With regional government debt spiralling into trillions of pounds, there are growing fears that China’s rise might not be quite so irresistible after all

When Wen Jiabao stood up to deliver his final address as Chinese premier in March this year, he was able to reflect on some remarkable achievements in the ongoing development of his country. China has seen average annual growth of 9.9% over the last 35 years, and in the past five years alone some 30 million homes have been either renovated or constructed, over 12,000 miles of railway delivered and 378,000 miles of roads built.

However, as Wen passes the premiership to Li Keqiang, there are signs that China’s development is beginning to slow, with growth in 2012 of 7.8%. And it’s looking likely that last year wasn’t a blip: the economy was 7.7% larger in the first quarter of this year compared to the same period in 2012, the slowest pace of expansion since the Asian financial crisis at the end of the last century. The Chinese government has recognised the shift and revised its ambitions accordingly, with the growth target set at 7.5% for 2013 and every year until 2020.

There are also doubts about whether even this adjusted level of growth can be sustained. Professor Michael Pettis of Beijing Business School warned last year that growth will fall to around 3% this decade. Pettis argues that massive state investment can drive growth but that eventually it becomes difficult to identify economically viable projects. And once investment starts to be misallocated, debts rise more quickly than the economy’s ability to service them. Pettis claims that China has been over-investing for at least the past five years.

I went to do some business development work in western China and that bore out my feeling that there is a bit of a wave moving from east to west

Then there is the question of debt. It may sound odd given that China notoriously owns around $1.2 trillion of US debt, but the country does have borrowing issues of its own. In April this year, credit rating agency Fitch cut China’s sovereign credit rating - the first time that any of the international agencies have done so since 1999. The following week Moody’s cut its outlook in China from “positive” to “stable”. Then Zhang Ke, the head of major Chinese accounting firm ShineWing, told the Financial Times that local government debt is “out of control” and could ultimately cause a global shock “even bigger than the US housing crisis”.

But what impact have the change of leadership, the economic slowdown and the mounting local authority debt had on the construction industry? And what impact is that likely to have on UK firms already established or looking to grow their business in China?

A little local difficulty

In the short term, the change of leadership did lead to some hesitation over embarking on major projects. In China, when there is a change of leadership at a national level, the same thing happens in local government and state-owned enterprises (SOEs). As one iron ore executive, whose company’s fortunes are inextricably tied to development levels in China, puts it: “As most building and infrastructure projects are controlled by local government or by SOEs, there would be no approvals, no action and no work while the leadership changed over.”

This inevitably has had an impact on UK firms working in the country, particularly architects waiting for the results of design competitions. “Leading up to the change we had a lot of pent-up demand,” says David Cash, chairman of architect BDP, which has been operating in China for around two years. “There were a lot of potential projects but not much happening. Then there was a flurry of activity afterwards. There are also some new local leaders coming into place - new mayors coming in wanting to make their mark with a new office development or cultural centre.”

Samson Sin, managing director for China and Hong Kong at multidisciplinary consultancy Atkins, agrees. Atkins has been operating in China since 1994 and Sin has seen several changes of leadership in that time. “It always happens when there is a change of leadership,” he says. “Like our competitors, we experienced a slowdown in the second quarter of last year and up until the final quarter, but things are moving again.”

I went to do some business development work in western China and that bore out my feeling that there is a bit of a wave moving from east to west

David Cash, BDP

The local government debt is, however, more problematic. Major, nationally significant infrastructure projects are undertaken by central government - formerly by the Ministry of Railways, now subsumed into a super-ministry - but the vast majority of construction in China is led by local government, meaning that UK construction firms are likely to be engaged by public bodies at the provincial or prefectural level.

While state investment has driven China’s economic growth for more than three decades and has been fairly consistent, the country was not immune to the global financial crisis. So, when the crisis hit in 2008, the central government developed a stimulus package aimed at helping China to ride out the storm. This largely amounted to an instruction to China’s banks to make loans to local government to support development projects. Local government was encouraged to take out the loans, which it did with some abandon: the various layers of local government in China are now estimated to owe between RMB10 trillion and RMB20 trillion (£1.05 trillion and £2.1 trillion).

According to Steve Tsang, the director of the China Policy Institute, a think tank with bases in the UK, China and Malaysia, the level of debt has started to seriously worry central government, which in turn has led to a contraction in local government-led development. “Some of those loans are starting to mature,” he says. “Local government isn’t all that worried - they always have Big Brother - but central government is worried. They’re not pumping in any more money. It’s mostly that local government isn’t investing in as many [new] projects, but [in addition] some previously discussed projects haven’t gone ahead.”

Tsang says that local government in China has form when it comes to bad debt, with a similar situation arising 15 years ago, although on a much smaller scale. In that instance, he says, central government managed to sweep the problem under the carpet. “Can they do it again? Who knows, but it is a major issue,” says Tsang. “There’s a lack of transparency in the banking system, so a lot can happen behind the scenes and there’s no evidence that the government isn’t managing the situation, but it could just be storing up problems.”

