Carillion’s collapse has left 30,000 subcontractors out of pocket to the tune of £1.2bn. Their misfortune is largely the result of supply chain payment practices that MPs have called ‘outrageous’. How was the contractor allowed to get away with this, and what can be done to stop it happening again?

Kevin McLoughlin, managing director of £8m-turnover K&M McLoughlin Decorating, is just one of the people hit by the collapse last week of the £5bn-turnover construction and services giant Carillion. His business is owed £230,000, primarily for work done finishing the first phase of housing at the Battersea Power Station development, and Carillion’s demise means he’s also had to write off half a million pounds’ pipeline of work for it. He has already laid off 10 temporary workers from his 200-strong business.

While McLoughlin says his company, which has worked on Olympic venues and the new Google headquarters, is well able to withstand these blows, Tim Hopkinson, president of the Building & Engineering Services Association (BESA), is in no doubt of the severity of its impact. “The real outfall will take several months to be felt. The supply chain has to be supported or else a real catastrophe could unwind, which is the last thing the industry needs,” he says.

“We’re big enough to sustain the loss. I feel for those companies who aren’t. For us it’s a black eye, but others are ending up in the morgue”

Director of a specialisst contractor

With at least £1.2bn estimated as owed by Carillion to up to 30,000 suppliers at the time of its liquidation, the impact of its collapse will be felt far and wide. But specialist contractors and subcontractors are also asking serious questions about its conduct with its supply chain prior to its insolvency, and whether a company behaving in such a way should ever be endorsed with public work. The collapse also raises even broader questions about how to reform the way work is procured, let and won to avoid anything like Carillion’s fall ever happening again.

Catastrophe

Suzannah Nichol, chief executive of industry body Build UK, which counts contractors, clients and subcontractors among its members, says there is no doubt the supply chain is being “battered” by the fall of Carillion, with staff already being laid off where there are no replacement jobs for them to go. “We’ve got one member £4m out of pocket, but they’re robust enough that it won’t finish them off. But we’ve got another, a small contractor, who is owed £87,000, which is 10% of their turnover – and it really might drive them under. It’s a domino effect, meaning even those that chose not to work with Carillion can be hit if someone they work for did,” she says.

One director of a specialist contractor, working on the delayed £350m Midland Metropolitan Hospital job for Carillion, who declined to be named because of ongoing negotiations with the client to finish the job, said he was also owed hundreds of thousands of pounds and had laid off site labour. “We’re big enough to sustain it,” he said, “but I feel for those companies who aren’t. For us it’s a black eye, but others are ending up in the morgue.”

UK banks, following requests from government and trade bodies including Build UK, have said they will support Carillion suppliers with emergency measures such as overdraft extensions and payment holidays. Lloyds Bank, for example, has announced the setting-up of a £50m emergency fund for this purpose. Despite this, Carillion subbies are already finding out they cannot necessarily rely on the generosity of their lenders, thereby compounding the situation they face. David Frise, chief executive of the trade body Finishes & Interiors Sector (FIS), said: “We had one member in our office, they got a call from their bank manager at 10am Monday morning after the liquidation was announced. He wasn’t just calling to say hello. It was: ‘How exposed are you?’ It sums up the attitude.”

In particular, it appears banks involved in Carillion’s supply chain financing scheme are not processing payments to suppliers even when they were certified approved by Carillion prior to its collapse. K&M Decorating’s McLoughlin says his £230,000 invoice was signed off and approved by Carillion prior to its fall into liquidation, but that the bank that financed the prompt payment of his bill, Lloyds, was refusing to pay the invoice. While McLoughlin says his business is well able to withstand the blows, he feels let down. “We thought this finance scheme was a good way of getting money, it was safe, it was ring-fenced – at least that’s what we thought. But the bank says they’re not accepting the invoice.”

Lloyds Bank declined to comment on the specifics of McLoughlin’s situation. However, it is understood that Carillion’s supply chain finance scheme was set up in a way that meant the bank was not legally liable to pay suppliers if Carillion went under, and that Lloyds, accordingly, will not pay suppliers, because it has no way of reclaiming the money itself with Carillion in liquidation.

Rudi Klein, chief executive of trade body the Specialist Engineering Contractors’ Group (SEC Group), says: “We’ve heard this quite a bit from our members. People thought they were protected because they signed an agreement with the bank, but with one or two exceptions, the banks are saying no.”

No surprise

For many, however, the state suppliers have been left in is to be expected from a business that operated in the way Carillion did. Klein says he received more complaints about alleged malpractice and mistreatment of suppliers by Carillion over recent years than about any other main contractor. “People are seriously angry and now everything’s coming out of the woodwork. I’m getting emails from people saying ‘the bully’s gone’. That’s how they were regarded.” Nichol of Build UK, which until last week counted Carillion as a member, agrees that while “many companies have reputations for poor payment,” this applied to “Carillion particularly”.

Klein says he has heard numerous reports of firms having retentions withheld, and of “rebates” to Carillion being demanded for work already done. He cites an example of one complaint brought to him several years ago by an SEC Group member over the £100m Paddington Integrated Project on Crossrail. Here Crossrail had stipulated that Carillion set up a project bank account, designed to hold suppliers’ money in a ring-fenced account to guarantee prompt payment. However, Klein alleges that when the SEC Group member complained of not being able to access a £1m debt, it was discovered that Carillion had simply set up its own bank account with the name “Project Bank Account”, but which was not independent of the contractors and did not allow suppliers to access their money. “Carillion in the end was forced to set one up,” says Klein, “but in response they said they would not bid for any more Crossrail work.”

