A simple funding policy is incentivising the uptake of Passivhaus for schools in Scotland - it should be applied across the UK

The Passivhaus standard is a tried and tested ‘fabric first’ methodology that slashes energy use from buildings and delivers high standards of comfort and health. Monitoring of thousands of Passivhaus buildings proves that energy use, on average, is extremely close to the amount that the modelling predicts. By contrast, in an average new home heating demand can be 60% more than forecast using SAP modelling. The Passivhaus standard delivers buildings that perform as designed, effectively eliminating the performance gap.

It is that building performance “super power” that is making Scottish local authorities embrace Passivhaus for their newbuild school programmes. This has been massively spurred on by a simple but impactful change to the funding criteria established two years ago for the Scottish Government`s Learning Estate Investment Programme (LEIP).

The Scottish Futures Trust (SFT) has developed an outcomes-based funding approach to support the delivery of the LEIP programme. Projects receiving funding need to meet a very clear delivered energy target of 67kWh/m2/yr for core hour/facilities, a comparable target with a typical new build Passivhaus school. Crucially, funding from the Scottish Government is reduced based on any performance gap post-completion.

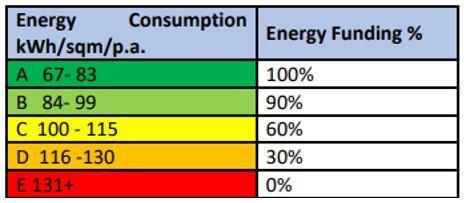

If this energy performance target outcome is not achieved in full, then the funding is reduced

Local authorities pay upfront for the delivery of new school buildings with Scottish Government funding provided through annual payments over 25 years relating to the outcomes, including energy performance, achieved.

Local authorities must provide evidence that the target of 67kWh/m2/yr is achieved. If this energy performance target outcome is not achieved in full, then the Scottish Government energy outcome funding is reduced according to a sliding scale. If the school building exceeds 130kWh/m2/yr for core hour use of energy, no funding for the energy outcome is available.

The funding for the energy outcome starts in year three of the school being in use to allow a two-year period to monitor in-use energy consumption and optimise systems and behaviour. At the end of year two, the in-use energy is measured, and this determines the initial funding band. Following the initial reporting of the energy target at the end of year two, the energy performance and outcome will be assessed every five years (in years seven, 12, 17 and 22).

> Also read: DfE to reshape procurement for crumbling schools estate

Local authorities instigating newbuild school projects in Scotland are now embracing Passivhaus as a way to de-risk funding. While the SFT funding metric doesn’t specifically require building to the Passivhaus standard, as Passivhaus is proven to eliminate the performance gap it effectively guarantees to meet it.

As a result, multiple Scottish Passivhaus school developments are currently under way. These include Currie Community High School, Wester Hailes Education Campus and Maybury Primary School & Health Centre (pictured) for City of Edinburgh Council, Riverside Primary School and Perth High School for Perth & Kinross Council, the Ardrossan Community Campus for North Ayrshire Council, the Dunfermline Learning Campus for Fife Council, and Tain Campus for Highlands Council, to name but a few.

LEIP applies to retrofit projects too. A deep retrofit of St Sophia’s Primary School for East Ayrshire Council aims to meet the same performance metrics by embracing the EnerPHit (Passivhaus retrofit) standard.

While the recently-unveiled DfE Sustainability and Climate Change Strategy has high aspirations, it lacks detail

Could this simple outcomes-based funding policy be applied to the rest of the UK to drive a similar paradigm shift in the performance of buildings as in Scotland? Essentially, yes. There is also no reason why it could not be applied to other types of buildings, including funding criteria for social housing (there is currently a consultation on the proposed Domestic Building Environmental Standards (Scotland) Bill calling for Passivhaus to be mandatory for newbuilds in Scotland).

This is something the Passivhaus Trust has already pressed as part of a Department for Education (DfE) consultation. However, while the recently-unveiled DfE Sustainability and Climate Change Strategy has high aspirations, it lacks detail with no clear focus on performance outcomes. There is no reference to Passivhaus, LETI or RIBA targets. The SFT funding mechanism proves that clear metrics provide a simple way to accelerate best practice and are essential to reward successful delivery.

As well as drastically lowering energy bills, the multiple benefits of Passivhaus – including addressing fuel poverty, healthier buildings, and improved air quality - should be carrot enough to encourage local authorities to embrace the Passivhaus standard. Introducing a financial funding stick such as the one used by the Scottish Futures Trust could give the final push to help the transition of higher building standards, such as Passivhaus, and drive down carbon emissions from the construction sector.

Sarah Lewis is research & policy director at Passivhaus Trust

No comments yet