Charrettes are the new face of collaborative planning, bringing together artists, architects and town planners to thrash out a development plan for an area. But do they work?

Nine o’clock on a Friday morning and the Creekside Environmental Centre in down-at-heel Deptford in south-east London is buzzing with activity. In a room normally set aside for teaching children about local wildlife, a group of architects, sustainability advisers, cost consultants, transport specialists and model makers are busy at impromptu workstations.

With eight hours to go they are putting the finishing touches on a 10-year development plan for 53 sites sandwiching this mile-long tributary of the Thames. What’s most surprising is that it has taken just four days to get to this stage using a new approach to collaborative planning – the charrette.

If you’re unfamiliar with this word you’re not alone. According to Lynne Ceeney, associate director of sustainable communities at BRE, who is overseeing the exercise, it is another of those unhelpful phrases, such as sustainability or amenity. The best way to describe it is as a intensive collaborative planning exercise that brings people together and asks them to come up with a development plan for an area.

So what brings this new-fangled approach to Deptford, of all places? The driving force behind it is Andrew Carmichael, director of creative process at the regeneration body Creative Lewisham Agency. According to Carmichael, a resident and former artist in the area, the stretch of land running either side of Deptford Creek is under huge pressure for redevelopment. This in itself is no bad thing, but Carmichael says with the current planning process there is little opportunity for people to talk about how to create a community. “There were a lot of building projects coming forward, but there didn’t seem to be a forum for people to talk about how to make a place, rather than just a series of discrete developments.”

Carmichael was also concerned that an area frequented by light industry and artists would get blown away. “It would become another Hoxton, where it still has an artistic caché but there are no artists left,” he says.

Deptford could have become another Hoxton, where it still has an artistic cache, but there are no artists left

Andrew Carmichael, Creative Lewisham Agency

As charrettes go, what’s happening in Deptford is slightly different from the traditional format. “It’s a bit of a hybrid because we don’t own any of the sites,” says Ceeney. “Normally they are driven by the person who owns the site or has jurisdiction over it, although increasingly they are seen as a multi-party decision.”

Funding for this initiative has come from a £50,000 grant from the London Development Agency, with further money from landowners and developers. Some of them saw the benefit straight away and got right behind it, says Carmichael. “The selling point for them is that it does help with planning. Also, a lot of this comes down to how well the spaces work and shaping the public realm, and that adds value to their sites.”

In all, 24 people have been employed in the five-day process, all of whom met for the first time on Monday. Although this intensive period is the nub of the charrette, work began six months earlier with the drawing up a list of who owns the land and a history of the planning applications.

So how big an influence can the process have? Of the 53 freehold sites little can be done to make changes to those already with planning or coming out of the ground, but about 70% of the sites are still at a stage where their design can be influenced, and it is these that are being targeted.

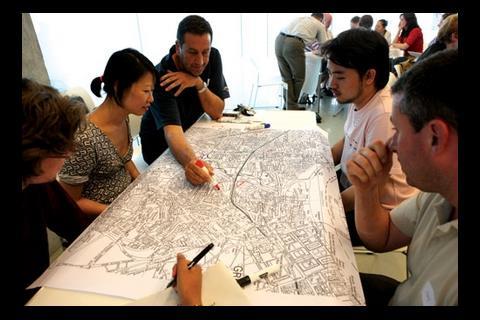

The week has been structured around a series of public meetings and workshops, the aim of which has been to elicit information from local residents, workers and businesses on how they use the area and what they think about it. The evidence of some of these sessions is fighting for space on the walls in the form of hastily annotated drawings and colourful maps highlighting the routes people take to get around. “It’s no good asking people who aren’t designers to design a town,” says Ceeney. “But if you ask them how they use it, you learn a lot.”

If you are a council, everyone expects you to deliver the plan, but because this is being run by a third party, it takes that difficulty away.

Lynne Ceeney, BRE

Armed with this information, the team began to draw up a plan for the area that would tie the sites together, providing developments with a mix of uses and a way of getting around the area. “This process would normally take six months,” says architect Adam Brown. “It’s a time-efficient way of doing it and getting all these stakeholders involved.” Over the five days this design is reviewed and refined.

This might sound slightly woolly but Chris Lloyd of A-Z Urban Studio has been looking at the feasibility along the way. “We want to make sure that anything that emerges is broadly deliverable,” he says. Because of the timescale involved, instead of coming up with a design and testing it for feasibility Lloyd first looked at what the end value needed to be for a site and what volumes of building were needed to realise this. This information directly informs the architecture, and the design is followed up with a more detailed costing, although Lloyd admits there are a lot of assumptions and no talk of timeframes.

The team will come away with a fairly definitive plan of what they think should be done and how it will work. Included in this will be a sustainability strategy. As Ceeney points out, if you want to introduce a local heat and power network, this is the stage at which you need to plan. They will then have another three months to go out and advocate the plan.

Clearly the big question is, with no jurisdiction over the individual sites, how can the proposed plan ever be made to work? In part it will rely on the developers and landowners signing up to the final vision – in the final public meeting about 90% of the stakeholders involved did. Design for London is also talking about creating an opportunity planning framework, and Lewisham and Greenwich councils have commissioned special planning guidance which will aim to incorporate the work done in the charrette.

As Ceeney points out, there is a danger with this process that you build up an expectation. “We have to be careful to say we are shaping what people are doing and we want them to buy in. If you are a council everyone expects you to deliver it, but because this is being run by a third party, it takes that difficulty away.”

Lewisham councillor Heidi Alexander is hopeful. “There needs to be a conversation between the local authority in terms of what the authority recognises is good in this area, what it thinks are the challenges and problems, how you want to shape the future of this area and how you get your benefits out of it in terms of jobs, new homes and improvements to the environment. Hopefully, you’ve got more chance of this happening with the discussion starting earlier.”

What is a charrette?

These days the word charrette is used to describe the process that brings clients, design teams and stakeholders together at the beginning of a project – be it an affordable housing scheme or a community masterplan – to consider the design options open to them and create a feasible plan that meets the needs of all parties.

The process was pioneered in the US 20 years ago and is increasingly being used in the UK. It is particularly effective where developments will have a big community impact and where stakeholders from the public, planning authorities and local businesses can be involved.

The process involves facilitated discussions during which ideas are thrashed out, options agreed, and targets set for issues such as sustainability, renewable technology, specification, community integration and security.

The National Charrette Institute in the US says a charrette has to last at least four consecutive days. This is to accommodate a series of feedback loops, where a design is created and then reviewed and refined at least three times.

A week in the life of a charrette

Monday

- The team meets for the first time

- Focus groups discuss the use of the creek, the creative industries in the area and “hard to reach” community members

- One-to-one sessions with the Environment Agency and other key stakeholders take place

- The first public meeting with an introductory presentation, followed by two workshops to explore what people do in “24 hours in Creekside” and “what will Creekside be like in 2018”?

Tuesday

- Morning Creek walk at low tide to find out more about the area

- Workshops with local faith group and school

- Designing and concept development

- Focus groups on sustainability

- One-to-one sessions with key stakeholders

Wednesday

- Designing and concept development

- Further sessions with key stakeholders

- Open-house public event at Lewisham college, where the designs and ideas are presented and the team is available for questions and discussion

Thursday

- Design team meeting with Design for London and Lewisham planning department

- Plan synthesis and development

- Technical reviews

Friday

- Production of the final visions

- Public meeting at the Greenwich picture house

- Report back and concept presentation

- Discussion and feedback

- Vision statement sign-up

Downloads

Map of freeholds

Other, Size 0 kb

Postscript

Original print headline 'We did it our way'

No comments yet