Five years on from the Grenfell fire and four years after Judith Hackitt’s Building A Safer Future report laid the foundations for the Building Safety Act, the construction industry stands accused of dragging its feet on safety. But is the charge entirely fair? Carl Brown reports

Next month marks the fifth anniversary of the Grenfell Tower disaster and while in many ways it does not seem long ago, in others it seems like an eternity given the sheer amount of stuff that has happened since.

Since the fire that killed 72 people on 14 June 2017, we have had Brexit, a global pandemic, worldwide materials shortages and now the war in Ukraine. Debates about the need to make our buildings safe meanwhile have been dominated by the issue of who pays for the removal of cladding from tower blocks, with leaseholders, developers, and more recently product manufacturers, making their case for fairness in the way costs are apportioned.

However, as many of the findings from the ongoing Grenfell inquiry have shown, the building safety issues in the construction sector have been much bigger than just that of unsafe cladding. Few would disagree that the construction industry is in need of much more radical change.

One person who has been watching the industry’s efforts to change itself over the past four years and quietly seething about the lack of progress is Dame Judith Hackitt, whose seminal Building a Safer Future report in 2018 laid the foundation for much of the Building Safety Act which passed into law last month.

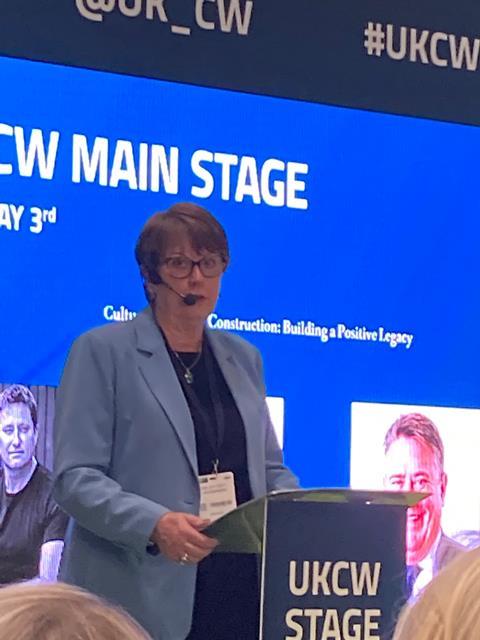

Hackitt told UK Construction Week last week that she has spent four years trying to get the construction industry to improve building safety but has met with “mixed success” as too many have their “head in the sand”.

Hackitt, who advises the government on the act’s passage and implementation, later spoke to Building about her concerns. Visibly frustrated, she rattled off several areas that she thinks the industry should be moving more quickly on. These include being too cautious about insurance concerns, not providing sufficient funding for building safety training, and not engaging enough on moves to establish the “golden thread” of information sharing as required under the act.

“What everyone seems to come up with,” she says, “is ‘I’m waiting for everybody else; I can’t do my bit until they do their bit’.” She says the industry is too often “waiting to be told what to do.” In simple terms, she thinks the industry is “waiting to be told what to do” through legislation and regulation rather than working as hard as it can to develop solutions ahead of the game.

Context

But how fair is all of this? Philip Pamment, head of residential (South) at consultants CPC Project Services, does not downplay the need for change and says Hackitt’s comments are “understandable”, but says the scale of the changes and the current context needs to be recognised when judging the industry’s progress.

Pamment says: “The changes enacted in the Building Safety Act are substantive, strategic and structural. However, they are being driven through at the same time as the construction sector has been dealing with the significant headwinds created by Brexit, covid and now the war in Ukraine.

“These headwinds have disrupted supply chains, driven up costs, increased risks and created a range of unprecedented contractual challenges. The effect of these headwinds has then been magnified by a programme of substantive regulation change to Approved Documents part B, F, L, O, S and Z. This combination is an unprecedented challenge for the sector.”

On top of this, suggests Pamment, there is significant uncertainty about how some of the detail yet to be brought through in secondary legislation will work. These include how the gateway points, which govern building control approval and completion certificate approval, will operate and what happens between now and when this part of the act comes into force in 12 to 18 months’ time.

“Given that developers and clients are currently negotiating contracts that may be subject to these new gateway rules, it is important that the government clarifies the transition arrangements and residual uncertainties as quickly as possible,” says Pamment.

At-a-glance: Building Safety Act

The mammoth 262-page act is intended to “create lasting generational change” to the way residential buildings are constructed and maintained in the UK.

- It will see the creation of a new construction products regulator with the power to remove products from the market, a new building safety regulator and will bring in a requirement for developers to remain members of a New Homes Ombudsman Scheme.

- It aims to provide a series of protections for leaseholders including a retrospective right to sue developers for defective works up to 30 years after a home is completed, along with measures to shield leaseholders from costs for cladding works.

