The Builder reports on the development of a vast new wave of housing to replace the homes destroyed by wartime bombing

The New Towns were a series of planned settlements across England built in the immediate post-Second World War years. Located primarily in a ring around London beyond the green belt, they aimed to address a severe housing shortage caused partly by the destruction of homes in the capital by wartime bombing.

It was also a response to the more than four million soldiers who returned at the end of the war, an influx which created one of the biggest civilian challenges facing the post-war Labour government.

Below are two leader pieces in The Builder covering the development of the New Towns policy. The first follows a speech by Aneurin “Nye” Bevan, one of the chief architects of the welfare state under Clement Atlee, on the government’s proposal –heavily criticised by The Builder – of putting local authorities in charge of increasing housing supply. The second covers the final report by John Reith, chair of the New Towns Commission which was set up to consider how the programme should be implemented.

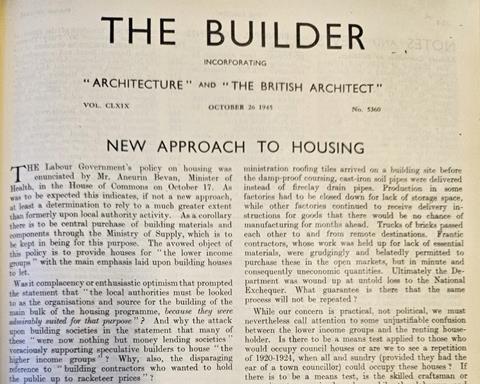

Leader, 26 October 1945

NEW APPROACH TO HOUSING

THE Labour Government’s policy on housing was enunciated by Mr. Aneurin Bevan, Minister of Health, in the House of Commons on October 17. As was to be expected this indicates, if not a new approach, at least a determination to rely to a much greater extent than formerly upon local authority activity. As a corollary there is to be central purchase of building materials and components through the Ministry of Supply, which is to be kept in being for this purpose. The avowed object of this policy is to provide houses for “the lower income groups” with the main emphasis laid upon building houses to let.

Was it complacency or enthusiastic optimism that prompted the statement that “the local authorities must be looked to as the organisations and source for the building of the main bulk of the housing programme, because they were admirably suited for that purpose”? And why the attack upon building societies in the statement that many of these were now nothing but money lending societies voraciously supporting speculative builders to house “the higher income groups”? Why, also, the disparaging reference to “building contractors who wanted to hold the public up to racketeer prices”?

It is a little unfortunate that the statesmanship of this first Ministerial pronouncement upon a subject so important to the building industry should have been muddied by doctrinaire animadversions excusable only during an election campaign. It would be more unfortunate if the housing of the nation, the savings of the small investor as managed by the building societies and the organisation and potential of the building industry were to become the shuttlecocks of politics.

Before it is too late, we should like to urge the Government - even at the risk of some loss of face - to review its policy of sole reliance upon local authorities. This will probably lead to disappointment. Costs will soar and the houses will not be built in the needed numbers. Local authorities are notoriously slow. Armed with powers to grant or refuse building licences to private enterprise, they are already issuing licences only in such small numbers as make economic building impossible.

No doubt they fear that to the extent that labour is employed by private enterprise it will not be available for their own schemes. They are encouraged in this view by Mr. Bevan’s threat to suspend the power to issue these licences if local authori- ties should exercise this power too generously. Meantime labour is returning to the industry from the armed forces and from munitions at a much quicker pace than it can be absorbed upon local authority housing, and there is considerable danger of unemployment in the building industry.

We also view with more than a little misgiving the proposal for the central purchase of building materials and components. We recall the fiasco of the D.B.M.S., a Government Department established after the last war to carry into effect a similar proposal. Under its administration roofing tiles arrived on a building site before the damp-proof coursing, cast-iron soil pipes were delivered instead of fireclay drain pipes.

Production in some factories had to be closed down for lack of storage space, while other factories continued to receive delivery instructions for goods that there would be no chance of manufacturing for months ahead. Trucks of bricks passed each other to and from remote destinations.

