Architects Jestico + Whiles were tasked with ‘showcasing the science’ of the Cavendish Laboratory to the general public while meeting the exacting requirements of its world-respected scientists. Daniel Gayne visited the lab on a bright autumn day to find out how they rose to the challenge

As we head into the final month of the year, many in the UK will be turning their minds to gift giving. Each of us has a different idea of what makes a good gift – some might hope for a flashy new gadget from the electronics section at John Lewis, others are happy with something as simple as a bar of Toblerone. But, unless you are the University of Cambridge’s physics department, you probably don’t expect your gifts to come in the shape of an £85m cheque.

To be fair, the donation made by the Ray Dolby (of surround-sound fame) estate in 2017, was large even for the famous university. In fact, it was the biggest philanthropic donation ever made to UK science. Dolby’s gift was to be spent on building a new home for the Cavendish Laboratory, where he received his PhD in 1961.

If you find it hard to imagine giving so generously to your own place of education, you might want to bear in mind the lab’s history. Few research organisations can claim a connection to so many Nobel Prize winners that they lose count. The current tally is 31, after staff found a winner down the back of the sofa.

“Someone had got the Nobel Prize back in the 1950s and we figured out he was a Cavendish alumni,” a university staff member tells me. Today, the Cavendish is home to cutting edge research at the forefront of experimental and theoretical physics.

The head of department here said he had seen more people in the first two weeks in this building than he felt he had seen in the past year

Jude Harris, director, Jestico + Whiles

But, despite its illustrious past and highly regarded present, “the Cav” has long been put up in rather inelegant quarters. “This, to us, is Cavendish III,” says Jude Harris, director at the architect of the new building, Jestico + Whiles.

The original lab had been set up in 1874 in Old School Lane in the centre of town, establishing its reputation as an academic heavyweight. That is where JJ Thomson discovered the electron, Ernest Rutherford split the atom and Crick and Watson decoded the structure of DNA.

But, in the 1970s, the lab moved to its second home, a rather inelegant prefabricated building in west Cambridge. Despite its shabbiness, Cavendish II was in many respects a functional building.

“It was quite a low-grade building, but actually really good for the Cavendish because it was very flexible,” Harris explains. “They could just kind of change it around and plug bits of plant onto the side.”

It provided the Cavendish’s 16 research groups with a space which could adapt to the varied and highly specific needs of their respective experiments.

Meeting scientists’ exacting standards

The challenge for the designers of Cavendish III, now known as the Ray Dolby Centre, was to create a facility which replicated and improved on the old Cavendish’s offer to the scientists, but with a more presentable face for a prestigious institution looking to draw in talent from across the world. Delivering the brief began at the front door.

In the old Cavendish, there were 22 separate entrance-exits to the building. “It was a key part of the brief that we bring everyone through a single entrance,” Harris tells me, explaining that the university wanted a building that encouraged “interaction and serendipitous encounters” between colleagues.

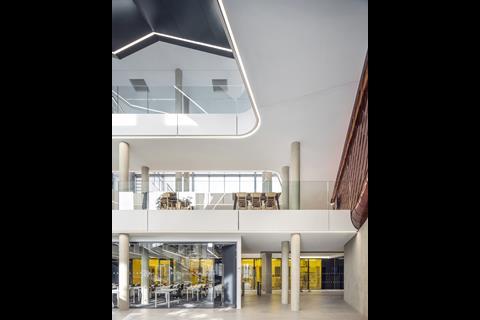

Everyone arriving at the Ray Dolby Centre approaches via a grand staircase and raised piazza, before entering what the architects describe as a “fluid arrival space” dominated by the two lecture theatres, clad in brass fishscales and seeming to defy gravity, floating in the middle of the quadruple-height atrium. Harris says their design for this space seemed to have succeeded in creating the encounters they had been hoping for.

“When the building was opened back in May, the head of department here said he had seen more people in the first two weeks in this building than he felt he had seen in the past year,” he recalls.

Creating connections: the public wing and collaborative spaces

This entrance area is the “public wing”, which occupies roughly a fifth of the whole centre and, as the name suggests, is almost entirely accessible to the public. It is meant to help “showcase the science” to the wider public, with selected exhibits from the Cavendish Collection displaying scientific material and apparatus past and present. The public wing includes 120 and 450-seat lecture theatres, as well as the library and an 80-seat cluster seminar room.

Most of the Dolby building, however, is beyond a “secure line” intended to protect scientists’ research and the safety of the public. This part of the building contains research laboratories, along with workshops, clean rooms, cryostat halls, microscopy suites, offices and collaboration spaces, as well as the services needed to facilitate all this.

