Perceptions about post-Brexit Britain, new visa rules and the pandemic have combined to make it more difficult to recruit EU nationals to some construction roles. What is the industry doing about this?

Among the flurry of warnings about the potential negative impacts of Brexit in 2016 – in what was dubbed Project Fear by detractors – were anxious voices from the construction and housebuilding industry. Figures such as David Thomas, chief executive of Barratt, said a vote to leave the EU would mean “even more pressure on skills shortages.”

With estimates at the time that in some parts of London’s construction sector as many as half of workers might be from the EU, there were serious fears about what a leave vote could mean for an industry already facing a skills shortage.

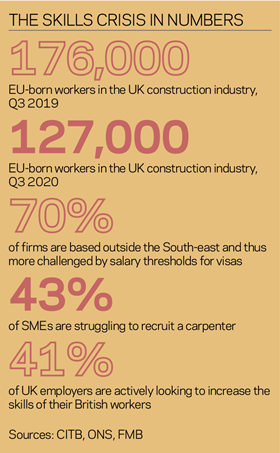

Six years on, there has been a clear change in the number of EU nationals working in UK construction: the Office for National Statistics (ONS) reports a 42% fall between 2017 and the end of 2020. The industry had 176,000 EU-born workers in the third quarter of 2019, but just a year later this had plummeted to 127,000. The exodus of EU-born workers has been greatest in London, where the decline was 30%, from 76,000 to 53,000 in the course of that year.

Construction is struggling to recruit, with vacancies in the industry hitting 48,000 on three occasions in the past year, including for January to March. These are the highest figures since ONS records began 21 years ago.

As part of Building’s Every Person Counts campaign, we spoke to organisations from across the industry to get a feel for whether fears about Brexit from 2016 have been realised, and what firms have been doing in response.

But before looking at how different firms are shaping up, it is worth reminding ourselves briefly of what has changed in the rules around recruitment of EU migrants into the UK.

Points-based system

Since the end of the Brexit transition phase, freedom of movement – which gave nationals of member states the right to work in the UK – no longer applies. Instead, since the beginning of last year, an Australian-style points system has been in place for both EU and non-EU nationals seeking to work in the UK (see “Post-Brexit immigration rules”, below).

This was a key pledge in the Conservative Party’s 2019 general election manifesto. It said it wanted to implement a system “so that we can decide who comes to this country on the basis of the skills they have and the contribution they can make – not where they come from.”

Post-Brexit immigration rules

The primary route for recruitment from the EU since 2021 has been to obtain a visa through the ”skilled worker” route. Under this system, employers pay to sponsor an economic migrant to come to the UK to fill a specific skilled role.

However, to accrue the 70 points required to work in the UK, applicants must be able to speak English, have a certain level of skill and be paid above a certain income level (which varies according to the going rate for different jobs).

Alternatively, larger firms with offices in the EU can use the “intra-company transfer route” to transfer employees over to the UK who have a salary of at least £41,500.

EU-based nationals already working in the UK for at least five years can apply for settled status, or pre-settled status, giving them a route to staying indefinitely.

The points-based system, which was unveiled by home secretary Priti Patel at the end of 2020, came into full effect from 1 January 2021.

The English language requirement, for starters, is proving difficult for some in the construction industry. Laura Darnley, employment lawyer and legal director at Brabners, cites a recent example of a client wanting to bring welders to the UK from overseas. “The workers are skilled, and they meet the skills threshold, but they wouldn’t pass the English language test so they have immediately got a problem,” she says.

Darnley says that firms outside London and the South-east may also struggle to meet the government’s minimum salary thresholds for workers recruited from overseas. To meet the salary threshold, EU nationals must be earning £25,600 a year, £10.10 an hour or the estimated going rate for their role, whichever is higher. The going rates, published for dozens of different occupations in the industry, range from £23,000 for roles such as builder, fencer and maintenance manager, to £24,000 for plasterer, £31,400 for foreman, and £34,900 for construction manager or building services manager. Some 70% of construction firms are based outside London and the South-east, according to the ONS.

