The inventors of SmartSlab describe it as an all-in-one, load-bearing, moving-image display slab. It’s also the only system that provides animated displays while retaining all the features associated with external cladding.

The problem first presented itself to professor Tom Barker when he collaborated with architect Zaha Hadid on the Millennium Dome’s Mind Zone. The ambient light of the dome prevented many exhibitors from projecting images onto screens, so simple LED display boards tended to be used. But Barker, then a full-time engineer, and Hadid wanted to show moving images on a floor that visitors would walk on, so a more innovative solution was needed.

Using structural honeycomb to house LEDs protected by a transparent surface, Barker capitalised on what he calls the “convergence between physical construction and digital media”. He succeeded in developing an all-in-one, load-bearing, moving-image display slab.

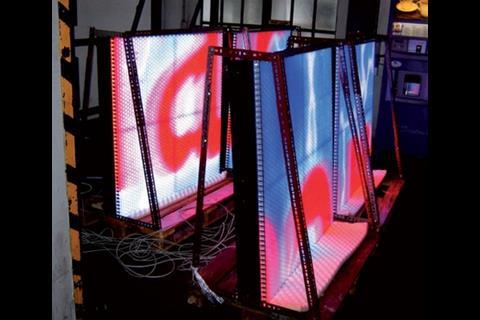

Barker saw another potential use for this technology. Several years down the line, his floor has evolved into SmartSlab, a form of cladding or freestanding structure. According to Barker – who splits his time between the Royal College of Art, Imperial College and the company he set up on the back of his invention – the cladding is the first and so far only system that intrinsically contains lighting components and controls for animated displays while retaining the necessary features associated with external cladding. Unveiled as a prototype at a lighting exhibition in Venice in 2005, SmartSlab’s first commercial application in the UK has just been installed on the street-facing mezzanine of specialist furniture maker Luke Hughes & Company’s showroom in London’s Drury Lane. It has come a long way. So how does it work?

SmartSlab comprises square modules of 600mm sides. For most applications these are bolted together and supplied in any number of four-module “quads”, which can, in turn, be assembled to make larger panels. With a steel frame about 170mm deep, panels can be freestanding up to 5m high.

Each module contains wiring, circuit boards, controls and LEDs, all placed within the steel structure. It is fronted by a 20mm-thick honeycomb and facia structure made from polycarbonate, which gives the panels a horizontal load capacity of 3kN/m2.

As a byproduct of oil, polycarbonate can also be made from bio-plastics and is recyclable. It contains no toxic materials and, to illustrate its strength, Barker says that polycarbonate sheets have been used to shield US president George Bush from bullets.

There are three basic structural options.

The panels can stand alone as a flat or 3D structure. They can be erected with 650mm of access space away from existing or new walls. Most innovatively, they can be attached like a rainscreen using simple slotted metal channels and fitted as the final skin of a standard wall, providing an alternative form of cladding.

With this final option, access to carry out maintenance can be gained by disengaging the electromagnetic bolts that hold the panels in place. These are locked unless switched on.

The outer material is tough enough to withstand most vandalism and graffiti or dirt can be easily washed off. Barker says it performs at least as well as standard double-glazing and passes all building regulations.

It also offers the added advantage of better acoustic performance that comes with increased material stiffness. Placed 3mm from each other, the gaps between the panels are filled with silicon beads and a silicon seal, which provides waterproofing and caters for thermal expansion.

The digital media technology is as impressive as the structure. Moving image data is sent from a computer, Bluetooth or other device to an array of modules and can be controlled remotely. Any number can be used and the system is calibrated accordingly. One computer is able to cope with up to 400m2 of screen area.

The hexagons of the honeycomb each contain one LED. Three hexagon sizes are available. Small hexagons and large panel areas give the best definition. LEDs have

very long lives and, partly because they do not need to illuminate anything, their energy consumption is relatively low.

Given the usual brightness and colour reductions associated with producing moving images, Barker estimates that the average 600mm square module will use about 120W. It would use 600W if on at full intensity.

Despite these attributes, LEDs, like other lights, produce a lot of heat. Internal lights affect indoor temperatures, to which air-conditioning systems respond. The waste heat from external lighting systems, on the other hand, could easily be lost. To overcome this, SmartSlab has a built-in heat recovery system. When dormant, the cladding reverts to what Barker calls “Norman Foster grey”, an uncontroversial colour achieved by using a filter in the polycarbonate facia.

So will enough people want to buy it? Iain Ruxton, design associate for lighting architect Speirs & Major, can see the advantages and says he knows of no other system that integrates interactive display boards with cladding. He recalls being impressed by the prototype when he saw it in Venice and points out the obvious cost-cutting benefits of combining a display board with a cladding system. “Loads of projects could need this sort of thing,” he says.

Barbara Anderson, executive chair of SmartSlab, handles the commercial side of the operation and is bullish about the product’s prospects. Her company’s impressive financial performance supports this: despite being a small company with a handful of employees, last year’s turnover was £1m with a £360,000 profit.

Much of this revenue comes from third-party companies that buy stock to sell on. Manufacturing and distribution rights for most of the world have also been bought by Targetti Sankey, a large Italian lighting specialist. Anderson sees sales increasing strongly and direct competition coming only on a “per project basis” from bespoke outfitters. She envisages business coming from architecture and design firms, retail and branding projects (retrofitting and new build), sport and leisure, and entertainment.

There may also be a market for local authorities that want to find new ways of circulating information to their residents. (Perhaps giving local authorities a percentage of SmartSlab air time could help smoothe the planning process.)

So SmartSlab is glowing. But where might it all end? Barker says the “future of interaction will be through mobile phones”. And he’s not just referring to how SmartSlab is programmed; he’s alluding to as-yet-illegal technologies that could allow advertisers to detect passers-by from their mobile phone signals and alter advertising displays according to a database of their interests.

Isn’t that a little Orwellian? “Yes!” says Barker with an impish grin – though thankfully he’s unlikely to be endorsing such a sinister application for SmartSlab.

Topics

Specifier 06 July 2007

Cladding

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

Slab happy

- 14

- 15

No comments yet