see site plan below). On the entrance side, there’s a drop-off point for school buses and teacher car parking. On the other, there’s a private play area, landscaped into an attractive mini-park.

The sharp apex of the building encloses two attractive angular spaces with large windows along one side. They both serve as social spaces – the dining hall on the ground floor and the sixth-form common room upstairs.

Outside, free-standing laminated-timber columns spanned by vividly coloured metal louvres give the school its bright, cheery character. The louvres shade the ambitiously glazed classrooms while the columns hold up laminated-timber beams which, in turn, support flat, sedum-planted roofs.

The columns are not just a pretty face, however. They bring a longer-term practical benefit – adaptability. As the external walls and internal partitions have been disengaged from the structural frame, they can be relatively easily changed in the future.

“One of the main requirements for a school like this is flexibility,” says Stogdon. “We can never predict what sort of students we’ll be getting from year to year and what their particular needs will be.”

If schools are about encouraging learning and development, they can’t be oppressive and dispiriting. Stogdon clearly feels this one works. “We have an extraordinary range of students, some vulnerable, some difficult, and none have found this building intimidating because of its light and spacious feel.”

Project team

Client Lambeth council

Architect Marks Barfield

Structural and services engineer Gifford

Quantity surveyor Dobson White Boulcott

Project manager Precept

Landscape architect Edward Hutchison Landscape Architects

Design-and-build contractor Apollo Education

How to build a BSF project on time and to budget …

To become the first Building Schools for the Future project in London to reach completion, the Michael Tippett school in Lambeth was developed in record time. In fact, pupils moved in in February, 21 months after the design was commissioned from Marks Barfield, 16 months since Apollo Education was contracted to build it and just nine months after it started work on site.

They had to move fast because the new school is a combination of two old ones and, to build it, one had to close.

Lambeth council abandoned the normal, lengthy BSF procurement route of inviting competitive design and development bids from two or more consortiums. Instead, it reverted to the old way – appointing the architect on the strength of a competitive interview and,

when the design had been worked up to RIBA stage D, put it out to a two-stage tender for a lump-sum contract, in this case JCT 2005 design-and-build.

The tender included two other schools that had also been pre-designed by architects appointed directly by the council. As Richard Dobson, partner of QS Dobson White Boulcott, says, the schools were let as three separate contracts because of the variety of designs, but awarded to a single contractor for £22m. “There were management efficiencies from dealing with one contractor rather than three, and this led to cost savings,” he said.

It was quick, but that did not mean that the client was throwing money at it. Dobson says it cost about £2,100/m2, within Lambeth’s budget, and within 5% of the Department for Education and Skills’ guidelines published in 2001 (adjusted for inflation, inner London location and special education provisions).

All this, and it eats official design guidelines for headroom, light and adaptability for lunch. Dobson admits though that the design went through extensive value-engineering and the attractive features were kept only by sacrificing others. The most important cost-saver was to stack the building over two storeys. Even so, Marks Barfield managed to keep the extra height of the classrooms by putting them on the single-storey wing and the upper floor.

The school manages to tick all the right boxes – inspired design, ulta-rapid development and affordability. How? Well, Richard Dobson says the incentive to open the first BSF project in London was compelling. Julia Barfield says it was Apollo’s first major school project, so it wanted to do it right and hired good managers to do it.

The client, Mike Pocock, who runs Lambeth’s BSF programme, says the design team worked closely with the school at just the right stage.

Apollo got some other basic things right, too. Daren Moseley, its operations director, says that although the architect and structural engineer Gifford were not novated to Apollo, they were kept on anyway to avoid a time-consuming switch of design firms. Also, the elaborate structural frame of laminated timber, made in Germany, was assembled on site by Apollo’s direct labour force.

So, will Pocock use the good old ways for the other schools in his BSF programme? No. “Our preferred route is to have integrated teams of designers and contractors working together from the start, and then choosing the better of two competing design-development bids. This gives us greater cost and programme certainty. It wasn’t an option on the Michael Tippett school because of the shortened time scale, but the procurement route we used there increased risk.”

Okay, but in all cases? What drove the rapid development of Michael Tippett school was the need for one of its two predecessor schools to release its site for a new building for yet another BSF school. Given that BSF requires all secondary schools in England to be rebuilt and refurbished over the next 15 years, the Michael Tippett scenario will surely come up again. And as this project shows, a traditional procurement route can deliver quality quickly without breaking the bank.

Downloads

Ground floor plan

Other, Size 0 kb

No comments yet