The temptation for some employers may be to offer a bigger salary or make a role more senior to enable people to come over, but this is risky, says Darnley. “If there is any evidence that you have created a role or artificially enhanced the skill level in order to fit within the criteria, that would be a compliance breach,” she says.

While the salary and skill level requirements can be problematic, another issue for employers relates to the need for flexible labour to come in and do short-term tasks. Gillian McKearney, senior associate at law firm Fieldfisher, says: “Before Brexit, a lot of our construction clients were bringing in EU nationals for shorter periods at times through the year, maybe to service equipment.”

She says that although there is a business visitor visa that allows one-off visits, sometimes people do not fall into this category, maybe because they are a subcontractor who has a contract with a different firm or needs to make multiple trips. “There’s no obvious visa route for some of these people, so what we tend to do is go to the Home Office on a case-by-base – and the responses are often inconsistent or they don’t come back.”

Darnley also says that the cost and complexity of all this means smaller construction firms “just aren’t engaging” with the immigration system and are making do with domestic labour or simply turning work down.

Cost and complexity

Brian Berry, chief executive of the Federation of Master Builders (FMB), which represents smaller and mid-sized building firms, agrees that many are being “put off recruiting” by the cost and complexity of the system.

“The whole industry is having to adapt to either developing more homegrown talent or negotiating the immigration process with the visa system, and of course for very small companies this becomes a bigger burden because of the resources needed,” he says.

Berry says the salary thresholds can also be problematic for smaller businesses which often want to take on someone at a junior level and train them up. “You need a whole range of labour for a site to function,” he says. He points to figures from the FMB’s most recent state of trade survey of 440 SMEs, which found that 43% were struggling to hire carpenters and 41% struggling to recruit bricklayers.

“This is why we’ve got this situation – why we have a growing skills problem at a time when we have had high demand, particularly for repair, maintenance and improvement work,” he says.

Berry says it often takes three years to train someone up to fill labour gaps, so we are currently in an “awkward gap” where the homegrown talent hasn’t come through yet but the EU labour supply has reduced. He says the government should act to make the system more accessible for smaller companies with fewer resources. “Let’s make it as streamlined and easy as possible for SMEs to recruit,” he says.

> Also Read: Construction must respond quickly to the fast growing number of vacancies

>: Time to open our doors and show next generation what construction has to offer

More should be done to incentivise SMEs to take on apprentices to help with the development of homegrown talent, he says – after all, SMEs train about seven in 10 construction apprentices.

The concern is that the sudden removal of EU labour before homegrown recruits have been brought up to scratch will create problems. Suzannah Nichol, chief executive of Build UK, said last June: “There’s a huge amount of pent-up demand for housebuilding and home and garden improvements over the pandemic. We’ve got a booming industry but a massive skill shortage.”

Berry warns that “we just won’t get things built” unless the longer-term problems are resolved. Asked the extent to which smaller builders are already turning work down because of the EU labour shortages issue, Berry says it is difficult to separate this from other challenges in the market currently, such as materials shortages, but points to an FMB survey last year which showed that 72% of builders have cancelled or delayed work due to skills shortages.

Larger firms are less challenged

While there have been issues for smaller builders at site level, what about larger contractors? Richard Dutton, in-house recruiter at £1.2bn-turnover contractor Wilmott Dixon, says the post‑Brexit rules have made very little difference to the way the business recruits, although he can see why smaller firms in the supply chain may be struggling.

Indeed Dutton says the dropping of the resident labour market test – which required firms recruiting from outside the EU to look to the UK market first – has actually made it easier to hire from non-EU countries. He says: “There are fewer hoops to jump through, in some ways. Before, we had to demonstrate and prove that we couldn’t recruit people in the UK.”

When it comes to EU hires for Wilmott Dixon, Dutton says the salary thresholds are sufficiently low for the roles for which he recruits, although the admin work is a consideration. “Most of the roles that we are recruiting for are white-collar type positions,” he says.