- It gives the government the power to take action against housebuilders not paying to fix fire safety issues.

- There are also measures to ensure there are clearly identified people responsible for safety during the design, build and occupation of a high-rise residential building and a gateway point system to ensure building safety regulatory requirements are met at different stages of the planning and construction process.

He adds that all this “still needs to be finalised before the sector can confidently implement the changes envisaged by Dame Judith more than four years ago”.

But doesn’t this just back up Hackitt’s point that the sector is waiting to be told, rather than leading on safety?

One industry legal expert, who did not wish to be named, says it is understandable if some have been waiting for the act to get Royal Assent in case planks of the legislation changed, and some may already have wasted money by moving too early. She says an example of this was the relatively late decision to remove the requirement for blocks above 7m to have a fire safety manager. “A lot of clients have been appointing building safety managers on the understanding it was going to be one of the core tenets of the regime. These clients did get on with it and now have people with job titles they need to repurpose.”

She says this may not leave firms massively out of pocket because the people moved into other similar roles, but she adds “you can understand the reticence of people to just get on and do things on building safety without an act in place”.

Training

This uncertainty may be behind another of Hackitt’s observations, that not many people have been trained up to improve their competency, despite work being done to set up competency frameworks.

The Competency Steering Group – a pan-industry body of more than 300 organisations or individuals – was set up to look at competency and in October 2020 published its final 164-page report, called Setting the Bar, outlining how a competency regime should look.

Despite this, Hackitt says few people have been put through training alongside the competencies framework and suggested firms do not want to pay to train their staff – “that’s the bit that requires a hand in the pocket to pay for it”.

[The Building Safety Act is] going to mean safer, higher-quality buildings, with designated people to ensure that happens and a building safety regulator as well

Andrew Harrison-Sleap, Howden Group

Hackitt says though that now there is an act on the statute book, this “ought to be the sign” for everyone to get on with training. Draft regulations have been published which will impose a requirement on principal contractors and designers and anyone carrying out any design or building work to be competent for their roles.

Graham Watts, chief executive of the Construction Industry Council (CIC), says he largely agrees with Hackitt that the industry’s efforts on competency have not yet led to the introduction of training to meet the new standards. However, he says: “I’m sure that Judith is partly right but I also think that the industry is ill-prepared for the new legislation and businesses are not sure what they need to do.

“Last minute changes to the legislation, such as the removal of the statutory requirement for a building safety manager have not helped because they have increased the feeling of uncertainty.”

Insurance

Another, area of uncertainty, perhaps the biggest, is insurance. Hackitt says the thing she has heard “more than anything else” from the construction industry is that insurers are “getting in the way and won’t give liability cover” for the necessary changes. Hackitt suggests rather vaguely that construction should crack on with culture change and then the insurers will follow suit as once they see the new culture emerge, confidence will follow.

This reading of the situation, that construction firms are blaming insurance companies for holding back building safety and preventing progress, is strongly disputed by Andrew Harrison-Sleap, executive director and global deputy head of construction at insurance brokers Howden Group. Harrison-Sleap says it is “surprising” if the insurance industry is being blamed, given that the government did not have a regulatory regime in place in the first instance.

He says: “If you look at professional indemnity insurance (PI), insurers are there to indemnify their insureds – for example, a contractor – for the legal liabilities they incur, but the legal liabilities they incur will not only be determined by their practices but also by the legal regime that they sit within. So, to hear that the insurer has a handbrake on this, and they are being brought into question is surprising.”

He says the insurance industry faced an “absolute avalanche” of claims or potential claims following Grenfell and many are still trying to provide PI, although he says there is a difference in size of firm seeking insurance. “The larger contractors with very, very large programmes, large excesses and larger premiums will have a better ability to get coverage for cladding and fire safety claims. Smaller contractors and subcontractors might struggle a bit, but the insurers have generally been pragmatic.”

Rebecca Rees, partner at law firm Trowers & Hamlins, suggests the idea that construction could simply march on without taking into account insurers’ concerns, in the hope that they buy in later on, is not feasible as the “sector won’t move without insurance”.

People need to have insurance, we live in an insurance-based service regime, don’t we? Architects will not do something where they have unlimited liability and they’re not insured

Rebecca Rees, partner at law firm Trowers & Hamlins

The Building Safety Act brings in a duty holder regime which places statutory responsibility for the safety of higher-risk buildings on key individuals at different stages of a building’s life cycle, namely on those who procure, plan, manage and undertake building work. These duty holders will be clients, principle designers, principle contractors and contractors. Rees says these duty holder roles will not be embraced or delivered to their fullest extent if they are not “underpinned by reasonably robust and affordable indemnity insurance”.