It is divided into four principal research wings, separated by three courtyards and each with its own “central utility building” attached at the rear. As is typical in science schemes, offices are on the higher floors and labs lower down, with the most prized space in the basement where conditions can be most easily controlled.

The architects have done their best to reduce replication and the inefficiency created by the old Cavendish’s hodge-podge expansion. While that building was adaptable, it “had its flaws”, with permanent and temporary plants scattered across the building, increasing energy bills and sometimes interfering with work. In the new building, the designers have tried to break down siloes between research groups by creating shared facilities.

“The philosophy of the building is that, yes, there are research groups, but trying to break down the barriers and […] actually sharing and interacting with one another,” says Harris. He explains that where they now have 14 cryostats across two halls, “before they might have been in 14 different laboratories scattered around”.

They have also centralised the permanent services in the aforementioned utility buildings and set aside so-called “grey spaces” outside laboratories for temporary “process” plant. The building has been designed for 30% capacity and there is a corner where an additional wing could be added if needs change in the future.

Ray Dolby Centre in numbers

- 32,900 sq m

- 173 laboratories

- 1,100 members of staff

- 400 seats in the large lecture theatre

- 770 cycle spaces

- £85m donation from the Ray Dolby Foundation

- 2,500 sq m cleanroom facilities

- +/-0.1C close temperature control in laser laboratories

While the active research parts of the building are restricted, the principle of showcasing the science has still been considered. The first thing you come to after passing through the secure line on the ground floor is the “public street”.

“The idea is that the department can bring visiting academics, visiting members of industry, around the building, but actually can see what’s going on,” Harris explains.

Large glass windows look into clean rooms, where scientists use lasers to etch circuits onto silicon wafers – a three-metre plant room hangs in an interstitial floor above, maintaining a laminar flow of air to keep the environment clean.

Historically, says Harris, this kind of work would be done in “big industrial sheds” but in the Dolby Centre they have “kept that visual connection” to these highly-controlled environments and “give people an insight into what’s going on”. The floorplan of the building is “almost like a figure of eight”, with the public street running parallel to a “movement corridor”. The two roads connect in between the clean rooms via “clean” and “dirty” corridors.

This was another way the building is meant to encourage interaction between researchers. “They wanted it to be very circuitous,” says Harris, “they didn’t want any dead-end circulation routes.”

The movement corridor, which backs onto the four central utility buildings, is where the building receives deliveries of equipment and dispatches manufactured goods. Its wide corridors and tough resin floors were intentionally designed for this purpose, which was essential to enabling the move from the old lab in the first place.

While the Dolby building was completed in 2024, it has only been in partial use – largely for teaching – during the past academic year. That’s because it has taken a full year for the research laboratories to make the transition from the old building.

This, Harris explains, was a “huge logistics operation”, in part due to the 98 optical laser tables that had to be moved into the lab. These tables, which are three metres by one metre in size, were part of ongoing experiments and could not be tilted even slightly without disrupting the results. Experiments like these can take a year or more to set up and run, and the scientists were not about to have their hard work squandered by sloppy designers or movers.

Facilitating this logistical move was therefore part of the design brief, with the architects drawing up detailed movement diagrams, tracking the potential movement of laser tables around the building.

Solving the vibration problem

Demonstrating this was one of many things the designers of the building had to do in order to get the scientists on side. “They’re a very demanding group of people,” says Harris. “They have this amazing track record in science to maintain.”

As part of the design process, the architects collected room data sheets for every laboratory, which included things like temperature criteria, humidity criteria, power requirements, and something called “clean earth”. All the partitioning around the cryostat rooms is timber with non-ferrous screws and stainless steel reinforcement in the slab, while a high voltage cable has been “deliberately located” to the west of the site – all to avoid electromagnetic interference.

But perhaps the most important criteria was vibration. “The physicists basically said, ‘we’re not going to take that site unless you can prove to us that it’s as good, if not better, vibration than Cavendish 2’,” says Harris.

For scientists conducting at the tiniest scales, vibration is poison. A great deal of testing was done on the site before construction to demonstrate that it was suitable. Broadly, it seemed to be, apart from a “massive blip” which kept turning up on the graphs. “It turned out it was the double-decker bus going over the speed bump” on JJ Thomson Avenue just in front of the building.

After some adjustments to the road design, they turned their attention to construction solutions to the vibration problem.