The cost considerations of hiring staff from the EU are very much recognised by Tom Fitzpatrick, head of talent acquisition (UK) at $2.6bn-turnover Amsterdam-based Arcadis. The consultancy firm employs around 5,000 people in the UK. He says that moving a family to Britain can cost “more than £10,000 for relocation that involves a visa”.

Fitzpatrick adds: “There is also the timescale consideration. In a market that moves very quickly, where clients have urgent needs, trying to manage visa processes that are potentially elongated makes things more challenging.”

As a global company, Arcadis has experienced cases where moving people from an office in the EU to the UK has not been straightforward. “There have been individual situations where we have had to look closely at the salary rules in the guidelines,” says Fitzpatrick.

But even if companies become adept at negotiating the labyrinth of visa routes to get people into the UK, this will not be effective unless there are enough EU nationals who actually want to work in UK construction.

Chris Williamson, founding partner at architect Weston Williamson + Partners, says it has become harder to attract interest for roles from EU nationals. He says: “We used to get 20 to 30 applications a week from countries such as Spain, Portugal and Italy – and they have just dried up completely.”

He says this was partly due to the pandemic, with people going home to “be close to their families and then they can’t get back again”, but the issues have persisted. For a practice such as Weston Williamson, where around half of the 120-strong workforce in the past have been from the EU, this is potentially a major problem.

Forging links

“We’ve started looking at other ways of coping with it,” says Williamson. “A lot of us have joined the Royal Institute of the Architects of Ireland [to forge links with potential EU employees]. And then we’re trying to look at whether we can recruit and set up an office in Spain so people can work for us remotely there.

“If people don’t want to come to England or don’t feel welcome in England any more, then we can look at how we can organise ourselves differently and employ the people that we would like to,” he says.

These difficulties in recruiting are despite architecture having been added to the shortage occupation list in the visa system, meaning those seeking to work in the UK in the profession automatically get more points. Karen Mosley, managing director of HLM Architects, said this makes the points-based immigration system easier for recruiting practices, and that she has found the visas to be approved promptly.

Support for Ukraine: slow progress matching displaced people with uk job opportunities

The horrific conflict in eastern Europe has led to 10 million Ukrainians fleeing the country with a further six million displaced within it.

It may not be at the front of all refugees’ minds at the moment – people are more focused on trying to sort out their housing amid the trauma of war – but might there be opportunities for some of these people to work in the construction and architecture sectors? And might construction or architectural firms play a role?

The government has opened two routes for Ukrainians to come to the UK. One is for people joining a UK-based family member, and the other is the Ukraine sponsorship scheme – also known as Homes for Ukraine. Under the latter, sponsors provide accommodation to Ukrainians who can then live, work and study in the UK and access public funds for a three-year period.

Home Office minister Kit Malthouse has said visa applications are now “motoring”, but the most recent figures show that by Wednesday 13 April only 16,400 people had arrived and only 56,500 applications had been approved, from a total of 94,700 applications made.

Fieldfisher’s Gillian McKearney says she has not really been asked about the Homes for Ukraine scheme by her construction clients so far but that other sectors, such as tech, are thinking it would be nice to help out and that “we might get some good talent as well”.

In architecture, the RIBA is using its job platforms to allow chartered practices to advertise roles or apprenticeships for displaced Ukrainians for free. Offers must come with six months’ free accommodation. An advert run by RIBA and Weston Williamson + Partners has had 10 responses from Ukrainians.

Weston Williamson + Partners’ Chris Williamson has called on architectural professionals with spare rooms in their homes to consider offering accommodation to displaced architecture students. He says he has been approached by seven or eight architects offering to help but that there is a need for a “broker” to help architectural students and employers get in touch with each other. The University of East London and the London School of Architecture have shown a willingness to take on students if “we can find the student”, he says.

