How they made it

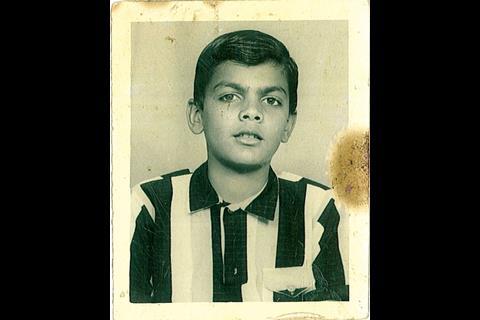

From escaping Uganda to engineering a Stirling prize winner, Hanif Kara’s life has been quite a rollercoaster, but he still puts his success down to being a bit quirky.

What sparked your interest in buildings?

I was about seven years old when it started. My father was a construction site agent in Uganda and, there, children would live on site with their parents. I remember the smell of concrete from an early age. Digging big holes and getting stuff built seemed like fun.

What happened next?

Chaos! At the age of 13 I came to the UK as a refugee. I could barely speak English, so the first two or three years were very traumatic. I flunked all my O-levels, left school at 16 and got a job working in a factory making spray paint. I was quite a bad boy – and a punk rocker, at that stage.

What put you on the straight and narrow?

John Sautell and Frank Mitchell gave me an apprenticeship as a draughtsman at their company, a steel fabricator called Joseph Parks. They sponsored me to do a degree in structural engineering. They also improved me in other ways, like by getting me to wear ties instead of punk T-shirts.

Why didn’t you stick with steelwork?

Two years after I left university, I was still working for Parks but I was bored of fabrication and welding. Besides, I knew there was more money in engineering and at that age, you need a wad. I moved to Allot & Lomax, an engineering consultant in Manchester known for building rollercoasters.

What is working on rollercoasters like?

They’re technically very difficult – all curves and working parts. We’d do safety inspections of small ones and large ones, like the Pepsi Max Big One in Blackpool. It was quite a dirty job because you had to climb up these things when you checked them. Every time someone died on one, you had to check it for safety. It was quite grisly. After one accident I remember picking up fingers.

Why did you move to London?

Allot & Lomax got the job as consultant on Battersea Power Station. John Broome, who owned Alton Towers, wanted to turn it into an amusement park. We spent two years on site, taking out all the insides, the copper and asbestos. It was a dangerous job – I wouldn’t do it again today, but I wanted the money! Unfortunately, Broome went bankrupt and the project was chopped.

When did you begin to make a name for yourself?

When I was working at Anthony Hunt Associates on Richard Rogers’ Lloyds building in the City of London. It was an amazing piece of concrete building and technically very complex.

Why did you set up Adams Kara Taylor?

Big companies identify talented people and pit them against each other. I’ve always thought grouping talent is a much better way of working, so I decided to leave Anthony Hunt. At first I was running dry-cleaning shops. I was making money but it was too boring. So I got together with two colleagues from Anthony Hunt and launched an engineering consultancy.

What were the first few months like?

Hard, hard work. Albert [Taylor] and I left Anthony Hunt on the Friday, and started the firm on the Monday. Robin [Adams] – who at that time was our boss – joined us two months later. We took three people with us – a receptionist, a draughtsman, and one good engineer. Into the mix, I got married around the same time. It was enormously stressful.

When did AKT begin to take off?

In 1999 when we completed Peckham Library. It was a complex design, and we had a highly mischievous architect in Will Alsop who we had to tame but we felt we could do it. Winning the Stirling prize proved we could.

What was the most difficult moment you’ve had at AKT?

I had to ring Zaha Hadid to tell her we couldn’t do something she wanted on the Phaeno Science Centre in Wolfsburg, Germany. In the end, it was fine. She’s a gentle giant. There’s an impression that she beats people up and goes mad, but she can actually be quite shy.

How do you explain the firm’s success?

When we launched there was a gap in the market in offering contractors a design service, because most didn’t have engineers in-house. Also, there was something quirky about this brown guy, this black guy and this white guy setting up a practice together. Peter Rogers always says to me, the thing about you three is you’re weird. People always remember weirdos.

Give us a piece of advice.

You don’t succeed if you sit on your hands. If you’re convinced you’re a genius, then get out there and tell people about it. They don’t have to believe you, but if you have passion, integrity and you’re prepared to work bloody hard, people will want to help you. Remember, the industry wants you to do well, so all you have to do is show them you can do it.

Hanif Kara, 50, co-founder, Adams Kara Taylor

Country of birth

Uganda

1971

Came to the UK as a refugee and went to school in Cheshire

1975

Joined Joseph Parks & Sons as an apprentice draughtsman

1982

Graduated from University of Salford with a degree in structural engineering

1983

Joined Allot & Lomax as graduate engineer

1991

Joined Anthony Hunt Associates

1995

Left Anthony Hunt to set up Adams Kara Taylor

2004

Made honorary fellow of the RIBA and appointed to Cabe review panel

2007

Appointed Cabe commissioner and became part of the mayor’s Design for London review panel

Topics

Specifier 07 March 2008

- 1

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

‘People always remember weirdos ’

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

No comments yet