“They lost their focus and the professionalism of the construction business went down - proven by the contracts they were signing”

Former senior executive at Carillion

A Crossrail spokesperson said: “Project Bank Accounts have been successfully used on all Crossrail tier 1 contracts. Crossrail set up each of the accounts for the payment of contractors and sub-contractors on Crossrail.”

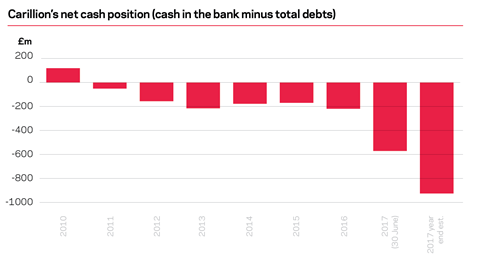

If Carillion’s behaviour implied it was focused on keeping cash in its business then this was, from 2011 onwards, understandable. That was the year its net cash (cash in the bank minus its total debts) fell into negative territory – meaning it had no way to pay all its debts if they came due. By 2013, this “net borrowing” had broken the £200m mark, and at the time of the company’s last published interim accounts from June last year was nearly £600m (see graph).

The most notorious element of this cash management was Carillion’s decision, in 2013, to impose 120-day payment terms as standard on its suppliers – despite the government saying all firms working on public contracts should pay within 30 days. Carillion justified this by at the same time setting up the supply chain finance scheme under which suppliers could access their pay much more quickly – but for a fee. It is worth noting that many suppliers were content with this arrangement, even if it meant sacrificing some of their profit to get paid in a reasonable timeframe. K&M’s McLoughlin said that under the supply chain finance scheme, Carillion always paid “on the nose” and was a “great company” to work for. The Midland Metropolitan Hospital contractor, similarly, said Carillion “paid on time and treated us fairly”.

However, others were appalled that Carillion demanded suppliers sacrifice some of their earnings simply to get paid in the timeframe set as acceptable by the government. Conservative and Labour MPs lined up to criticise the firm, deeming its policy “outrageous” and “appalling”. But the benefit to Carillion was clear: with a turnover of £4bn at the time, each additional month it could hold on to its subbies’ money improved its cash position by around £350m. Conversely, paying more quickly would have sucked cash out at a similar rate. Klein says: “Setting up supply chain finance was effectively an admission it couldn’t afford to pay its supply chain.”

Taking action

Nichol at Build UK says the fall of Carillion should now be seen as an opportunity to change the industry to ensure a similar collapse in the future is avoided. This means moving away from a culture of “lowest cost”, where fixed-price contractors take on huge risks at wafer-thin margins in order to keep cash coming in. “This is about how we value construction. Some companies feel caught between the need to take on work and the fear of losing every contract if they price it properly because someone else will undercut them.

“The industry knows that what it’s doing isn’t working; it recognises that. Our job is to work out: what does different look like?” she says.

One key change she pinpoints is around payment times, where the government’s own rules designed to ensure 30-day payment to suppliers, introduced in February 2015, have been ignored. She says: “If on every new government project it is clearly indicated that these are the rules, the requirements for government work, then everyone knows the rules of play. Carillion publicly had 120-payment terms, yet that never seemed to be questioned by government. It needs to be very clear what happens if 30-day payment isn’t met.”

SEC Group’s Klein wants 30-day payment policed by a “yellow card” and “red card” system, where contractors in breach are first warned and ultimately excluded from government work for two years if they don’t reform.

And while Nichol isn’t yet ready to detail what other specific policies need to change, Klein has no such reticence. He wants use of project bank accounts (PBA) to be mandated across government, saying the common use of PBAs by the Highways Agency is already looking likely to mean Carillion suppliers on those contracts have largely been protected from its collapse. He also wants the government to support the Aldous bill, currently before parliament, which aims to ensure the ring-fencing of retentions in a similar fashion as PBAs protect payments overall.

Klein says his conversations with business secretary Greg Clark indicate he is considering both matters. “I told Greg Clark that if project bank accounts had been in place across the public sector before Carillion’s collapse, the losses would be significantly less. He said he couldn’t disagree, and that retentions is something the government had to take into consideration. He knows we have to have a rethink.”

BESA’s Hopkinson has a similar diagnosis, but says short-term support for suppliers is needed in addition, to stop the disaster of Carillion turning into a catastrophe for the industry.

Others fear that despite Carillion’s downfall, the industry and its clients will carry on regardless. One consultant, who didn’t want to be named, said that while cost consultancies often advise clients against accepting lowest bids, if the client insists then consultants will go along with it. He said: “I don’t think things will change, but they should. We all share some responsibility for what happened.”

The FIS’ Frise adds: “Nobody comes away from this with clean hands. It’s like with the Grenfell tragedy – you can’t say straight away exactly what the specific cause was, but you can immediately recognise the culture that produced it.”

There are optimists in the industry who feel that Carillion’s collapse can be a turning point for the sector. K&M’s McLoughlin for one says: “In the long term this could be very, very positive.

I really think the government will have to look again at procurement. The clients are really pissed off and want to ensure it doesn’t happen again. This model of winning work has to change.” Many firms will hope that this is the moment when, finally, these calls are heeded.

No comments yet