She says: “People need to have insurance, we live in an insurance-based service regime, don’t we? Architects [for example] will not do something where they have unlimited liability and they’re not insured. So, you have to be cognisant of what is insurable and what isn’t when you set out that duty holder role, or seek to bring insurers with you in the roles’ design.”

Ultimately, Rees believes that if affordable and effective insurance does not become available, the government “should step in and resolve the market failure”, rather than designing a less effective building safety regime that may well be insurable.

The dutyholder regime is not expected to come into force for another 12 to 18 months, and the regulations setting it out only exist in draft form, which again adds some uncertainty into the mix.

Extending the period of limitation

One late change to the bill that has caused widespread fears about the availability of PI is the government’s decision to extend the time period for compensation claims for retrospective defective building works under the Defective Premises Act from six to 30 years, rather than to 15 years as first announced.

The Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (RICS) has warned that this change could result in insurers “assessing their involvement” in the construction market. It said: “The retrospective extension of the period of limitation will not be viewed positively by insurers, who have been concerned by changes to building regulations, and brings back into scope previously discounted risks which have not been priced into their reserves for claims or into the premiums of the risks that they are currently underwriting.”

See also>> The Building Safety Bill is now law - here’s what you need to know

The CIC has warned that the move could lead to smaller construction firms struggling to get cover and potentially exiting the industry as a result.

Rees also says there are uncertainties about building insurance and how insurers will get comfortable with aspects of the new regime. The act requires buildings to be assessed by the new building safety regulator every five years in order to receive a building assessment certificate. “What happens when you get to that year where your building assessment certificate runs out half way through?” Rees says she is sure the government has thought about this and has a solution, but it would be helpful if this were publicised as soon as possible

However, when it comes to the longer-term picture, Harrison-Sleap has little doubt that the new regime will be welcome by the insurance industry as it should lead to fewer defects in buildings. He says: “It is going to mean safer, higher-quality buildings, with designated people to ensure that happens and a building safety regulator as well.”

But in the short term, the lack of clarity, the fact final regulations are still being worked on, look likely to prolong the hesitancy in the market, and it is difficult for construction firms to progress in some areas as a result. Rees goes as far as to say that she fears “that the implementation of the act in its fullest may be hampered by the lack of availability of appropriate insurance”.

Information sharing

Hackitt also slammed the construction sector for being behind the curve on developing information-sharing through use of technology, compared with other industries. The act requires dutyholders to create and maintain a “golden thread” of information. Rees says Building Information Modelling (BIM), is too often seen as an optional expense to a project and construction therefore remains a traditional sector. She also says the use of BIM and digital solutions are usually seen as the preserve of the offsite and net zero agendas.

One reason construction may be finding it difficult, it has been suggested, is the fragmentary nature of the industry, with its large numbers of different organisations involved. This also creates problems for procurement. Stephen Greenhalgh, the building safety minister, told Building earlier this month that there needs to be a greater focus on quality and then safety will naturally follow. “People have just been thinking about speed and cost,” says Greenhalgh.

However, as Rees and Harrison-Sleap both point out, construction operates a low-margin, highly competitive model, with costs tended to get squeezed down the supply chain. Harrison-Sleap, while saying that construction should be less adversarial in this way, also points out that the government itself procures based on cost. “They want the highest quality at the cheapest cost, don’t they?” he says.

“It’s a fallacy that if you focus more on quality then the price becomes less relevant,” says Rees, who wants to see the government legislate against the “race to the bottom” pricing model for higher-risk buildings “because it is that that sets the agenda”.

See also>> Decay, delay and deregulation: what we have learnt from the Grenfell Inquiry

See also>> Preparing for the Building Safety Bill

Across construction it will be difficult to find anybody who disagrees with the ultimate aim of the Building Safety Act, which is to prevent us ever again having to witness horrific scenes like those of 14 June 2017.

Hackitt is commendably impatient to see the industry cracking on with changing its culture. But it is understandable why change has not been at breakneck pace so far given the challenging trading conditions, insurance concerns, the fragmented operating model and a great deal of uncertainty around how the act’s regulations will work. Hackitt believes that now, with the act on the statute book, the changes will start to feel real and there will be much more attention paid to the huge changes coming down the road.

“There will be an explosion in the number of conferences, not for just the construction industry but for investors, directors at the very top of the pyramid and lawyers will be on their case now saying ‘this is coming get ready for it’,” she says.

“Is that a good thing? Yes, of course it is because it means that everything Stephen [the building safety minister] and I have been saying for the last four years is going to get amplified by other voices.”

One thing is for sure – the industry will have to get its skates on soon when it comes to building safety, otherwise an increasingly agitated Hackitt will be the least of its worries.

No comments yet