Frantic contractors, whose work was held up for lack of essential materials, were grudgingly and belatedly permitted to purchase these in the open markets, but in minute and consequently uneconomic quantities. Ultimately the Department was wound up at untold loss to the National Exchequer. What guarantee is there that the same process will not be repeated?

While our concern is practical, not political, we must nevertheless call attention to some unjustifiable confusion between the lower income groups and the renting householder. Is there to be a means test applied to those who would occupy council houses or are we to see a repetition of 1920-1924, when all and sundry (provided they had the ear of a town councillor) could occupy these houses? If there is to be a means test, is the skilled craftsman or executive to remain homeless while the labourer and clerk get a council house? And what about the returning soldier who wants to own the home he lives in?

Mr. Bevan says that so long as he remains Minister of Health he does not propose to “encourage people to acquire mortgages that would be gravestones round their necks.” It is not thus that the average home-owner regards his mortgage payments. Rather it is as a more profitable equivalent to rents paid to the owner - whether the owner be a private person or a local authority.

Concentration upon building houses to let is economically unsound. The Government, said Mr. Bevan, would welcome other agencies prepared to build for letting, but in answer to an interjected question as to whether houses so provided would earn the same grants the Minister was extremely cautious and committed himself only to the extent of saying that each scheme would be considered on its merits. Some more definite assurance is required both as regards houses which the industry may provide for letting and as regards subsidies for the man who is prepared to house himself. Discrimination in favour of any class of the community is unjustified.

The crux of the solution of the housing problem is the reduction of building costs, and this fact is fully appreciated by the Minister of Health. The Minister, however, does not appear to have any suggestion for securing the required reduction other than to resist high tenders. This is a policy of negation and, as Mr. Hudson pointed out, “merely to reject tenders which are too high may produce not houses but unemployment.”

Leader, 9 August 1946

THE NEW TOWNS

THE final report of Lord Reith’s New Towns Committee opens with a reference to the First and Second interim reports to the Ministry of Town and Country Planning. The first, presented on January 21, was concerned primarily with the form of agency and the legislation required, while the second of April 9 was made urgent by the unexpected opportunity to introduce the New Towns Bill, and dealt with factors that had to be considered in advance of the legislative provisions. The sequence of presentation, it is explained, is not therefore that which would have been adopted had it been possible to submit a single and complete report on the subject, and there are consequently points on which the present report refers to the two previous ones.

It is hoped that this Report will provide ideas and guidance for those who will have the responsibility for creating new towns. Though this raises many unique issues, it depends largely on techniques applicable to other forms of development and familiar to specialists in this field of activity; therefore its value is perhaps greater in the general interest it affords to the public at large, which in one way or another will be directly concerned with the enterprises contemplated.

The subject is treated in a manner that makes it readable to the layman, and its reasoned arguments can be easily appreciated without undue demands on technical knowledge. A broad view is taken of the varieties of attitude which investigation has disclosed and particular care has been taken not to allow the recommendations to be influenced by cut-and-dried dogmas as to methods of planning or by defining too meticulously any specific types of procedure. The picture is put in an attractive form, while at the same time it covers the whole range of activities involved.

The report opens with a consideration of the relative merits of extending an existing town or village as against starting on a comparatively free site. In the one case it is agreed that many small towns would greatly benefit by being extended, but there would be more difficulty in dealing with existing property interests, and there would be many disturbances to local interests giving rise to a genuine conflicts and hardships not capable of being altogether eliminated. On the other hand, a new town simplifies the administrative structure and tends to offer more freedom in the selection of a suitable area, which, as a rule, is held to outweigh the initial difficulties in providing a completely new organisation for transport and services. The decision is that in most cases the selection of an unoccupied site is the more practicable proposition.