Isolating those utility buildings formed part of the solution. Containing fire escapes, plant rooms, elevators, a ground source heat pump and a data centre, they are a hive or disruptive vibrational and electromagnetic interference – what is known in this world as a “bad neighbour”.

As such, they are set to the side of the building and are structurally isolated, with steel-frame construction so they can be “shaking away” independently of the labs.

For the main bulk of the Dolby, structural engineers Ramboll were faced with two options for minimising vibration. “One is what’s called a keel slab solution, which is basically like a boat where you have a keel which kind of stabilizes it,” explains Harris. “That’s quite an expensive solution, because it’s quite difficult to create the profiles of the keel slab and anchor it into the ground.”

The alternative, which the project team ultimately opted for, was simply to put in an incredibly heavy concrete base – in this case a two-metre slab under the basement, which itself is eight metres below grade.

They have left “a pocket out of the slab” in one corner of the building, so that, if they need greater vibration requirements in the future, they can install a keel slab at a later date.

However Harris seems satisfied with achieving VCH vibration criteria, allowing research at the atomic level. “We have some of the best performing vibration space in the country,” he says.

Even after all of this engineering, there was one more vibrational risk. “Some physicists require these very low vibration, quiet environments, but other physicists like blowing things up,” laughs Harris. The solution to this problem was relatively simple, however – keep them as far away from each other as possible.

I am told in vague terms that there is “lots of quantum physics” and that “some elements” of experiments at the large hadron collider in Switzerland are being built in the clean rooms. Some researchers are working on the materials which go on satellites’ solar panels, while others are developing smart toilets to detect infection in urine.

A brief introduction to a researcher called Niamh demonstrates that it is probably a fool’s errand trying to explain it to me in any more detail than this.

>> Read more: A vision for 150,000 homes but no water to supply them. Does Gove’s Cambridge 2040 plan stand a chance?

“The main thing that I’m working on is the tonic-integrated circuits with defects in diamond,” Niamh says. “So what we have is a set of wave guides with implanted tin vacancy defects, which can make a really nice platform for qubits. It’s nicely packaged into this circuit design such that we could interface it with other devices.

“We cool it down to 10 millikelvin, so that’s what the fridge over there is for. So it gets to really low temperatures, and then all of the sort of control of the qubits is done with the optics on the table over here.”

After saying my thank-yous and goodbyes with a look of blank incomprehension plastered across my face, I leave Niamh’s lab and am told simply that she is working on “quantum networking”.

Whatever is going on in these laboratories, it was important enough for the government’s engineering and physical sciences research council to splash out £75m to go along with Dolby’s gift (the rest of the £300m budget was made up from other donors and the university’s own resources). The Dolby Centre is a national facility, which means that 20% of equipment in the lab is to be shared with other scientists across the UK.

Upstairs and out of the labs, there are a few floors of smart but unremarkable office space, set between courtyards and bright, spacious corridors. On the top floor, back on the public side of the secure line, is a large cafe-dining room with a roof terrace for those willing to brave the biting easterly winds, as well as an amazing view out to King’s College and the university library in the distance.

West Cambridge development plans

It is however the immediate view out onto west Cambridge that will see the most change in the coming years. The university has an approved masterplan for the expansion and development of the site, for which the Ray Dolby Centre is a kind of precursor. Across the road is the West Hub, also designed by Jestico + Whiles, which was been built to service the coming development in an effort to satisfy the council.

“The planner said they were not going to give us permission for the 61 hectares of development unless there’s some kind of amenity space,” says Harris. “It’s not a building type that Cambridge has really done before. A lot of its work is focused on the colleges, whereas this is a non-college, publicly accessible teaching and learning building.”

The hub is a multi-functional building that includes a canteen, bar and restaurant, teaching rooms, office space, library and public working spaces. There is little detail as yet on what future development looks like, but the university’s outline permission includes 370,000sq m of academic floorspace, as well as a nursery, retail and leisure space.

As we turn our backs on this vista and loop our way back to the new Cavendish’s one grand entrance-exit, our university guide gets a notification on her phone. “32!” she says, happily but not altogether surprised.

Professor John Clarke, another Cavendish alumnus, had just been awarded this year’s Nobel Prize in physics. With this impressive new home, it is not hard to imagine that there will soon be a thirty-third prize-winner on their list.

Project team

- Jestico + Whiles | Architect

- NBBJ | Executive Architect

- Bouygues | Contractor

- Ramboll | Structural engineering

- Hoare Lea | M&E

- Currie & Brown | Project management

- Aecom | Quantity surveyor

No comments yet