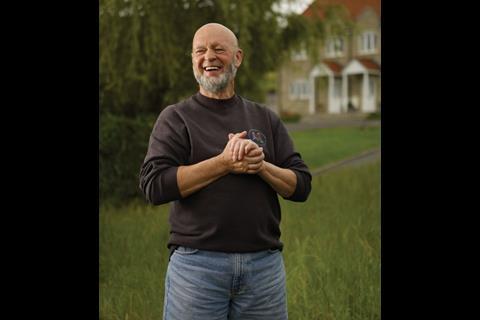

You might think that a man with 900 acres of farmland and the Glastonbury festival to run has enough to keep himself busy. But Michael Eavis has decided to help solve the rural housing crisis as well. Thom Gibbs finds out why

The walls of Michael Eavis’ living room are plastered with framed gold discs. CDs are piled everywhere and there’s a shelf full of NME awards – five for “Best Festival” and the “Godlike Genius” award that Eavis won in 1995. A portrait of John Peel hangs below them. Outside, in the grounds around his Somerset farmhouse, a few dozen cows mooch around and the frame of Glastonbury’s famous Pyramid stage is just visible in the distance.

Eavis rose to fame as the father of UK festivals and since 1969 he has hosted concerts on part of his grounds and farmed the rest of it – he still sees himself as first and foremost a farmer. Recently, however, he has come up with a third, entirely new, use for his land: to build affordable homes on. Eighteen have already been built about a mile from his own house, on a site formerly used for grazing, and another four are planned by the end of the year. The houses are owned by Hastoe Housing Association, although Eavis drew up a covenant to ensure they were rented to people from the Pilton area.

So what inspired Eavis, a man with a sprawling farmhouse, 900 acres of farmland and 400 Friesian dairy cattle, to give up a chunk of his own property free, gratis and for nothing? “House prices here are going through the roof,” he says. “They are approaching £400,000 when lots of people around here earn £20,000 a year.”

To help ease the situation Eavis decided to build affordable homes, donating the land and the stone used in the construction. He also put up some of his own money for features such as fireplaces and chimneys, as he wanted the homes to be attractive and fit in with the feel of Pilton.

He hopes to see similar schemes up and down the country. “We would like to be an example to other villages,” he says. “It’s easy if you’ve got the land – you just apply for a [government] grant and get on with it.”

This can-do attitude led him this year to invite a coalition of interested organisations to investigate festival-goers’ understanding of affordable housing. More than 1,000 people attending Glastonbury this year took part in the survey. And last month Eavis spoke at a seminar aimed at tackling barriers to affordable housing. “I wanted to start an awareness campaign to highlight the need for many more affordable homes. All over the country youngsters have to leave where they grew up because they can’t afford to live there when they set up their own home.”

It is a message echoed last month by Liberal Democrat MP Matthew Taylor, who called for an overhaul of housing and planning policy to enable young people to live in rural areas.

Eavis’ venture into housebuilding stemmed from his strong connections with and loyalty to the area, particularly his own village of Pilton, where the festival is held. He hated seeing local houses being snapped up by outsiders retiring to the countryside. “That was the real crisis for me,” he says. “I felt they were taking houses away from the kind of people who belong here, with family values, who were valuable to the village.”

He has enjoyed strong support. The Glastonbury survey revealed that 82% of people would be pleased to see affordable housing close to where they live. Outside Glastonbury, however, there is plenty of opposition. “Generally, there is reluctance in England about having too many council or affordable houses, and renting is rather frowned upon. People need to change their attitudes, because renting is a really good way to go for lots of people,” says Eavis. “We have had some opposition at council level, but despite the negative stereotypes about people who live in affordable housing, we’ve generally been supported by them so far.”

Ultimately, the driving force behind Eavis’ housing project is to preserve the spirit of the village he grew up in. Eavis, whose family has lived on Worthy Farm for 150 years, speaks proudly about the community and the sports pavilion he built for it in 2007, and he waxes lyrical about nights spent in the working men’s club playing skittles. It’s no surprise that the homes have been built in stone to fit in with the local character, and they have clay tiles and traditional wood-burning stoves.

Driving the mile or so back to the farm from the site of the new houses in Pilton, Eavis pulls over three times to speak to some workers investigating a drain, a woman undertaking a geological survey and, finally, a team of builders working on a feed barn. He quizzes each of them about what they’re up to and says goodbye with a cheery “well done”. It’s a perfect, if somewhat comical, exhibition of British village life.

And the idea of preserving this way of life is what motivates Eavis to use his money and influence. “Housing is a campaigning issue,” he says. “It’s great to draw attention to issues like the war in Iraq and animal conservation but they are not on our doorstep. To do something about a local issue that has a real impact on people’s lives here is refreshing.”

Eavis on Glastinbury

Rain

We’ve got to the point where we can virtually do no wrong with the festival, so it’s just the rain that can bugger us up. It plays on my mind leading up to it every year, and always worries me because good weather makes such a difference.

Money

I’ve always borrowed more money than I should and I’ve never really been financially solvent, but I don’t want to make money for myself through the festival. There’s not enough there to cream off anyway. We have 20,000 volunteers and charity workers here every year, and if I started driving around in a Bentley, there would be a few people saying “hang on, what’s happening here?”

Showbiz friends

Chris Martin from Coldplay is probably the best friend I’ve made through the festival but I know Peter Gabriel quite well, too. I don’t make a thing of sucking up to pop stars, though.

Cow-friendly tent pegs

We gave away biodegradable potato tent pegs this year but they weren’t very successful. When the festival started the ground was hard and they weren’t quite strong enough – they’re for softer ground really. We didn’t research that properly, but people got the message about not leaving their metal pegs behind because they’re dangerous to cows.

The Jay-Z controversy

We decided to make a change this year and stay away from a Radiohead-type band as headliner, but when it didn’t sell out on the first day, we thought, “oh my God, Glastonbury’s had it, we’re going to fold”. Then the press said it was all Jay-Z’s fault. But in the end I think we sold out on the back of the Jay-Z thing, so it’s quite extraordinary how it turned around.

Postscript

Original print headline: "Micheal Eavis"

No comments yet