Timber is well suited to the harsh environment of an indoor swimming pool, but at Longwell Green the finish also decided the way the building was constructed, as Stephen Kennett discovered

The Longwell Green leisure centre doesn’t look much like your average council swimming pool. Set amid McDonald’s drive-throughs and cinema complexes six miles from the centre of Bristol, it is randomly clad in oak planks of varying thicknesses and lengths. But it was the timber inside that had the biggest influence on the building’s construction.

Architect Feilden Clegg Bradley wanted a clean, seamless timber ceiling with a flat soffit and as few joints as possible. With this in mind, they earmarked Finnforest’s Kerto laminated veneer lumber, which comes in 2.4m wide sheets up to 26m in length, for the ceiling finish.

Timber lends itself well to the humid and corrosive environment of a swimming pool. Stephen Melville, director of structural engineers Ramboll Whitbybird says: “If you use any steel you have to galvanize it heavily, and it’s impossible to make reinforced concrete without microscopic cracks, so if you use it you’ll end up with rust stains from the reinforcement bar, which won’t kill your building but will look awful”.

The problem at Longwell, according to Melville, was that although Kerto gave a seamless and resilient finish, the size of the sheets meant they were virtually impossible to manoeuvre on site. “We were going to have to have some form of prefabrication,” he says.

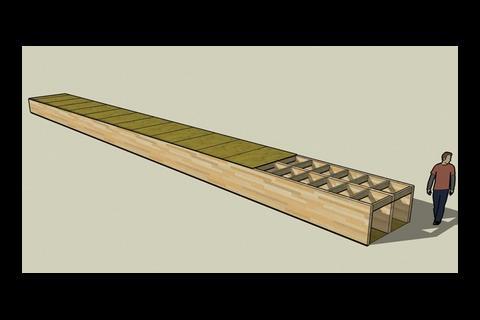

It was finally decided to design a prefabricated timber cassette, which would span the entire 18.5m width of the six-lane pool hall. This comprised tapering glulam beams with a plywood top deck and a timber sheet for the bottom.

Ramboll Whitbybird had used timber on a number of swimming pool schemes before, but never when building off site.

There were two main challenges when it came to constructing such large prefabricated sections. The first was transportation – because the pieces had to be trucked down from South Yorkshire, there was a limit on how long they could be.

The second was treating the beams with preservative. Simply painting it on was not an option, particularly as once the structure was fixed in place it would be largely inaccessible for the lifetime of the building. Instead, each completed cassette needed to be lowered into a pressurised tank that forced the preservative into the timber.

“There are limits to the size and shape you can treat, because they won’t always fit in the tank,” says Nicholas Porter, project engineer with Ramboll Whitbybird. This meant that the team had to design sections that were small enough to fit in the tank.

Putting it together

On the roof, the 1.8m-wide cassettes butt up against one another and are bolted together.

Another vital consideration was that all the fixings in the structure should be resistant to corrosion. “People think stainless steel doesn’t corrode, but it does if you specify the wrong type of stainless steel,” says Porter. The team spent a lot of time researching the connections and eventually settled on screws with a high nickel and molybdenum content, which would counteract the unusual conditions in the hall.

For the upper deck of the cassettes, type 636-2 plywood is used, which resists humidity and swelling. However, the designers were worried that rain during the construction might cause the wood structure to swell and move. “You have to be very careful the sheeting material doesn’t get wet during construction or it’s in danger of swelling and causing problems,” says Melville. “We had to make sure the contractor was very aware of that.”

To reduce the effects of moisture, and to defend against a sudden downpour, temporary waterproofing was erected. The sequencing of roof coverings was also thought through carefully to ensure the roof was watertight as quickly as possible. As soon as the cassettes were fixed in position on site, a vapour barrier went down onto the plywood deck, followed by insulation and a single-ply roofing membrane.

The finished building

Overall, the team is pretty satisfied with the result. A neat feature of the roof is that its fall is built in without needing to install columns of different heights or to pack up the final layer. The cassettes taper from 1,000mm to 600mm, which means the fall and the flat soffit are provided in one unit.

So what did the team learn from the project? Melville says one of the most important lessons was to involve as many trade bodies and specialists as possible as early as possible. “Not only was if difficult to find the right tank to pressure-impregnate the panels, but there was the added factor of what colour the timber would go – there were scare stories about timber that ended up blue or bright yellow. Another issue was what size of prefabricated sections could be transported.”

Melville says talking to specialists in these areas before manufacturing started was the key to the project’s successful outcome.

Now, timber is being considered for a number of schemes the firm is working on. Melville says it is no longer simply a case of going for concrete or steel. “We go for what works best”. And in this case, that was timber.

If you use reinforced concrete you’ll end up with rust stains, which won’t kill your building but will look awful

Stephen Melville, Ramboll Whitbybird

‘You love it or hate it’

Andy Couling, a partner in Feilden Clegg Bradley, explains the role timber played in the design of Longwell Green.

What was your vision for the pool hall?

We wanted to create a simple, honest interior. The budget for Longwell Green was tight – £5.3m in total – but we wanted to achieve something that had quality to it, and one way to do that was to simplify the form so we didn’t spend money on complicated geometry but on fabric instead.

You’ve used Kerto before at the Formby swimming pool in Lancashire. What’s different about this project?

The Formby project alerted us to the limits of Kerto. Primarily it is used by architects as a joinery material, and it struggles. We got there in the end with Formby but there was quite a bit of site damage to the timber and effort required to get the look good enough. It’s not easy to repair because it is made out of veneers – you can’t just sand it or cut it up as you could with glulam. Longwell Green was a concerted effort to use the material in a much more industrial way.

How did you do this?

We thought through the prototype roof cassettes carefully so that they were easy to make in a factory and could be transported by truck.

Did you consider any other finishes?

We could probably have got a similar effect by using plywood but it wouldn’t have been quite so clean, it would have been a compromise. Part of the process of coming to this solution was that we could do it with one sheet, which gave us this continuous smooth surface.

Were you or the client concerned about using timber in such a harsh environment?

Surprisingly, timber does quite well in pool halls.

It does better than steel in many ways, as the chlorine doesn’t attack it. The humidity is a bit of an issue and the main concern was that it didn’t penetrate into the roof cassettes. The client was quite keen on the use of timber from a sustainability perspective.

How have you used timber in the rest of the building?

As well as the pool hall, Kerto is also used in the fitness suite and birch ply has been used on the underside of the ceilings in the changing rooms.

It’s also used for the external cladding. The site is on an out-of-town leisure park and is surrounded by huge sheds. We were quite keen to do something that was consciously different, but it still had to be a fairly simple shed because of the budget. It is also deliberately quite crude, to give it a strong form to stand out in that environment. We used oak – the original intention was to do it in softwood with a black stain which would have been a stronger architectural statement, but the client was concerned that it might be a bit too strong.

Why did you go for such a random finish?

The idea of using different thicknesses of cladding timbers was very deliberate. We wanted to accentuate the way that different degrees of exposure define the way the timber weathers. The one bonus that I hadn’t really considered at the time of designing it is that on a flat, grey day in the rain, the more prominent timbers become wet and dark and it becomes a stripy building rather than flat and bland.To achieve the random finish, we specified a percentage of different thicknesses and lengths and then let the contractor get on with it, which meant it was truly random. And also the contractors weren’t having to constantly refer to drawings. It’s one of those buildings you either love or hate. I’m happy with the way it looks.

Specifier 03 October 2008

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

The wet room

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

No comments yet