It doesn’t bode well. The first venue to be completed for the 2012 Olympics should have been a regeneration triumph, but instead the sailing facilities on the Dorset island of Portland have sparked resentment among the locals and a grudge against a neighbouring town. Michael Willoughby headed to the south coast to find out why, while Tim Foster photographed the island and the islanders

There used to be four pubs at Castletown standing shoulder to shoulder on the seafront, offering shelter and refreshment to generations of sailors, smugglers, wreckers and other less exotic visitors to the Isle of Portland. On the afternoon that Building visits, the Royal Breakwater Hotel is the only one showing any signs of life.

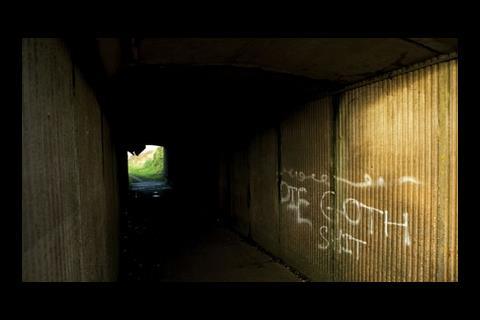

Inside the quiet lounge bar of the Royal, Tracy Harm is pulling a pint. “If there’s ever anything good happening,” she says, “they say it’s in Weymouth. If something bad happens, like someone drowning in the bay, it’s in Portland. When all’s said and done, will we be left with just a load of empty buildings for people to vandalise?”

The casual drinker may fail to realise from Harm’s question that those buildings should be a cause for celebration. Tomorrow, just down the road from Castletown, the Olympic Delivery Authority’s (ODA) £6m upgrade of the Weymouth and Portland National Sailing Academy will be declared open – the first 2012 venue to be completed.

However, as Harm suggests, many Portlanders feel disconnected from the conspicuous wealth of the sailing venue – which is part of the wider £30m Osprey Quay marina redevelopment – and that resentment has revived an old rivalry with neighbouring town Weymouth. Down on the Dorset coast, 130 miles from east London, the ODA is discovering yet more ways for the Olympic regeneration legacy to cause it problems …

The Weymouth land grab

Even before the present downturn, business was not good in Castletown. The real blow came in 1995, when the Royal Navy closed its Osprey base and retreated to Plymouth, taking 4,300 jobs with it. These days, the main industry seems to be running prisons.

It is easy to see why Portlanders might feel riled by Weymouth, all candy-coloured three-storey Georgian houses, bow-fronted hotels and tea shops, just across the bay.

The islanders feel that Weymouth has stolen their chance for regeneration, firstly by shifting focus from the island as a whole to the part closest to the mainland, leaving neighbourhoods such as the (ironically named) Fortuneswell unchanged. And secondly by going on to claim that the area in question is somehow part of Weymouth.

As evidence of the latter complaint, some are pointing to Weymouth’s attempt to grab the northern tip of the island. “Once everything this side of the ferry bridge was considered to be Portland,” says Gus Hoyt, a local whose family have lived on the island for two generations. “The oil tanks and the naval base were definitely not claimed as part of Weymouth because they were too ugly. But now they’ve gone, what’s replaced them has suddenly become the Weymouth and Portland National Sailing Academy.”

Notwithstanding the suspected encroachment of Weymouth, the locals had still hoped that the arrival of the Olympics would help their isolated community. Sebastian Coe, chairman of the London 2012 Organising Committee, said the scheme would “transform Weymouth and Portland into a world-class training and competition venue equipped to stage major international sailing events before and after the 2012 Olympics. This will leave a legacy of elite and recreational sailing for future generations.”

The islanders beg to differ. Anne Alcock, vessel services manager for Portland Bay, says: “The investment in the harbour is fantastic, but just up the road you have Fortuneswell, which is the second-most deprived area in west Dorset. We need regeneration in both areas.”

We’re a bloody mess on the Olympics’ doorstep. There are empty properties falling down all over the place.

John Nash, Portland Stone

Harm says there are plenty of genuine improvements that could have been made for the Olympics that would really have made a difference to lives of the 13,000 people who live on Portland, such as a road around the south of the island. The sole transport improvement that most islanders notice is the traffic calming roundabout that the South West Regional Development Agency (SWRDA) has installed near Victoria Square, where the traffic-clogged, two-lane A354 from the mainland meets the island. SWRDA’s John Ray is delighted by how it slows down boy racers; others complain that it makes their half-hour struggle to get to or from the mainland even worse. Weymouth, on the other hand, is to receive an £80m improvement to the four-mile road from Dorchester and more frequent train services. Portland doesn’t even have a train station.

If you talk to more Portlanders, the individual voices swell into a chorus of complaint. Councillor John Nash, owner of Portland Stone, says: “We’re a bloody mess on the Olympics’ doorstep. There are empty properties falling down all over the place. It’s as though we don’t exist.” Greengrocer John Smith says he doesn’t think Portlanders will really gain anything from the development down at the quay (see box, overleaf). “We won’t benefit on the island,” he says. “It’s no good for us.”

Meanwhile, parts of genteel Weymouth are being improved, including a £6.6m “facelift” for its esplanade …

Do they have a point?

How justified are the Portlanders in feeling hard done by? Jackie Gisborne, head of PR for Weymouth and Portland council, and an islander herself, says Portland been in a glum mood ever since the navy left. “It’s a fact of life that Portland has felt the poor relative to Weymouth,” she says.

Gisborne accepts that Portland’s road network could be improved, but she says that is not as easy as islanders seem to think, not least because of their own obstructiveness. At present Portland has only one supermarket, but on the day Building visited, the villagers of Easton, in the south of the island, were meeting to battle the opening of a Tesco. Similarly, the remediation of the navy’s old oil tanks at Osprey Quay was interrupted by a local group trying to claim them as local landmarks.

Gisborne says: “There has been a huge amount of investment in the island as well as Weymouth. Portland has a bright future. From the catalyst of the Games, we are trying to leave a legacy and Portland is very much included in that. Together, Weymouth and Portland can proudly look forward to a bright future.”

An ODA spokesperson adds that the regeneration benefits are already being felt beyond the sailing community: “The ODA’s works have had a positive impact on Portland, with a large amount of local Portland stone used during the construction works. The new commercial marina being built is a good example of the economic benefits that will boost the island before, during and long after 2012.”

Ralph Luck, director of property for the ODA, who brokered the complicated land deals needed to get the Olympic project off the ground, points out that there are also the Games themselves. “There are going to be five courses – one actually in Portland Harbour and four outside within Weymouth Bay and stretching back along the Dorset coast back to Poole and Lulworth Cove.” However, he adds that sailing is not really a sport that can be watched directly. As such, he says, big screens on Weymouth beach will be the main way of viewing the event.

Anyway, given that the event takes place at sea, the true host is neither Portland nor Weymouth, but the Crown Estate. Will that stop Portlanders feeling they’ve been passed over by the Olympics and the regeneration it promised? Not a chance. “There’s a saying you can’t get blood from a stone,” islander Richard Paveley, says: “Well, Weymouth has always been trying to prove it wrong.”

But while the main residential parts of Portland – Easton, Weston, Fortuneswell – may not see much direct regeneration, SWRDA has undoubtedly pulled off the kind of coup other RDAs would be keen to emulate. To find out whether the islanders’ dark suspicions are realised, we will have to come back to Castletown a few years after the Games – and count the pubs.

Postscript

For more on the countdown to the Olympics, go to www.building.co.uk/2012

Original print headline 'Portland bile'

No comments yet