According to one China observer, who preferred to remain anonymous: “The whole issue is extremely opaque. Nobody really knows the extent of local government debt, but a lot of money has gone into infrastructure and real estate projects, many of which now lie empty. With non-performing assets, much of these loans must become bad debt eventually when the authorities can no longer roll it over.”

Go west

The problems emerging in local government as a result of China’s response to the global financial crisis tend to support Michael Pettis’ theory that the country has been over-investing in projects that aren’t providing sufficient return. However, many analysts argue that there remain major investment opportunities in China that could sensibly support economic development and produce a sensible return.

Generally speaking, the eastern seaboard in China is increasingly developed, but the further west one travels the greater the need for investment and development. “I went to do some business development work in western China and that bore out my feeling that there is a bit of a wave moving from east to west,” says BDP’s Cash. “There is a lot of stimulus for development in less developed western China.”

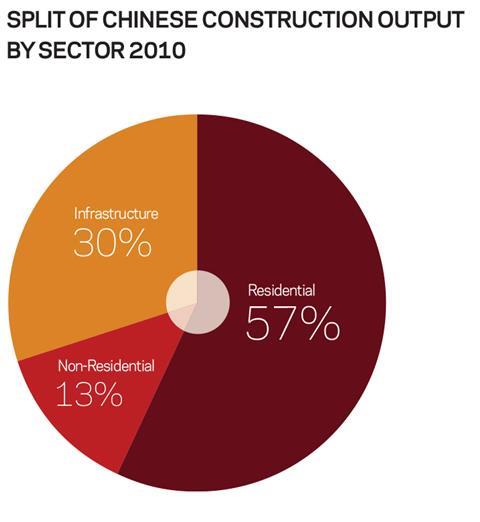

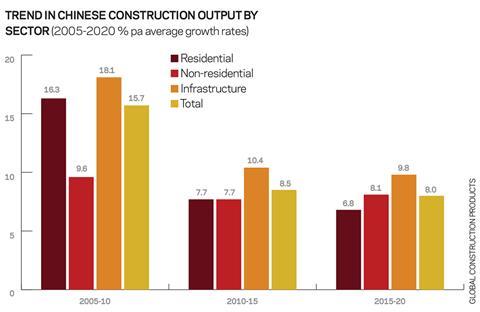

What’s more, while the debt issues in China’s local government are clearly serious and need watching, it should be remembered that the anticipated annual economic growth over the next seven years of 7.5% is still the envy of all western nations bar none. Forecast’s Global Construction Perspectives and Oxfor Economics are due to release a report next month, but their 2012 report anticipates average growth in construction output of 8.5% over the next three years. As a result, many UK firms continue to have high hopes for their Chinese operations. Architecture firm Make, for instance, recently added two new members of staff to its Beijing office and founder Ken Shuttleworth talks enthusiastically about the “hunger for British know-how” in China.

Exactly what know-how is needed, however, is changing. Local government debt is combining with a change in mood music at the top to drive China’s city leaders towards more economically and environmentally sustainable growth. For instance, Atkins’ Sin says he is seeing a far greater concentration on re-using urban land rather than simply moving on to the next greenfield site, quoting the company’s masterplan for Nanjing waterfront as an example. “We do have lots of enquiries from cities about how to make development more sustainable. They’re looking at enhancing value, which is a good move for companies like us.”

So construction in China is changing. The growth-at-any-cost approach seen in recent decades is being replaced with lower growth targets from central government combined with a more sustainable approach to development. That actually provides opportunities for western firms. “In the first 10 years we were in China they really needed international companies, but now they can do a lot themselves,” says Sin. “They can design and build some really big things on greenfield sites, but not on brownfield sites. They still require those skills from international companies. The lessons learned elsewhere are important to them.”

A diplomatic crisis?

Much was made earlier this month of the apparent ticking off prime minister David Cameron received from the Chinese government over his meeting in London in May last year with the Dalai Lama. The Tibetan spiritual leader is seeking greater autonomy for his homeland, something that the Chinese government is firmly set against.

The media storm around the issue was prompted by a story published on the Chinese government’s official website, which included a statement from foreign ministry spokeswoman Hua Chunying. She said: “China hopes the British side will earnestly respect its concern on the Tibet-related issues and take concrete actions to create favourable conditions for bilateral relations to grow.”

The statement led to speculation in the British press that China could cut investment into the UK, potentially scuppering major transport initiatives and other large-scale developments. In response, No 10 said that Cameron would be visiting Beijing by the end of the year, that 14 meetings between UK ministers and their Chinese counterparts had taken place since May last year and that Chinese investment into the UK totalled $8bn (£5.3bn) in

The UK government’s assertion that the dispute over the Dalai Lama meeting hasn’t had an impact on Chinese investment into the UK - or on British firms’ chances of doing business in China - is backed by the China Policy Institute, a think tank with bases in the UK, China and Malaysia. “I don’t buy it at all,” says the institute’s director Steve Tsang. “The idea that if the Chinese were to be successful in bidding for HS2, they would then withdraw because Cameron has been talking to the Dalai Lama is absurd.”

No comments yet