The next consideration is the appropriate size for such towns, which is regarded as ranging for provision for a population of from 20,000 to 60,000; the question of the areas required to afford appropriate living conditions for these numbers receives careful analysis, and this brings up perhaps the only important point on which the report can be seriously challenged. This analysis, though detailed, is undoubtedly somewhat sketchy, resulting in a serious overstatement as to the areas required. Thus a town of 40,000 is given a diameter, for the building area, of over 2 miles and one of 60,000 nearly 3 miles; in the latter case this is a far greater area than is occupied, for example, by Coventry, Plymouth, or Southampton, towns of about three times this population.

Of course, the obvious reply would be that these cities are not laid out on ideal lines, but the discrepancy is so marked that this argument is not conclusive, and a closer examination shows that the areas given are some 25 per cent. more than required for planning in accordance with the very highest standards at present demanded if these were taken as a basis for skilful town planning, and this without including in the “Peripheral Belt” any part of the open space, a perfectly legitimate procedure.

We have emphasised this point, as it is not only uneconomic to extend a town area beyond what is requisite, but is also detrimental to the convenience of the inhabitants, involving longer distances to be traversed for workers and those attending to various duties within the built-up area. This criticism does not extend to the recommendations for the belt of open space around the town, which is most valuable in providing for fresh food and preventing sporadic expansion; in fact, as is indicated, it is best for land even further out to be regarded as agricultural in order to conform to a balanced economy in supplies.

Everyone will appreciate the attention directed to good design and the measures of control to be taken to secure this, which it is considered should aim at a judicious blend of firmness and flexibility; various alternative methods are reviewed for dealing with this and with the revision of bye-laws for buildings and streets, which often contain redundancies and anachronisms. Building regulations should be so drafted as to permit the use of modern standards and new ideas while safeguarding such public interests as health, convenience, light and air, good construction and minimising fire risks; application must not, however, be too rigid. Better standards for the equipment of homes should be maintained, and the advantages of district heating are mentioned, though the final decision as to the degree to which this can advantageously be employed still awaits the report of the sub-committee of the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research, to which this question has been referred.

It is recognised that advertising in some form is a necessity and it is proposed that this may be met by the selection of suitable positions for a number of well-designed poster boards, which should be controlled so as to interfere as little as possible with the general amenities. In conclusion, it must be pointed out that the report covers practically every aspect of town life and reviews most comprehensively the type of provision calculated to give the best results, while making allowance for the occupational, climatic and other variations likely to occur.

More from the archives:

>> Nelson’s Column runs out of money, 1843-44

>> The clearance of London’s worst slum, 1843-46

>> The construction of the Palace of Westminster, 1847

>> Benjamin Disraeli’s proposal to hang architects, 1847

>> The Crystal Palace’s leaking roof, 1851

>> Cleaning up the Great Stink, 1858

>> Setbacks on the world’s first underground railway, 1860

>> The opening of Clifton Suspension Bridge, 1864

>> Replacing Old Smithfield Market, 1864-68

>> Alternative designs for Manchester Town Hall, 1868

>> The construction of the Forth Bridge, 1873-90

>> The demolition of Northumberland House, 1874

>> Dodging falling bricks at the Natural History Museum construction site, 1876

>> An alternative proposal for Tower Bridge, 1878

>> The Tay Bridge disaster, 1879

>> Building in Bombay, 1879 - 1892

>> Cologne Cathedral’s topping out ceremony, 1880

>> Britain’s dim view of the Eiffel Tower, 1886-89

>> First proposals for the Glasgow Subway, 1887

>> The construction of Westminster Cathedral, 1895-1902

>> Westminster’s unbuilt gothic skyscraper 1904

>> The great San Francisco earthquake, 1906

>> The construction of New York’s Woolworth Building, 1911-13

>> The First World War breaks out, 1914

>> The Great War drags on, 1915-16

>> London’s first air raids, 1918

>> The Chrysler Building and the Empire State Building, 1930

>> The Daily Express Building, 1932

>> Outbreak of the Second World War, 1939

>> Britain celebrates victory in Europe, 1945

>> How buildings were affected by the atomic bombs dropped on Japan, 1946

No comments yet