> Also read: ‘Many problems appear, but we manage them’ – at war and under siege, a Ukrainian manufacturer perseveres

This kind of matching-up of Ukrainian students or workers with offers of both accommodation and work appears to be the key. At the moment companies cannot sponsor under the Homes for Ukraine scheme; it needs to be individuals.

HLM Architects’ Karen Mosley has been using the Hire for Ukraine website to look for people who may be interested. “We’ve actually been interviewing people who have come through there, or people have been contacting us directly, and then if we are in a position to employ we are trying to connect those individuals with people who have registered their homes so that they can name them as an individual to speed up the process.” Mosley says HLM has found one person whom it would like to progress and is trying to find someone in the locality to be the sponsor.

At the moment the vast majority of the refugees are women and children. When the conflict ends, it is likely there will be a period when the men of working age (who were required to stay and fight) will join their families in the UK, bringing in a new tranche of potential recruits.

McKearney says: “If you get a visa, you’ll get it for three years, and then you can work for any company that you want to. So it’s possible that people could come here and there could be more available talent going forward.” She says the Homes for Ukraine scheme does not lead to permanent residency, but “it’s probably possible to apply for other routes from that route”.

However, Mosley says that HLM, like Weston Williamson, is receiving fewer applications from EU nationals than it did previously. This could be due to a perception among prospective employees that the process is too difficult.

She says: “We probably need to do something around this; we’ve been talking about maybe doing a campaign to make it clear it’s maybe not as difficult as it’s perceived – and that we are open to applications and we can help people through the process.”

The idea that EU nationals may no longer want to come here to work in the industry resonates with Fiona Fletcher-Smith, the chief executive of £1bn-turnover L&Q, one of the largest developing housing associations in the country with a 32,000-home development pipeline and its own in-house construction arm. Fletcher-Smith, originally from Ireland, said she felt fairly “unwanted” following the referendum result, despite having lived in the UK for 35 years.

“There is something in that. At the same time as Brexit we saw building booms in places like Poland. So you could go home, be with wider family, still make money. Why would you come to London, particularly, where it’s very expensive to live and you may not feel entirely welcomed?”

She said that before the pandemic around 70% of workers on L&Q’s London sites were from the EU and this has now dropped to about 40%. She thinks, however, that EU numbers are settling down, albeit at a lower rate than previously.

For L&Q, part of the solution is to focus on skills and training, and the firm has taken on 28 apprentices and graduates with another 20 set to be taken on this year.

More broadly there would appear to be a great deal of desire in the industry to train homegrown talent. The Construction Industry Training Board’s annual migration survey in February found 41% of employers are looking to increase the skills of British workers, almost a third (30%) plan to provide more permanent jobs for Britons, a quarter (24%) intend to increase minimum salaries, and 16% are hoping to take on more local apprentices.

Building’s Every Person Counts campaign will be exploring ways to improve pathways into the sector over the coming months as well as showcasing what the industry is doing to develop a skilled workforce. But, as many have noted, all this will take time and in the short term all the indications are that sections of the industry – particularly smaller builders, some specialist contractors and architectural practices – will continue to find it much harder to tap into the vast reservoir of EU labour than was the case just a few years ago.

Every Person Counts

We know the industry has no shortage of suggestions for tackling construction’s skills crisis, from reforming apprenticeships, to offering more flexibility, to increasing diversity, to providing better pathways from education to the workplace. Our Every Person Counts coverage aims to provide a place where debates can play out, views be aired and solutions shared on all these topics.

If you have an employment initiative you want to tell us about email us at newsdesk@building.co.uk with the subject line “Every Person Counts”. You can also contact us via Twitter @BuildingNews and LinkedIn @BuildingMagazine, please use the hashtag #everypersoncounts. We look forward to hearing your employment stories.

You can find all our Every Person Counts coverage in one place on our website.

And if your organisation has a particularly strong record in this area, you could consider entering the Every Person Counts – People Strategy Award at this year’s Building Awards.

No comments yet